Landscape Management Policy for Better Seoul

Background

Damage to Landscapes near Mountains, Rivers and Historic and Cultural Properties Caused by Reckless Development in the 1970s and 1980s

Housing Supply-Centered Policy in Development & Growth Periods

Seoul underwent dramatic changes due to economic development in the 1960s, and started to focus on supplying houses in the 1970-80s. Based on the "Housing Construction Promotion Act" enacted in 1972, houses were supplied on a massive scale. This was followed by the enactment of the "Housing Site Development Promotion Act," which was designed to effectively promote large-scale housing site development in the 1980s. Thereafter, a number of large apartment complexes were built across Seoul. In particular, the hilly areas overcrowded with dilapidated houses were released from the restrictions which were imposed on scenic areas, so that apartments could be built in those areas on a grand scale. High-rise, high-density apartment developments grew more fiercely due to the deregulation of building controls, including an increase in both the floor area ratio and the building coverage ratio of apartments, and a lower pitch of buildings according to the housing construction promotion plan issued in 1985. However, the construction of high-rise, high-density apartments around mountains and rivers began to damage the urban landscape as a whole, producing an overwhelmingly standardized view.

Downtown Redevelopment Policy for Modernization of Urban Functions

The "Urban Redevelopment Act" was enacted in 1976, followed by the establishment of the first "Basic Plan for Urban Redevelopment" in 1978. Then, the SMG complemented this basic plan and implemented active urban development by relaxing the restrictions imposed on the floor area ratio and the building coverage ratio for residential complex development. This urban redevelopment policy brought about the modernization of urban existence, such as the construction of modern-style buildings, the improvement of road networks, and the expansion of parks and parking lots. However, it fell short of considering the historic and cultural characteristics of downtown areas, which in turn led to many cultural heritages and urban structures across the city being destroyed by large-scale urban development.

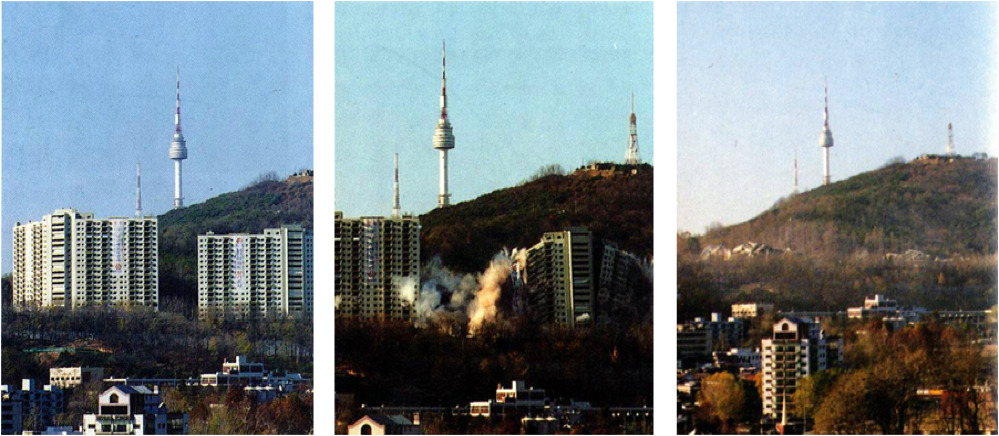

Natural Landscape Management with the Removal of "Namsan Oein Apartment" as the Momentum

In 1991, the "Basic Plan for the Recovery of Namsan Mountain" proposed to transfer or remove ten encroaching facilities including the U.S. army facilities and the capital defense command (CDC), and to transform the territory into a park. Subsequently, the Namsan Oein apartments were torn down in 1994 through measures taken by the "Namsan Recovery Committee." The apartment concerned was originally built for the purpose of accommodating many of the foreigners who had been invited to Korea to pass on advanced technology when the economic development plan of the late 1960s was in full swing. It stood high at the foot of Namsan Mountain, so it could be seen easily from everywhere in the city, blocking out the original scenic view of the mountain. At that time, its demolition was aired live on TV and served as an opportunity to raise public awareness about the value of the city’s landscape.

<Figure 1> Demolition of the Namsan Oein Apartments (1994)

Implementation of the Scenic Conservation Act with the Focus on Inducement and Support

In the early 1990s, the SMG and academic circles began to recognize the need to manage the urban landscape, and established several plans for limiting the height and scale of buildings. By doing so, they intended to secure the scenic views of mountains and rivers, which corresponded to the landscape frameworks. However, the regulation-oriented landscape plan was non-statutory, without an applicable law, thus limiting the execution of the plans based on related laws. Furthermore, the urban landscape is generally formed by measures set forth in urban plans of which the scope includes buildings, parks, green areas and the like, all of which are managed and operated according to individual laws (such as the Land Planning and Utilization Act, Building Act, and Act on Urban Parks, Greenbelts, etc.). Therefore, for the realization of landscape management, there was a growing need to implement an applicable law that would cover all of the landscape targets to be managed. Accordingly, the Scenic Conservation Act was enacted in 2007 to lay the institutional groundwork for the preservation, management and formation of landscape resources by, for example, establishing landscape plans, executing landscape projects, and concluding a landscape agreement with land owners along with their support. The SMG established its statutory landscape plans for the first time as a local government based on the landscape ordinance in 2008 and the Scenic Conservation Act in 2009. Then, it mapped out specific landscape plans for each type of landscape: natural green spaces, waterside areas, history and culture zones, nightlife areas, and streets.

History

1st Period: Start of Protection and Management of Damaged Urban Landscapes

Seoul is a city with its own unique urban identity that has been formed by the landscape framework, including its four inner mountains (Bugaksan, Naksan, Namsan and Inwangsan), four outer mountains (Bukhansan, Gwanaksan, Yongmasan/Achasan and Deokyangsan), the Han River, and four streams (Hongjecheon, Jungrangcheon, Anyangcheon and Tancheon), as well as downtown palaces, the ancient Hanyang City Wall, traditional Korean-style houses, and diverse historic cultural properties. Therefore, when demand arose for greater efforts to manage damaged urban landscapes and protect Seoul's own unique landscapes in the early 1990s, concerted efforts led by related academic societies and research institutes were made to secure the scenic views of natural landscapes. At the same time, relevant laws were enacted and amended to lay the institutional groundwork for the realization of landscape management. Although the city’s historic and cultural landscapes constituted a key element in forming the identity of Seoul along with its natural landscapes, the SMG was not very interested in protecting and managing unlisted historic and cultural resources, preferring to focus only on listed historic and cultural properties.

Securing Scenic Views of Natural Landscape Resources such as Mountains and Rivers

○ In many studies, it was suggested that a view should be selected based on theoretical backgrounds and that how a view is secured between buildings must be regulated, so that people could view the landscape above the fifth to seventh ridges of mountains. To realize landscape management, they also suggested the designation of scenic districts and the application of deliberation standards, etc. However, in the case of designating scenic districts, which might lead to an infringement of property rights, it is necessary to first win public consensus. When it comes to the height of buildings, which were defined by the existing system used by districts and setback regulations, there is a limit to regulating the height based on only landscape plans, which have no recourse to an applicable law. As such, the methods of securing a view suggested in many studies have not yet been executed.

Protection and Formation of Historic and Cultural Landscapes through District Unit Planning

○ Historic and cultural landscape resources such as ancient palaces and the Hanyang City Wall constitute a key element in forming the identity of Seoul, along with its natural landscape formed of mountains and rivers. Nevertheless, there have been virtually no studies conducted with the aim of protecting and managing such landscapes to date. Listed historic and cultural properties have been protected by the designation as a cultural heritage protection area, elevation control, etc., but there is still a limit to forming the landscape of adjacent areas in consideration of the corresponding cultural properties. Most of the unlisted historic and cultural landscape resources were also excluded from protection and management.

○ There was growing demand to protect and manage the historic and cultural resources and landscapes which had been damaged or lost during the period of rapid urban development. The SMG started to map out its district unit plans, centering on the city’s characteristic centers of historic and cultural resources, such as Bukchon, Insa-dong and Myeong-dong. The purpose of the district unit planning of these characteristic centers was not only to protect and manage historic and cultural landscapes, but also to contribute to their maintenance through detailed planning.

Laying the Institutional Groundwork for Landscape Management

○ Seoul Architectural Committee Rules on Apartment House Design Review

- At a time when the reconstruction of large-scale apartments was proceeding apace, the SMG had no means to conduct city management. Then, it temporarily succeeded in enacting the "Seoul Architectural Committee Rules on Apartment House Design Review" in 1999. These rules on apartment house design review were classified into indexical deliberation criteria and derivative deliberation criteria. The former includes the elevation area, elevation blockage ratio, height limit on hills, outdoor living space, sidewalk ratio and roadway ratio. The latter includes the complex formation and layout plan, cutting/banking ratio, land deformation ratio, building type and number of stories, circulation planning in complex, structural plan, landscape plan, existing tree preservation, color plan and underground excavation. The rules on apartment house review were enacted according to the "Land Planning and Utilization Act" in order to manage the scale of apartment houses, including the local floor area ratio, number of stories, maximum height, and building layout and type. However, it was abolished in 2008 with the enactment of the "Apartment House Architectural Design Review Standards," which aimed to secure a diversity of designs and form high-quality residential environments.

○ Landscape Areas

- As the "Urban Planning Act" was completely revised in 2000, the SMG subdivided landscape areas into natural landscapes, visual landscapes, waterfront landscapes, cultural heritage landscapes, street landscapes, and scenic landscapes through an amendment to the urban planning ordinances. On that basis, of the twenty-four scenic areas designated according to the Joseon Street Planning Act in 1941, twenty were changed into natural landscape areas and four were changed into visual landscape areas. Then, according to the "Land Planning and Utilization Act" enacted in 2003, which allowed the designation of natural landscape, waterfront landscape and street landscape areas, the SMG permitted the designation of visual landscape, cultural heritage landscape and scenic landscape areas through a revision of the urban planning ordinances.

- However, it was difficult to designate additional new landscape areas owing to the fact that people living in the existing natural landscape areas continued to raise civil complaints against the designations as it infringed on their property rights. Accordingly, the city council decided to exempt several districts from designation because they had neither been designated before nor produced any actual benefits from separate regulations. Therefore, the scenic landscape and cultural heritage landscape areas were deleted in 2009. At present, the SMG is allowed to designate natural landscape, waterfront landscape and street landscape areas according to the Land Planning and Utilization Act and to designate visual landscape areas under the urban planning ordinance. As of 2013, the total size of landscape areas amounted to 13.1km2, with only natural and visual landscape areas designated.

○ Average Number of Stories

- Due to compulsory rental housing reconstruction in 2006, the floor area ratio was increased by 10-30%, making a change inevitable in the height limit of buildings in type II general residential areas, whose floor area ratio and number of stories were limited to 200% and 12-15, respectively. Furthermore, due to the previous limit on the maximum number of stories, the city landscape of housing areas began to look too uniform and standardized. In addition, a continuous stream of civil complaints was raised regarding the poor residential environment caused by the difference in building heights from other nearby areas with lower height limits. Against this background, to create a variable skyline and a better urban landscape, the SMG set the average number of stories (the number of stories obtained by dividing the ground area of apartments by a reference area, under Clause 2, Article 28 of the Seoul Urban Planning Ordinance) for the first time as a local government through a revision of the Seoul Urban Planning Ordinance.

- In the case of building apartments in the District Unit Planning Areas and Renewal Areas, the average number of stories was alleviated and raised to 11 for type II general residential areas (previously 7 stories or lower) and to 16 for type II general residential areas (previously 12 stories or lower) in consideration of their contribution to the public interest through land donations for public sites and their potential to improve the landscapes of adjacent areas.

- Then, in 2009, there was an attempt to compensate the issue of hills, which formed a uniform and standardized landscape view due to the application of an absolute number of stories without considering the local geographical characteristics. Therefore, the type II general residential areas were divided into hilly areas and flatland areas, to which differential criteria for alleviating the limit on the number of stories were then applied after taking the regional characteristics into account, while maintaining the framework of the subdivision (7 and 12 stories) of type II general residential areas. Conversely, districts in need of landscape management were excluded from the alleviation of the limit on the number of floors. In this way, the government set a strict restriction on the simple upgrading of building stories in specific use districts. However, if an architectural plan (special landscape design, etc.) for hills was made through a design competition or if there was consultation with the committee in advance, the government could apply a separate criterion to that case within a scope of 18 stories on average, thus enabling the architectural planning of various designs in practice. Meanwhile, in the case of building apartments with a structure capable of easy remodeling, the average number of stories could be relaxed to within 20% of the corresponding standard. In so doing, the government had taken measures to prevent reckless reconstruction from causing any environmental damage and waste of resources.

<Table 3> Improvement Proposal for Average Number of Stories (2009)

| Use Districts | Classification | Reference Number of Stories | Maximum Number of Stories | Infrastructure Burden Ratio |

| Type II General Residential Area (7 stories or less) |

Hill | 10 stories or less on average | 13 stories or less on average | 5% |

| Flatland | 13 stories or less on average | 10% | ||

| Type II General Residential Area (12 stories or less) |

Hill | 15 stories or less on average | 18 stories or less on average | 5% |

| Flatland | 18 stories or less on average | 10% |

- By considering the ordinance on the limited number of building stories in type II general residential areas through the revision of the Land Planning and Utilization Act in 2012, the SMG maintained the limit on the number of stories in type II general residential areas (7 stories or lower), but abolished the limit on type II general residential areas (12 stories or lower). In the case of building apartments, the government tried to suppress the construction of reckless high-density developments by setting a limit on the number of stories through the committee's deliberation for the purpose of managing the landscapes and protecting residential environments. Therefore, in the case of building apartments in type II general residential areas, the number of stories must be limited to 7 on average. However, such a number could be relaxed to 13 or lower on average, as long as some of the land is donated for public facilities.

2nd Period: Landscape Planning based on the Induction/Support-Centered Scenic Conservation Act

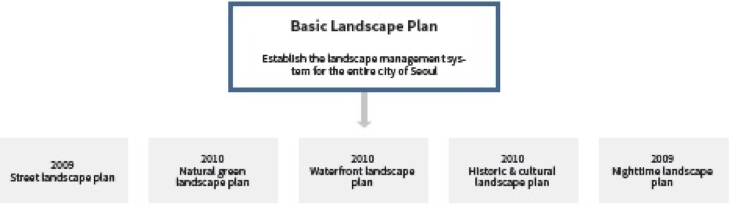

The SMG established its basic landscape plan in 2009 based on the Scenic Conservation Act enacted in 2007, and mapped out a specific landscape plan for each type of landscape in the following year. The Seoul Basic Landscape Plan was designed to lay the framework for landscape planning and to serve as an opportunity to systematically integrate and organize the basic concepts and management methods for each type of landscape (natural green areas, waterfront areas, historic & cultural landscapes, etc.), which had been accumulated during the non-statutory landscape planning process.

Local Government's First Statutory Landscape Plan based on the Scenic Conservation Act

○ The Seoul Basic Landscape Plan was mapped out according to the guidelines on landscape planning notified by the former Ministry of Construction and Transportation (currently the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport) in 2008. Accordingly, the framework for landscape plans was prepared for the first time based on the institutional groundwork. The basic landscape plan clearly presented the areas that required landscape management, and also suggested guidelines on landscape design for buildings to be built within landscape management areas.

<Figure 2> Landscape Basic Management Area and Landscape Intensive Management Area

- Both citizens and public parties could share the necessity for landscape management in the areas concerned by preparing criteria for setting the scope of landscape management and raising civil awareness about the necessity for landscape management. Also, the boundaries of the landscape management areas were drawn with GIS data, so that they could be easily used for mapping out plans and promoting the related projects.

- The landscape design guidelines contain the minimum principles required to protect and preserve valuable landscape resources within the management areas, and are designed to share the value of surrounding landscape resources, facilitate the construction of buildings in consideration of the surrounding landscapes, and create a coherent view of buildings within the same management area.

• Designers should check whether or not buildings belong to a given landscape management area, figure out the type of landscape design guidelines, and envisage the concepts of buildings by considering those guidelines. Prior to approval and review of the buildings, designers should come up with the answers to questions regarding their consideration of the landscape design guidelines for eight items (layout, scale/height, shape/appearance, material, outdoor space, nighttime view, color, and outdoor advertisement) and submit them with the required accompanying documents upon approval and review.

<Table 3> Scale/Height Checklist for Landscape Basic Design Guidelines on Inner/Outer Mountain

| Key Word | Landscape Checklist | Evaluation | |||||

| Harmony with Surroundings | To promote scale and height that harmonizes with inner/outer mountains and surrounding features |

|

|||||

| Skyline | To form a skyline that considers natural geographical features To map out a height plan to secure the view up to the 5th ridge of the summit of mountains |

|

|||||

| No Feeling of Oppression | To avoid excessively large and protruding buildings - Not to block a scenic view or cause a feeling of oppression by folding screen-type buildings or a group of buildings - Divide buildings and design in a slender type in harmony with surrounding landscapes |

|

|||||

| Memo | |||||||

| ※ This box is for designers to write their opinions. You can self-check each item as or use for your explanation about plans. (Related drawing, simple sketch, sentence, etc.) |

|||||||

| Evaluation: Fully considered → ◎ Considered → ○ Not considered → × | |||||||

| Source: Seoul Map Homepage (http://gis.seoul.go.kr) | |||||||

Writing Checklist for Landscape Design Guidelines, Institutionalizing Its Submission and Executing the Landscape Self-Checking System

- Furthermore, it appears that public officials recognized only 50% of the targets subject to checklists submission, and there was a very large deviation in the operational results for each autonomous district (Gu). This suggests that the operational results might vary considerably depending on the attentions and efforts of the public officials concerned.

Agreement on Landscapes and Promotion of Landscape Projects

- For certain preferential landscape projects, the basic landscape plan presented a Seoul Fortress Wall gateway formation project, a station area landscape improvement project, a ground steel structure upgrade, a specialized street formation project, and a gateway landscape formation project. Of these, the gateway landscape formation project was conducted as a pilot project. The landscape agreement project was carried out in three places – namely Ui-dong in Gangbuk-gu, Sinwol 2-dong in Yangcheon-gu, and Junggok-dong in Gwangjin-gu - after accepting applications from the relevant autonomous districts (Gu). However, in the case of Junggok-dong, the agreement was cancelled in accordance with the opinions by residents.

<Figure 3> Gateway Landscape Formation Project (before/after project)

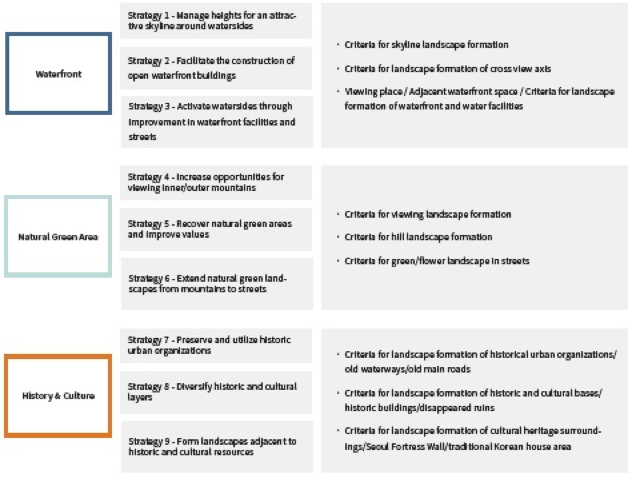

Specific Landscape Planning by Landscape Type

○ The basic landscape plan is a landscape master plan that builds a large framework and outlines the processes for preserving, managing and forming Seoul City landscapes, while the specific landscape plan presents the methods of implementing the preservation, management and formation of landscapes with specific landscape types (forest, waterfront, agricultural/fishing village, history/culture, street, etc.) on the basis of specific environmental elements (nighttime landscape, color, outdoor advertisement, public facilities, etc.), and is based on the landscape plan guidelines.

○ The SMG established a specific landscape plan for four types of landscapes (natural green, waterfront, history/culture and street areas) along with the basic landscape plans. Of these, the street landscape plan was established first in 2009, targeting streets that urgently needed landscape management and that were highly likely to show the effects of improvement. After that, it mapped out a nighttime landscape plan as a specific landscape plan for each specific element in 2009 and established a landscape plan for natural green areas, waterfronts, and history/culture zones in 2010.

<Figure 4> Seoul Landscape Plan System

- The criteria for landscape formation are either planning principles or criteria for establishing a planning direction, so that the related plans (district unit plan, renewal promotion plan, basic plan for urban and residential environment renewal, etc.) and the related projects (landscape project, street environment improvement project, urban planning facilities project, etc.) can be promoted according to a coherent landscape strategy.

<Figure 5> Strategy for Seoul Natural Green, Waterfront and Historic/Cultural Landscape Plans and Criteria for Landscape Formation

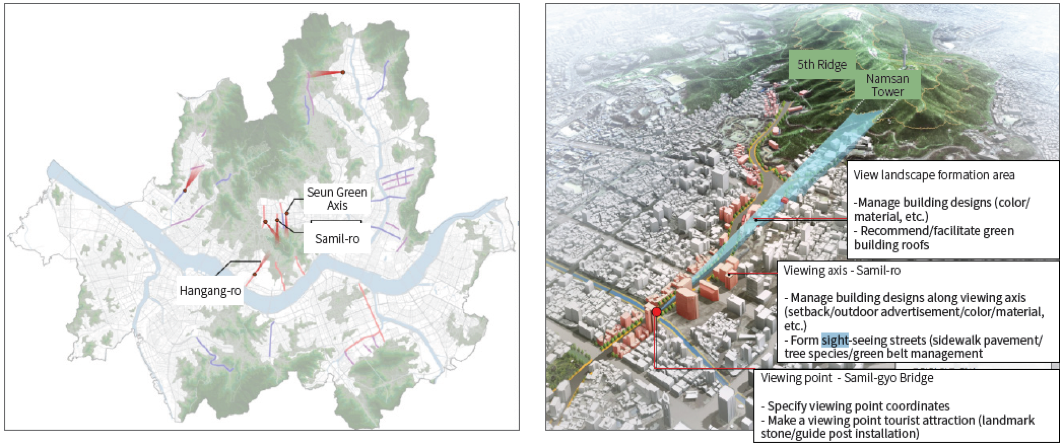

- The government determined 251 viewing points and 35 viewing axes according to the plan, and designated Samil-ro, Hangang-ro, Seun Green Axis, etc. as a view landscape formation area, which overlapped with the No. 1 view point and axis according to the priority of view landscape formation and management.

<Figure 6> Samil-ro View Landscape Formation Area (Seoul Natural Green Landscape Plan, 2010, p71)

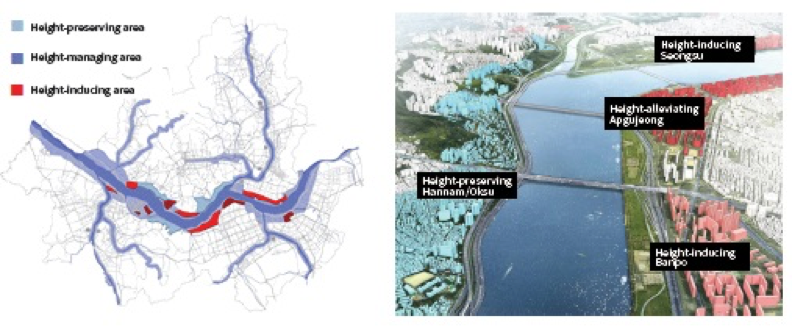

- In particular, the various plans—such as the Hangang Renaissance Master Plan (2007), Hangang Public Reform Plan (2009) and Hangang Stream Local Development Plan Study (2009)—created new waterfront landscapes and presented various issues about the skyline. The waterfront landscape plan suggested a framework for height management of the related plans and designated the sides of the streams without a prior height plan (Jungnangcheon Stream, Bulgwangcheon Stream of Hongje, Dorimcheon Stream of Anyang, Tancheon Stream of Yangjae, etc.) as height management areas.

<Table 4> Classification of Height Management of Waterfront Landscape Plans

| Area | Management Direction | Target Areas |

| Height preservation area | Form a landscape that adapts itself to and harmonizes with natural topography | Mapo/Seogang, Hannam/Oksu, Heukseok/Noryangjin |

| Height management area | Form a landscape in harmony with surrounding areas | Landscape management areas excluding height-preserving/inducing/alleviating areas |

| Height induction area | Form a waterfront landscape full of vitality through the introduction of multi-purpose designs | Hapjeong, Dangsan, Ichon, Banpo, Seongsu and Guui/Jayang |

| Height alleviation area | Create a new landmark landscape around the waterfront area | Yongsan, Yeouido, Apgujeong and Jamsil |

<Figure 7> Height Management-Applied Areas (Seoul Waterfront Landscape Plan, 2010, p55)

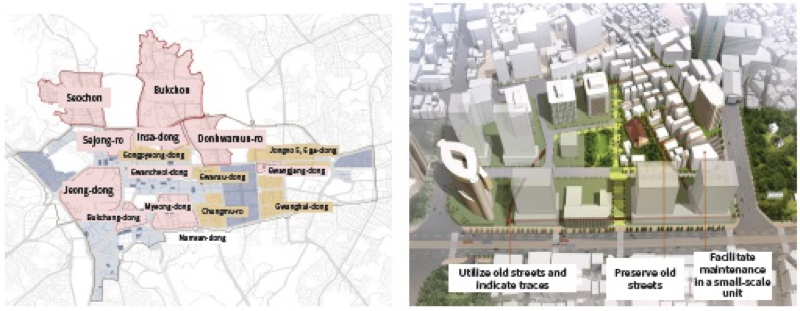

<Table 5> Classification of Historic Urban Organization Areas

| Area | Management Direction | Target Areas |

| Historic Features-preserving district | Maintaining and preserving the original form of old urban organizations | Bukchon, Seochon, Insa-dong and Donhwamun-ro |

| Historic features-managing district | Maintaining and managing the characteristics of old urban organizations | Sejong-ro, Jeong-dong, Bukchang-dong, Myeong-dong, Gwancheol-dong and Gwangjang-dong |

| Small-unit maintenance district | Protecting the characteristics of old urban organizations | Gongpyeong-dong, Gwansu-dong, Chungmu-ro, Jongno 5, 6 ga-dong, Gwanghui-dong, etc. |

| Large-unit maintenance district | Considering and utilizing old urban organizations | Large-scale development plan areas (urban environment maintenance area, renewal promotion area, special planning area, etc.) |

<Figure 8> Historical Urban Organization Areas and Examples (Seoul Historic and Cultural Landscape Plan, 2010, p62)

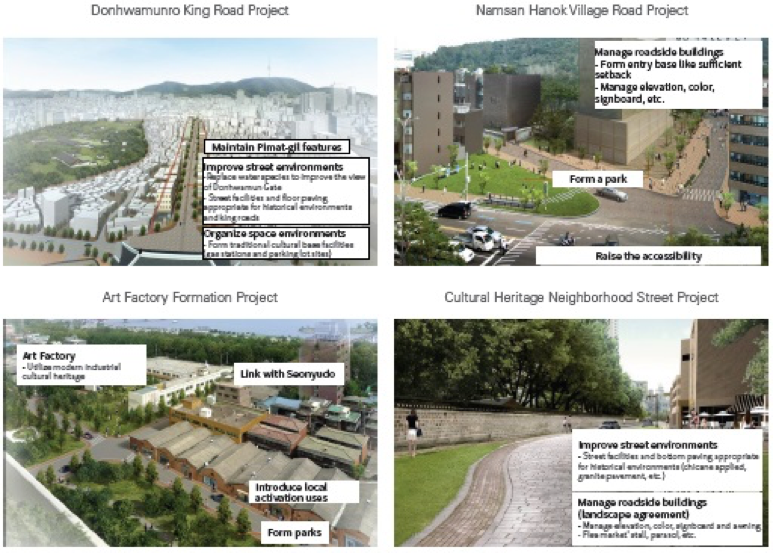

Landscape Project Proposals by Type

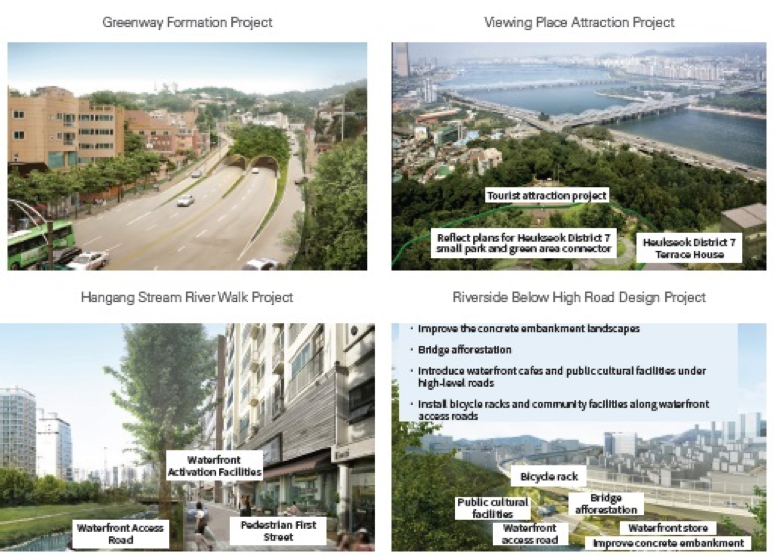

○ The specific landscape plan presents the types of strategic landscape projects that the public sector must promote according to the strategy for each type of landscape. Each landscape project must be promoted in connection with landscape agreements so as to enable local residents to participate in the landscape management.

<Figure 9> Seoul Natural Green/Waterfront/Historic & Cultural Landscape Plan and Examples of Landscape Projects

The 3rd Period | Landscape Plan Renewal according to Changed Conditions

Based on the Scenic Conservation Act, the SMG constructed a framework for landscape plans and prepared its management methods for each type of landscape. However, the existing Scenic Conservation Act did not have the full power of execution for landscape plans due to its lack of management means and the fact that its overly wide scope of target business caused redundancy and confusion. Accordingly, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport revised the Scenic Conservation Act in its entirety in 2014 and the SMG launched the renewal of landscape plans according to the changed situation. It established plans for managing the Han River skyline and the historic center around the four main gates at the same time. Thus, it is necessary to review and reflect upon the related contents in the renewal of landscape plans.

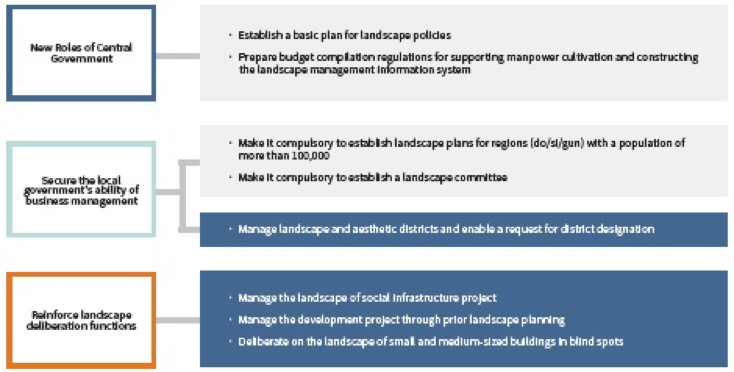

Laying the National Groundwork for Systematic and Integrated Landscape Management

○ Due to the revision of the Scenic Conservation Act, the roles of the central government with regard to landscape policies were newly established. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport is now responsible for establishing and implementing the basic plans for landscape policies every five years, making it compulsory to establish and execute landscape plans for do/si/gun whose population exceeds 100,000, and laying the framework for the local government to secure its power of execution in landscape management.

<Figure 10> Main Contents of Revised Scenic Conservation Act

※ The shaded parts denote the contents of the Seoul landscape policy.

• In the previous Scenic Conservation Act, landscape deliberation was limited exclusively to landscape plans, project approval and landscape agreement permission. In the revised Scenic Conservation Act, the targets of deliberation were extended to social infrastructure, development projects, buildings, etc., thus making it necessary to map out plans for rational landscape deliberation.

• It has become possible to manage and designate landscape and aesthetic districts using landscape plans. It is required to set management directions for maintaining, changing and abolishing such districts by conducting a survey of the actual conditions of the current landscape and aesthetic districts.

Han Riverside Skyline Management

○ In addition, the Han Renaissance Master Plan, which served as a policy attempt to address the Han River as a whole, did not lead to the formation of a long-term plan. In reality, it merely revealed a limit to the comprehensive urban management from the viewpoint of urban landscape, leading to a growing demand for systematic and long-term plans for the Han Riverside. Therefore, the SMG announced directions for the management of the Han Riverside, consisting of four principles and seven detailed management principles for managing the Han River, and planned to materialize the "Han Riverside Management Master Plan" by the first half of 2015 based on this new management direction.

- With regard to the skyline, it has set the guiding principles for the "management of urban spatial structure and hierarchy," "management in harmony with Seoul's unique natural scenic resources," and "management for the protection of historic and cultural heritages," and has prepared height standards according to spatial structures.

<Table 6> Heights by Hangang Riverside Skyline Management Principles

| Use District | Downtown/Subcenter | Region/district-centered | Other Areas |

| Commercial/Semi-Residential | Multipurpose: 51 stories or more, Residential: 35 stories or less | Multipurpose: 50 stories or less, Residential: 35 stories or less | Multi-purpose: 40 stories or less Residential: 35 stories or less |

| Semi-Industrial | Multipurpose: 50 stories or less, Residential: 35 stories or less | ||

| General Residential | General type III: 35 stories or less (residential), Residential: 35 stories or less, Multipurpose: 50 stories or less General type II: 25 stories or less |

General type III: 35 stories or less General type II: 25 stories or less |

|

Management of Historical Center within the Four Main Gates Considering the Changed Downtown Conditions

○ The SMG established the "Basic plan for historic and cultural city management" in 2012 as a basic plan for managing the city within the four main gates as a historic and cultural city, and mapped out the "basic plan for downtown management in consideration of the city’s history and culture" in 2014.

- The basic plan for historic and cultural city management presented the basic principles and directions for managing the city’s historic and cultural resources, and for preserving and utilizing historical spaces and their scope. On the other hand, the basic plan for downtown management presented the policy direction and guidelines for land use, spatial structure, development density, walking and transportation, dwellings, parks & green areas, landscape, and height limit.

Progress

<Table 7> Promotional Details of Landscape Management Policy

| Year | Established laws, systems and plans | Content |

| 1941 | Plan for Joseon streets | Scenic districts designated in order to protect natural landscapes and prevent conurbation. |

| 1994 | Demolition of Namsan Oein Apartments | Apartments demolished according to the Namsan Recovery Master Plan (1991). |

| 1999 | Seoul Architectural Committee Rules on Apartment House Construction Review |

Apartment house landscapes managed based on indexical deliberation criteria and derivative deliberation criteria. |

| 2000 | Enactment of the Urban Planning Act | Landscape districts newly established. |

| Revision of the ordinance on Seoul urban plans | Landscape districts subdivided into natural, visual, waterfront, cultural heritage surroundings, street, and scenic view landscape districts. | |

| 2003 | Enactment of the Land Planning and Utilization Act | Landscape districts designated and subdivided; construction restricted in landscape districts. |

| Revision of the ordinance on urban planning in Seoul | Landscape districts sub-divided into visual, cultural heritage surroundings, and view districts. | |

| 2005 | 2020 Seoul Urban Basic Plan | Landscape plan |

| 2006 | Introduction of average number of stories | Type II General residential area (7 stories or lower) up to average of 11 stories Type II General residential area (12 stories or lower) up to average of 16 stories |

| Revision of Seoul's urban design ordinance | Enacted and executed (July 2006). | |

| Establishment of basic plans for Seoul urban design | Basic Seoul designs conceived. | |

| 2007 | Enactment of the Scenic Conservation Act | Enacted (May 2007) → Executed (November 2007). |

| Enactment of the Framework Act on Building | Enacted (December 2007) → Executed (June 2008). | |

| 2008 | Enactment of the Seoul ordinance on landscapes | Enacted and executed (August 2008). |

| Establishment and systematization of Seoul’s colors | Guidelines on Seoul colors and districts presented. | |

| 2009 | Establishment of Seoul basic landscape plan | Seoul basic landscape plan, street landscape plan and nighttime landscape plan established simultaneously. Pilot operation of the landscape self-check system (April 2009 – March 2011). |

| Improvement plan for average number of stories | Differential criteria (hills, etc.) applied to alleviate the number of stories, with local characteristics reflected. | |

| 2010 | Establishment of specific landscape plans in Seoul | Seoul natural green landscape plan, waterfront landscape plan and historic and cultural landscape plan established. |

| 2011 | Monitoring of the landscape self-check system | Study on landscape management evaluation and improvement plans according to Seoul landscape plan, Seoul Institute (March - August 2011). |

| Establishment of the Seoul basic construction plans | Top plan in the architectural policy based on the Framework Act on Building. | |

| Reform of the Seoul urban design basic plan | Specialized design intensive districts introduced. | |

| 2012 | Implementation of the compulsory landscape self-check system | Landscape self-check system newly named and subject to compulsory execution from January 1, 2012. |

| 2013 | Improvement plan for average number of stories | 7 stories or less for constructing apartments in Type II general residential areas Able to alleviate the number of stories to 13 according to land donation |

| Han Riverside management direction | Skyline management principle (April 2013) | |

| 2014 | 2030 Seoul urban basic plan | Landscape plan |

| Revision of the entire Scenic Conservation Act | Revised as a whole (August 2013) → Executed (February 2014). | |

| Enactment of the Seoul landscape ordinance | • Enacted as a whole and executed (May 2014). | |

| Seoul landscape plan under renewal | • Academic research on Seoul landscape plan renewal, Seoul Institute (May 2014 - February 2015). |

Results

Contribution to Establishing Seoul Identity

Presenting a direction for landscape plans

Improving urban landscapes and raising public awareness with the promotion of landscape agreement and project

References

- Mok Jeong-hun, 2005, “Study on How to Manage Apartment House Heights in Residential Areas: Centering on Type II General Residential Areas”, Seoul Institute

- Park Hyeon-chan, 2014, “Strategy for Landscape Policy Improvement according to Revised Scenic Conservation Act”, Seoul Institute's Policy Report 175

- Park Hyeon-chan, Min Seung-hyeon, 2014, “Study on Landscape Policy Improvement Directions in Seoul according to Revised Scenic Conservation Act," Seoul Institute

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 1991, Namsan Recovery Master Plan

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2000, Seoul Plan for Mountain Scenic Landscape Conservation

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2002, Seoul Plan for Mountain Viewing Landscape Conservation

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2005, Seoul Basic Plan for Landscape Management

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2009, Seoul Basic Landscape Plan

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2010, Seoul Plan for Street Landscapes

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2010, Seoul Plan for Natural Green Landscapes

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2010, Seoul Waterfront Landscape Plan

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2010, Seoul Plan for Historic and Cultural Landscapes

- Seoul Metropolitan City, 2012, Basic Plan for Historic and Cultural City Management in Four Gates of Seoul

- Lee Seong-chang, Park Hyeon-chan, 2011, “Study on Landscape Management Evaluation and Improvement Plans according to Seoul Landscape Plan,” Seoul Institute

.png)