Seoul Type Housing Voucher Program

Overview

Background

| <Figure 1> Housing Voucher's Effect on Short-Term and Medium-and Long-Term Markets | <Figure 2> Public Rental Housing's Effect on Short-Term and Medium-and-Long-Term Markets | |

.JPG)

.JPG)

In the Republic of Korea, the fundamental human right of the protection of one-day life zone was legalized through the Livelihood Protection Act in 1961. Afterwards, this law was improved partially through several amendments. However, no further steps have been taken, and it has simply remained as a form of residual/beneficent livelihood security that shifts the responsibility for poverty on to the individuals concerned.

Responsibility has been attributed to individuals as well for housing problems of poor people. Since the 1980s, the suicide rate among low-income people who were kicked out into the streets due to the rapid increase of housing prices and rents has become a serious social issue. In response, the SMG clearly could not leave the housing problems of the poor at the mercy of market mechanisms. Under these circumstances, the public rental housing program was launched in earnest from 1989 as a way of alleviating social discontent and realizing social integration.

As for housing expense support, the Secured Loan Rental Housing Program for low-income people was introduced in 1990, followed by the Secured Loan Rental Housing Program for workers and common people in 1994.

Then, with the social security system not yet matured, the financial crisis (IMF bailout loan) occurred in 1998, causing a severe social problem of mass unemployment. Accordingly, the National Basic Livelihood Security Act was put into effect from 2000 in order to overcome the limits of the "Livelihood Protection Act" and guarantee that all people living with less than the minimum cost of living should reach the minimum standard of living and be able to support themselves. In the early stage of this system, those who were entitled to benefit from the National Basic Livelihood Security Act received living allowances including housing expenses. Setting aside the existing living allowances, a new system for housing allowances was established so that the recipients could receive appropriate allowances according to their actual housing conditions, and thus live in better residential environments. However, the low level of allowances fell short of providing substantial assistance to poor people and also failed to consider their regional and household circumstances and characteristics. Even worse, there was no clear division between living allowances and housing allowances. So, in many cases, recipients could not afford to move into better houses by using their housing allowances.

Before the IMF financial crisis, the rent of private rental houses continued to rise, imposing a heavy financial burden not only on the poor but also on most low-income tenants. Furthermore, unlike other regions, it was not easy to secure new housing sites in Seoul; and, due to its relatively high land prices, it was also difficult to supply more houses there. Under these circumstances, rents rose drastically while household incomes dropped sharply in the wake of the IMF bailout loan. Thus, those in the low-income group could not receive any help while suffering from an increasingly heavy burden of housing expenses.

Since the 2000s, the existing lease system has also undergone a significant change in such a way that the deposit-based lease system decreased and the monthly rent system increased. What is worse, the problem affected not only the recipients of national basic livelihood guarantees, but also low-income people. They could not benefit from government assistance even if they were experiencing financial difficulties and felt heavily burdened by their monthly rent.

Therefore, the SMG launched a monthly rent aid system that supports housing expenses for low-income tenants by using only its own budget from 2002. Its financial resources came from the housing fund (currently named the "housing assistance account of the social welfare fund") established by the SMG itself. However, the Seoul Type Housing Voucher takes the form of lump-sum grants of a small amount of money due to limited financial resources and the difficulty in figuring out actual household incomes. Therefore, it can be considered a housing subsidy system, with greater emphasis on income support rather than the distribution of housing vouchers.

Currently, the housing subsidy system has not yet been implemented nationwide in the Republic of Korea. As the national basic livelihood security system was transformed into the individual benefit mode in 2014, the housing voucher system will take effect from the following year after a pilot project.

Contents

Eligible Households and Amount of Subsidy

When the "monthly rent aid system" began in 2002, its assistance went to members of the social vulnerable class among households whose incomes represented less than 120% of the income criteria for selecting recipients under the "National Basic Living Security Act" (less than the bottom 15% of the income bracket), and those who lived in private rental houses on a monthly basis; but it excluded those who received housing allowances under the "National Basic Living Security Act." The subsidy was provided on a fixed amount basis according to the number of household members; 33,000 won for one- or two-person households, 42,000 won for three- or four-person households, and 55,000 won for households with five or more persons.

Then, in 2008, the subsidy was increased to 43,000 won for one- or two-person households, 52,000 won for three- or four-person households, and 65,000 won for households with five or more persons. The criteria for rental rates were established in 2010, excluding those whose rent-converted security deposit value (= security deposit + monthly rent × 50) exceeded a fixed amount. In other words, the subsidy for rent was provided only to households whose rent-converted security deposit value was less than 60 million or 70 million won.

From November 2010, the existing rent subsidy was renamed as the "general voucher," while a "specific voucher" and a "temporary housing voucher (coupon)" were newly established for conversion to the Seoul type housing voucher system. Although it used the word "voucher," it actually provided a subsidy in the form of cash without using a voucher or coupon. In other words, it took the form of a housing allowance system under the name of "housing voucher." This new Seoul type housing voucher system was reformed to support the housing expenses of even households whose incomes were higher than the existing income cutoff with a specific voucher. The temporary housing voucher program allowed free residence in public housing for three to six months, and targeted tenants who faced a housing crisis due to their rental housing being put up for auction or exhaustion of their security deposit.

In 2013, the SMG started to integrate the general voucher and the specific voucher into one and abolished the temporary housing voucher. In other words, the current Seoul type housing voucher has been simplified to target only those households whose incomes represent the bottom 20% of the income bracket (within 150% of the criteria for selecting beneficiaries under the "National Basic Living Security Act") while residing in private rental houses on a monthly basis. However, it excludes recipients under the "National Basic Living Security Act" and households whose rent-converted security deposit value exceeds 70 million won. The subsidy is determined according to the number of members of a household, as follows: 43,000 won for one-person households, 47,500 won for two-person households, 52,000 won for three-person households, 58,500 won for four-person households, 65,000 won for five-person households and 72,500 won for households with six persons or more.

Application of Rent Subsidy and Payment Method

To benefit from the rent subsidy, tenants must complete an application only upon concluding a lease agreement. At that time, the required documents should include a copy of the lease agreement, a document proving the applicant’s eligibility for the subsidy, and a copy of their bank deposit book.

In its early stage, this system dispersed money to those who were eligible for a rent subsidy on a monthly basis by depositing the money into their bank accounts. From 2010, however, the system was reformed to deposit money directly into the lessor's account; and the money could be sent to the tenant's account for inevitable reasons only. In fact, more than 90% of the housing voucher beneficiaries have received the subsidy through bank accounts. If their monetary claims are placed under attachment due to defaults on their obligations, the subsidy could go to spouses, linear relations, or collateral relatives removed by three degrees of less, instead.

Payment Procedure

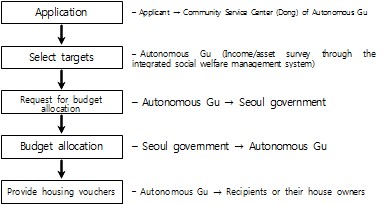

Until 2009, subsidy recipients were selected after due deliberation by basic security committees established in autonomous regions (Gu). In 2010, however, its selection procedure was reformed in order to select recipients based on an income survey conducted through the integrated social welfare management system (Haengbok-eUm). To receive the housing voucher, recipients must complete an application directly at their community service center (Dong). The autonomous Gu now determines their subsidy recipients through income surveys and requests budget allocations in order to grant subsidies to house owners or subsidy beneficiaries.

<Figure 4> Housing Voucher Supporting Procedure

Financial Resources for Housing Vouchers

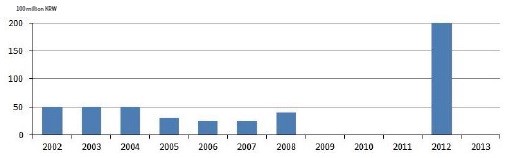

Currently, the financing source for the Seoul type housing voucher is the "housing assistance account" of the Seoul Social Welfare Fund. Its main resources come from contributions from the general account budget of the SMG, for which 47 billion won was raised from 2002 to 2013. The SMG contributed 5 billion won to that account continuously between 2002 and 2004. However, it decreased its deposits to 3 billion won in 2005, 2.5 billion won in 2006 and 2007, and 4 billion won in 2008, and it even failed to make any contributions from 2009 to 2011. However, with the election of a new Seoul mayor, 20 billion won was deposited into the housing assistance account from the general account budget in 2012.

<Figure 5> Contributions from the SMG’s Budget

Subsidy Results

The number of households supported by the Seoul-type housing vouchers has increased continuously. For example, only 963 households could benefit from this system on an average monthly basis when the system was launched in 2002. Thereafter, the number increased by around 500 each year from 2004 to 2007.

The number decreased in 2008, but increased again to 4,982 in 2010, i.e. 1,600 more than the previous year. As the extension of the Seoul type housing voucher was included in the "Seoul Citizens' Welfare Standards" from 2012, the number of households who received support increased by more than 2,000 from the previous year, and went on to reach 10,094 per month on average in 2013.

The annual grant also continued to increase dramatically - from 340 million won in 2002 to 5.56 billion won in 2013. The total amount of the subsidy was 23.24 billion won from 2002 to 2013, with the annual grant per household rising by as much as 200,000 won, from 352,000 won in 2002 to 551,000 won in 2013.

<Table 1> Seoul-Type Housing Voucher (Monthly Rent Subsidy) Assistance Results by Years

|

Classification |

Monthly Average Households Supported |

Total Annual Subsidy (1 million KRW) |

Annual Subsidy by Households (10,000 KRW) |

|

2002 |

963 |

338.8 |

35.2 |

|

2003 |

1,040 |

453.4 |

43.6 |

|

2004 |

1,537 |

679.5 |

44.2 |

|

2005 |

2,231 |

976.4 |

43.8 |

|

2006 |

2,782 |

1,268.2 |

45.6 |

|

2007 |

3,255 |

1,497.1 |

46.0 |

|

2008 |

3,175 |

1,461.6 |

46.0 |

|

2009 |

3,382 |

1,992.0 |

58.9 |

|

2010 |

4,982 |

2,611.5 |

52.4 |

|

2011 |

5,540 |

3,102.9 |

56.0 |

|

2012 |

7,685 |

3,299.0 |

42.9 |

|

2013 |

10,094 |

5,562.0 |

55.1 |

|

Total |

46,666 |

23,242.4 |

49.8 |

Tasks in Promotional Process

Therefore, it could decrease the rent of private rental houses if there is a lack of housing stock or if there are many people living in poor houses. It is also necessary to extend the supply of public rental houses, as this has a significant effect on the beneficiaries’ residential stability and benefits. In many advanced countries, the public rental housing program was implemented first, followed by the housing subsidy program. Most of them gained experience of supplying public rental houses from the 1940s and ’50s, while reducing the supply of public rental houses and extending the housing subsidy system after undergoing a financial crisis in the 1970s. However, they all had a large stock of public rental houses, so, despite their reduction of supply, they still owned a sufficient level of housing inventory.

Recently, however, the argument has been made that the cost efficiency of the housing subsidy system may be lower than that of the public rental housing program in the long term, especially in countries that have run the housing subsidy system for more than twenty years. As a result, to guarantee the residential stability of low-income rent households, it is necessary to preferentially secure a sufficient stock of public rental houses, and then to utilize the housing subsidy system at a later time as a desirable complementary policy.

Results and Suggestions

<Table 2> Satisfaction with Seoul Type Housing Voucher

| Satisfaction with the Housing Voucher System | Very satisfactory | Somewhat satisfactory | Somewhat unsatisfactory | Very unsatisfactory | No idea/no response |

| 11.0% | 51.0% | 34.6% | 2.6% | 0.8% | |

| Contribution to Reduction of Housing Expenses | Very helpful | Somewhat helpful | Somewhat unhelpful | Not very helpful | No idea/no response |

| 6.4% | 66.8% | 21.4% | 5.2% | 0.2% | |

| Source: The Opinion, 2012, "Report on the Survey on Seoul Citizens' Satisfaction with Administrative Housing Policies." | |||||

From now on, the level of subsidies must be increased by 20-30% of reference or actual rents so that the housing subsidy system can lead to actual residential stability or upward housing mobility. In this case, we need to create a new system capable of figuring out low-income tenants’ incomes and rents accurately. Like the US’s Housing Choice Voucher and the UK’s Local Housing Allowance, we need to increase the amount of subsidies considerably enough to link them with the recipients’ incomes and rents. However, this sort of program, which entails giving cash directly to the recipients, requires not only a large budget but also public consensus.

References

The Opinion, 2012, "Report on "Seoul Citizens' Satisfaction Survey on Administrative Housing Policies"

Park Eun-cheol, 2011, "Operational Improvement and Development Plan for Seoul Type Housing Voucher," Seoul Development Institute

Park Eun-cheol, 2013, "Introduction of Housing Subsidy Program at Issue," "3rd Housing Welfare Conference" Book, the Housing Welfare Conference Organizing Committee

Park Eun-cheol and Bong In-sik et al., "Housing Subsidy System Cases and Issues," the Korea Planning Association, "Urban Information," No. 381

Seoul Metropolitan City, 2013, "Status of Seoul Type Housing Voucher System"

Seoul Metropolitan City, 2014, "East Asian Housing Market and Housing Policy Case Study"

Jeong Eui-cheol, 1997, "Rent Aid System Introduction for Low-Income Citizens in Seoul," the Seoul Development Institute