Residential Environment Improvement Program for the City of Seoul

Background to the Residential Environment Improvement Program

Thanks to the intensive economic growth of the 1970s and 1980s, housing demand snowballed in Seoul. Naturally, the government followed aggressive policies to provide sufficient housing for its people. Urbanization slowed somewhat in the 1990s, leading to a growing demand for government policy to address the need for improvements to areas where housing had deteriorated, including redevelopment. The initiative which began in the 1960s to improve living environment can be divided into three programs: housing redevelopment, housing reconstruction, and residential environment improvement. Each was based on different laws and implemented through different procedures and methods. Of these three, the last played a crucial role in supplying new housing and improving significantly deteriorating areas, particularly in Seoul where the available land for development is limited.

The real estate market had been very active due to housing demand until the Asian financial crisis in 1997. The market then stagnated and the government was asked to revitalize it. The existing improvement programs up to that time had been carried out for profit on a small scale, independent of each other, without consideration of urban infrastructure that needed a broader approach. Various problems arose as a result, such as an overburdened infrastructure, damage to the cityscape, and loss of needed residential areas. To resolve these problems, improvements had to be made at a broader level and in a systematic manner.

Extensive issues were created by the execution of individual programs under different laws. These programs included: the Housing Redevelopment Program pursuant to the Urban Redevelopment Act; the Housing Reconstruction Program pursuant to the Housing Construction Promotion Act; and the Residential Environment Improvement Program pursuant to the Act on Temporary Measures for Improvement of Dwellings & Other Living Conditions for Low-Income Urban Residents. To address the issues created, the three separate laws were integrated into the Act on Maintenance & Improvement of Urban Areas and Dwelling Conditions for Residents (the “Improvement Act”) in 2003. In the Improvement Act, and the establishment of a Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas was made mandatory in an effort to minimize the undesirable outcomes of poorly coordinating the separate improvement programs.

<Figure 1> Enactment of the Improvement Act

Summary

Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2010

The Improvement Act required that a Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas be established, which was to be a higher-level plan for the individual improvement plans, for better integrated urban management. The Redevelopment Master Plan would then be carried out in connection with its own higher plan – the Basic Urban Plan – as well as with other urban management plans, making it easier to respond to changes with more flexibility. According to the Act, the basic principles and development guidelines would have to be presented, including such information as target areas, directions, facility standards, development density standards, and methodology. In the following paragraphs, the major specifics in the Redevelopment Master Plan are introduced.

The first initiative introduced to the Redevelopment Master Plan was the “community sphere”, a concept used to develop wider-area plans. “Community sphere” refers to the small living environment for a community. This is the basic unit at which plans for residential management, infrastructure improvement, and house leasing are developed. The community sphere served as a basis for planning infrastructure. Whereas the individual improvement programs that had been implemented for profit led to the previously mentioned extensive urban problems (an overburdened infrastructure, damage to the cityscape, and loss of needed residential areas), the community sphere plan took a broader and more systematic view of infrastructure improvement so as to maximize the effects of improvement, make reasonable adjustments to physical features (e.g., roads, geography-related matters), and allow for reasonable access to pedestrians and other rights.

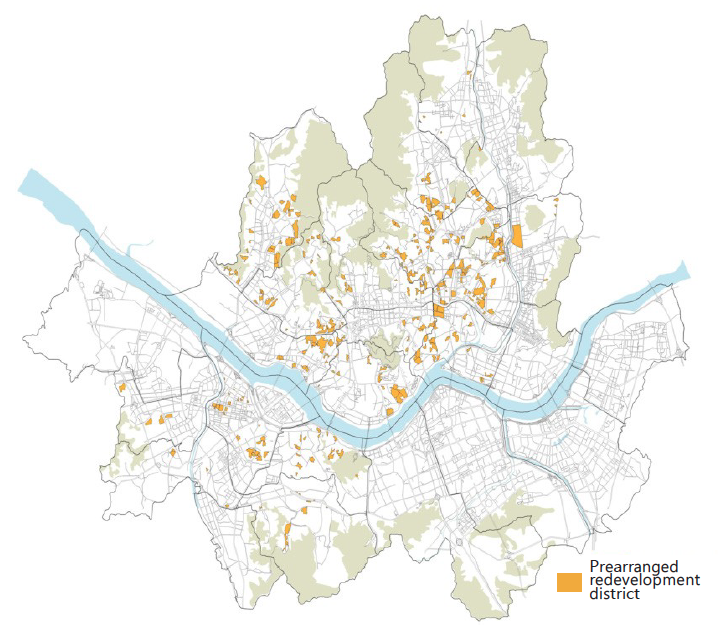

Second, the concept of “prearranged improvement for target districts” was introduced to allow for the “Plan First, Develop Later” scheme. The districts that were to be improved would be designated, and then selected for redevelopment, reconstruction, or residential improvement. This system of designating a target area granted greater flexibility and encouraged a broader perspective of the improvement from the point of view of the entire urban planning scheme. However, this system, adopted to “plan first and develop later”, was altered to “designate first, plan next, and improve later”, quite the opposite of what was originally intended. In fact, the system led investors to expect high returns from development and caused property prices to rise. This in turn pushed program costs up, not to mention the fact that executing programs individually at the prearranged district level undermined systematic planning of roads and other infrastructure facilities.

<Figure 2> Prearranged Improvement for Target Districts for the Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2010 in Seoul

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2004, Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2010 for Seoul, Seoul Metropolitan Government Redevelopment Program

Third, height and density management was introduced for the cityscape. Under the Basic Housing Redevelopment Plan, high-rise buildings were allowed on hills or in low-rise residential areas as there were no regulations on number of floors when calculating estimated floor space. However, the Redevelopment Master Plan used the floor specifications from the type classifications under the General Residential Area, promoting adequate development by land use and systematic improvement of the cityscape.

Residential Environment Improvement Program

The Improvement Act is utilized to assist implementation of the Residential Environment Improvement Program. The program can be introduced pursuant to this Act, provided that all the physical conditions and legal grounds (consent from owners, etc.) for the area designation are met. The Improvement Act categorizes parts of the Residential Environment Improvement Program by target area characteristics into: the Residential Environment Improvement Program, the Housing Redevelopment Program, and the Housing Reconstruction Program. It is also by these characteristics of the target area that the type of program is determined. The Residential Environment Improvement Program is implemented at the lot unit level, targeting areas with high concentrations of significantly deteriorating buildings and low-income earners, and where the infrastructure is extremely poor. The Housing Redevelopment Program is for areas with high concentrations of significantly deteriorating buildings and where the infrastructure is poor. The Housing Reconstruction Program is for areas where the infrastructure is good but contain a high concentration of significantly deteriorating buildings. These programs are further divided according to the entity that carries out the programs: private development, public development, and joint development. The methods utilized include management and disposal, improvement, housing construction, replotting, and acceptance.

The procedures for housing redevelopment and reconstruction programs include planning, preparation, execution, and completion. In the planning stage, an improvement plan is developed and target areas designated. The preparation stage requires that consent from a majority of land owners, etc. be obtained to organize a program committee or a resident council and obtain approval for the organization of an association. In the execution stage, approval is obtained and the construction company selected. After approval is granted for the management and disposal plan, significantly deteriorating buildings are demolished to make way for new construction. The program is concluded once construction is completed, residents move in, liquidation is settled, and the association disbands.

Advancement of Residential Environment Improvement Policies

Once the Residential Environment Improvement Program and the New Town Program (a broader level program) were pursued in earnest, problems again began to surface. Only a small number of original residents returned; small, affordable houses disappeared; housing and jeonse lease prices jumped; and conflict frequently occurred between residents. The City of Seoul therefore organized the Advisory Committee for Residential Environment Improvement Policy to come up with fundamental solutions to these problems.

The Advisory Committee worked to address the current issues – a lack of sufficient housing for low-income families; development of the target area management system; diversification of housing types; expansion of the public role in the improvement programs; and revision of the residential area change management system. Accordingly, the City of Seoul maintained the basic structure of existing residential areas, comprised of low-rise buildings, in 2009, while introducing a public management system by which the role of the public sector was strengthened in the “Human Town” programs and improvement programs. The city government also developed a tool to calculate improvement program costs, endeavoring to offer an enhanced system for the tenants.

Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2020

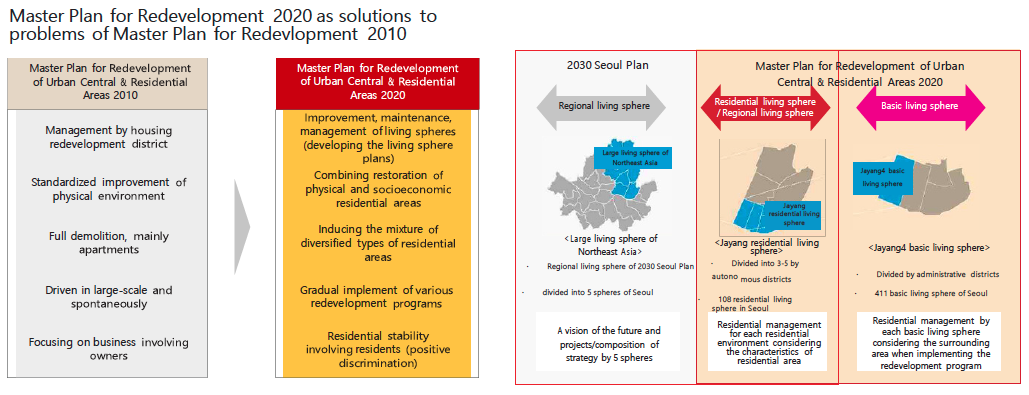

Of the individual improvement plans, the Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2020 is said to be the key comprehensive people- and location-oriented residential area management plan. It offers systematic improvement of infrastructure and effective use of local resources, and enables overarching improvement, maintenance and management of living spheres. Revised in February 2012, the Improvement Act requires that plans are developed at the living sphere level as part of the Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas. The Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2020 replaced the living sphere plan with a plan on target areas and plans by stage, which ensured consistency of the living sphere plan with the Basic Seoul Urban Plan for 2030. For its residential restoration policy, Seoul suggested 3 goals: Residential areas which enhance the value of life and the future; Residential areas that appreciate people and the community; and Residential areas shaped by residents throughout the entire process.

<Figure 3> Direction of the Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2020

Source: Internal data, Housing Policy Bureau, Seoul Metropolitan Government (2013)

| Basic Improvement Plan 2010 | Basic Improvement Plan 2020 |

|---|---|

| Unit management of target areas | Improvement, maintenance and management at the “living sphere” level (corresponding plans to be established) |

| Improvement of monotonous physical environments | Integration of residential areas in physical & socioeconomic terms |

| Full demolition, mostly apartments | Amalgamation of various residential types |

| Simultaneous, full-scale | Gradual introduction of various improvement programs |

| For-profit, owner-oriented | Resident-focused, resident stability(more focus on disadvantaged groups) |

The following paragraphs are a summary of the Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2020 as built on the above goals:

First, residential areas fall under comprehensive management under the living sphere plan, which replaces the target area system. The living sphere plan is comprised of the residential sphere plan – a statutory plan built by the City of Seoul – and the basic sphere plan – an administrative plan developed by autonomous districts. The roles and details are categorized by this structure.

Second, the Residential Environment Index is introduced to objectively analyze the living sphere, a management system to create residential environment at the global level that meets international standards. It is comprised of 35 indices – 25 physical and 10 socioeconomic. Analysis of the indices influences the direction of planning.

Third, a new management system is introduced in place of the target area system. The new standard, called the Residential Improvement Index is introduced to designate areas. The new system also manages the supply and loss of housing and provides guidelines for the improvement programs.

Fourth, the residential environment management program types are diversified. A Residential Management Index is also introduced to determine whether public assistance is needed, and restoration programs are actively pursued to maintain and manage the residential areas.

Fifth, management of special residential areas is strengthened (residential areas with low-rise buildings, adjacent to the city walls, near the major mountains, waterways, or areas such as Bukchon).

The living sphere plans ensure that the existing basic improvement plans focus on improvement, maintenance and management of residential areas. With an aim to manage residential areas through living spheres and meet local needs, housing supply plans were developed to help install infrastructure, promote resident stability, and ensure a pleasant living environment in each sphere.

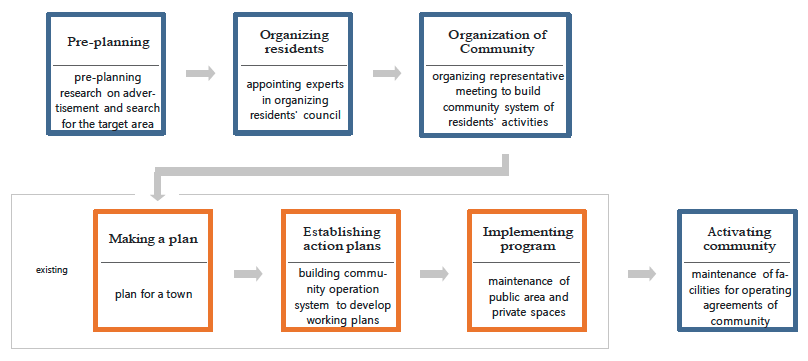

Emergence of Resident-Involved Restoration Programs

The negative impacts from the existing improvement plans that leaned heavily on demolition led the public to call for an alternative. In the widespread low-growth trend, the improvement plans experienced paradigm changes, with shifts from owners to residents and from demolition to preservation. It was in this process that residents were encouraged to be involved in the restoration programs. Resident-Involved Restoration Programs refer to “tailored plans and programs, including the improvement of living environment, construction of infrastructure, and assistance with home improvements in order to resolve complaints and address issues that arise in small communities with a concentration of detached/multi-household housing and townhouses.” (Seoul Metropolitan Government 2013b, p.27)

Revised in February 2012, the Improvement Act included new programs – the Residential Environment Improvement Program and the Block-Unit Housing Rearrangement Program – in addition to the Housing Redevelopment Program, the Housing Reconstruction Program, and the residential environment improvement program. The new programs are pursued as part of the Resident-Involved Restoration Programs in connection with the Make My Community program.

Residential Environment Improvement Program

In an effort to preserve and improve low-rise residential buildings without resorting to demolition, the Improvement Act, revised in February 2012, introduced a new method to improve the residential environment. In 2010, the concept of the “Human Town” was adopted, which is dedicated to preserving the residential areas of low-income families, providing needed housing, and improving the environment occupied by low-rise residential buildings. This Human Town program captured the core problem in such areas with low-rise residential buildings – safety and security – and added convenient infrastructure and amenities. In the beginning, there were no legal grounds or institutional basis in the Improvement Act to support the Human Town program. Financing was also temporary, funded by a portion of the Urban & Residential Environment Improvement Fund, which, as it became apparent, was not a permanent solution. The Human Town needed an institutional framework for financing.

The new Residential Environment Improvement Program also included the existing Human Town programs, which still continued afterwards. Under the program structure, the public sector assists with building the infrastructure or public facilities for the community. The residents take the lead in creating a community and take an active part in the restoration of the community environment. The targets include residential areas with a concentration of detached and multi-unit housing, General Residential Area Types 1 and 2 and the areas to be removed from the improvement target list, and the areas for reconstruction or redevelopment of detached housing where 50% or more of the (land) owners agree with the shift to the Residential Environment Improvement Program. To help the residents take the lead, a community is created first. Then overall plans are made, action plans drafted, and the program launched. This process is designed to maintain community activities after the program is successfully completed.

<Figure 4> Process of the Residential Environment Improvement Program

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2012, Development of an Alternative Model and Pilot Program for the New Town Redevelopment & Improvement Program

The public sector provides assistance for basic infrastructure (roads, parking lots, squares, security lights, CCTV etc.) and specific streets and walking trails for pedestrians, with resident-proposed ideas given priority. Support includes assistance with public facilities for residents (community centers, childcare centers, senior centers, public housing for temporary lease, etc.), waste treatment facilities, no-wall campaign, and the “Green Parking” program. Experts in master planning and community are dispatched to design future plans for the area and put the plan into action. Each program district has on/offline channels that provide consultation in accordance with income level and building type, offering opinions on such things as home improvements, their scope and cost estimates. These channels also guide residents to institutions that offer loans, and if necessary, those at a low interest rate. Financing is available for individual or joint renovation or improvement of housing or other buildings; 80% of the cost of improvement or construction within the residential environment management district may be taken out as a loan. Home renovation and improvement standards are available in manual form to help residents understand the requirements and procedures.

In addition to the 8 areas where the existing Human Town programs were absorbed into the Residential Environment Improvement Program, the City of Seoul plans to add 15 new areas each year to continue the program. The areas designated for the Residential Environment Improvement Program as of July 1, 2014 can be seen in Table 1 below.

<Table 1> Areas Designated for the Residential Environment Improvement Program in Seoul

|

|

Areas to be |

Areas to |

General Areas |

Special Areas |

Number of |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Selected before 2011 |

Yeonnam-dong, Bukgajwa-dong |

Heukseok-dong, Siheung-dong, Gireum-dong |

Banghak-dong, Onsu-dong |

|

7 |

|

Selected in 2012 |

Samseon-dong, Guro-dong |

Siheung-dong |

Gaebong-dong, Eungam-dong, Shinsa-dong, Hwigyeong-dong, Sangdo-dong, Miah-dong, Jamsil-dong |

Dobong-dong, Daerim-dong, Jeungneung-dong, Hongje-dong |

14 |

|

Selected in 2013 |

Hongeun-dong (2), Shinwol-dong, Gongneung-dong, Miah-dong, Jeungneung-dong, Yeokchon-dong, Seokgwan-dong, Suyu-dong, Amsa-dong, Seongnae-dong, Geumho-dong (2), Bulgwang-dong, Sangdo-dong, Guro-dong, Hwigyeong-dong, Siheung-dong, |

|

Sangwolgok-dong, Shinwol-dong, Dorim-dong, Daerim-dong |

Jeonnong-dong |

23 |

|

Selected in 2014 |

Samseon-dong, Garibong-dong |

|

Yeokchon-dong, Doksan-dong |

|

4 |

|

Source: Summary from the Magok Program on Seoul Housing, Urban Planning & Real Estate website (http://citybuild.seoul.go.kr/archives/2997). |

|||||

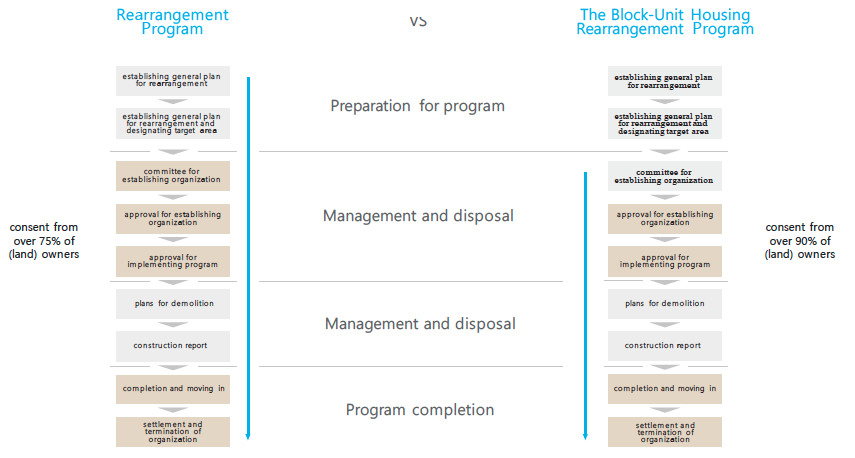

Block-Unit Housing Rearrangement Program

The Block-Unit Housing Rearrangement Program was introduced alongside the Residential Environment Improvement Program, after revision of the Improvement Act in February 2012. While the existing improvement program relied on the full demolition of significantly deteriorating houses across wide areas, the newer system was designed to maintain the urban structure and street networks and build small multi-unit dwellings.

Target areas include blocks surrounded by city/gun-district roads, 10,000 m2 or less in area, and without any through road except for those 4m or less in width. This program could be launched with the following conditions: in some or all of the block-units that met such requirements, two-thirds or more of all buildings must be significantly deteriorating, and there must be 20 or more households in existing detached houses and multi-unit buildings.

The entity that pursues the program may do so i) as an association comprised of land and house owners, or ii) jointly with the city mayor/gun-district governor, Housing Corporation, construction company, registered entity, or legitimately approved entity when the association obtains consent from the majority of its members. To organize an association, 8 out of 10 (land) owners covering two-thirds of the relevant land area must consent.

The Block-Unit Housing Rearrangement Program omits some of the processes found in existing improvement programs (designation of improvement target areas, establishment of improvement plans etc.) stipulated in the Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas and starts from the stage of obtaining approval for the organization of an association.

<Figure 5> Block-unit Housing Rearrangement Program Process

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2012, Development of an Alternative Model and Pilot Program for the New Town Redevelopment & Improvement Program

Changes to the System

Major Revisions to the Improvement Act

Since its enactment, the Improvement Act has undergone multiple revisions. The following paragraphs summarize the two major revisions.

The first revision in 2009 provided plans for adequate compensation for residential and commercial tenants. As part of a more attractive compensation package and to encourage tenants to return, commercial tenants were given priority for purchase/tenancy, and compensation for closing the business was increased from 3 months of estimated business revenue to 4 months. A tenant migration plan was incorporated in program execution, and an ear given to tenants, with public housing for lease also made available for temporary use by these tenants. Moreover, the letter approving construction indicated the demolition schedule allowing residents to plan ahead. A dispute committee was formed to address conflicts between the association and tenants, and the obligation to properly compensate tenants became stronger. Any loss suffered by the association due to the additional tenant compensation was offset by the benefits from easing the floor space ratio.

In 2012, the second revision laid the groundwork for a program exit strategy and alternatives. A “sunset system” was introduced to remove improvement target areas from the list if and when certain conditions (e.g., resident consent) were met even if it proved difficult to pursue the program due to the sluggish property market or conflict with residents. The competent administrative government was also allowed to approve the program committee or cancel association approval in accordance with input from residents. This revision also allowed for assistance from the local government entity to help replace some of the money spent by the cancelled program committee, and information could be provided to the (land) owners relevant and necessary for the residents to make informed decisions, such as the approximate costs of the program or estimated contributions. In the meantime, an institutional basis was developed to encourage sustainable restoration of the residential areas. Where areas were removed from the improvement target area list, the Block-Unit Housing Rearrangement Program and the Residential Environment Improvement Program were able to be introduced – an alternative to the old method of demolition instead of improvement, maintenance and management of the areas.

Various measures were taken to make the program launching in designated areas successful. In areas under the public management system, relevant regulations were loosened, the process was simplified (organization of a program committee was unnecessary, etc.), and the floor space ratio applied in the redevelopment programs could be increased to the legal maximum. The increased floor space ratio could be offset by the construction of small houses. Furthermore, the legal framework was laid to allow city mayors or gun-district governors to request verification of the feasibility of the management and disposal plan. The scope of the public sector’s role was also expanded by adding responsibilities from developing the residential or migration plan for tenants to assisting with the development of the management and disposal plan.

The revisions provided a basis for the residential area management plan according to living sphere. There was no need to designate the areas to be improved, and integration of improvement, maintenance and management of each living sphere was made possible. It became mandatory to provide information to the residents and listen to their input to ensure the free exercise of their rights to know and keep the program transparent throughout the process. Future disputes were to be prevented by providing information such as the estimated compensation to the (land) owners before agreeing to organization of an association. Many institutional measures were implemented to improve the flow of information to the residents. The system for obtaining consent from the residents became more effective. The percentage of direct participation in the major general meetings grew from 10% to 20%, and even general meeting resolutions on development of the program execution plan would need to be agreed by a majority of the association members. Penalties were strengthened for corruption or irregularities in the process of selecting a construction company or electing an association executive.

Enactment and Revision of the Ordinance on Seoul Urban & Residential Environment Improvement

Based on the Improvement Act initiated in 2003, the Ordinance on Seoul Urban & Residential Environment Improvement (the “Improvement Ordinance”) was passed in December 2003, which dealt with matters stipulated in the law in more detail. The Improvement Ordinance has since been revised a few times. Pursuant to revision of the Improvement Act in February and of the Enforcement Decree of the Improvement Act in August 2012, the Improvement Ordinance was revised twice.

The first revision addressed the following: requests for association disbanding and the scope of consent required from the (land) owners for cancellation of the program committee and association approval in cases where a program was canceled; the percentage of consent required for (land) owners to request the head of the gu-office to disclose information on the total cost of the improvement program or estimated compensation; and the percentage and use of small houses built to offset the increased floor space ratio. To inject vitality into the program area, the revised Ordinance included a public management system and expanded the scope of assistance. The scope of public management covered assistance for development of residential and migration plans for tenants and for the management and disposal plan. In an attempt to boost acceptance of the improvement program in designated areas, input from residents was carefully considered and their opinions sought on designation of areas for improvement, (land) owners were given the opportunity to state their desired housing size and compensation, and tenants encouraged to move back in after improvements and lease a unit. Measures designed to help tenants were also included, such as relaxing eligibility requirements for those living on Basic Livelihood benefits. The methodology and procedures were specified to adjust the program approval timeline and the management and disposal plan. If an excess of 1% of the housing stock in the autonomous district or the number of existing housing in the improvement program area exceeded 2,000 units, that area was subject to deliberation. Requirements for an area to be designated for the Housing Reconstruction Program was that the improvement plan should be for 10,000m2 or more, and the area should be occupied by a concentration of residential buildings, two-thirds of which would be scheduled for reconstruction.

The second revision included details on the scope and method of assistance with program committee expenses described in the law and the enforcement decrees, and organization and operation of a committee to monitor program committee expenses. The revision also allowed the facilities used by residents (management office, security office, gym facilities, library, waste treatment facilities etc.) to be classified as joint facilities as part of the Residential Environment Improvement Program, which would make their construction eligible for assistance from the public sector (such public assistance and loans facilitated the programs). Furthermore, the revised ordinance included information on the procedures to follow once a program committee was disbanded in the area under public management as well as on the regulations relevant to removing eligibility requirements for the detached housing reconstruction program.

Organizational Reshuffling

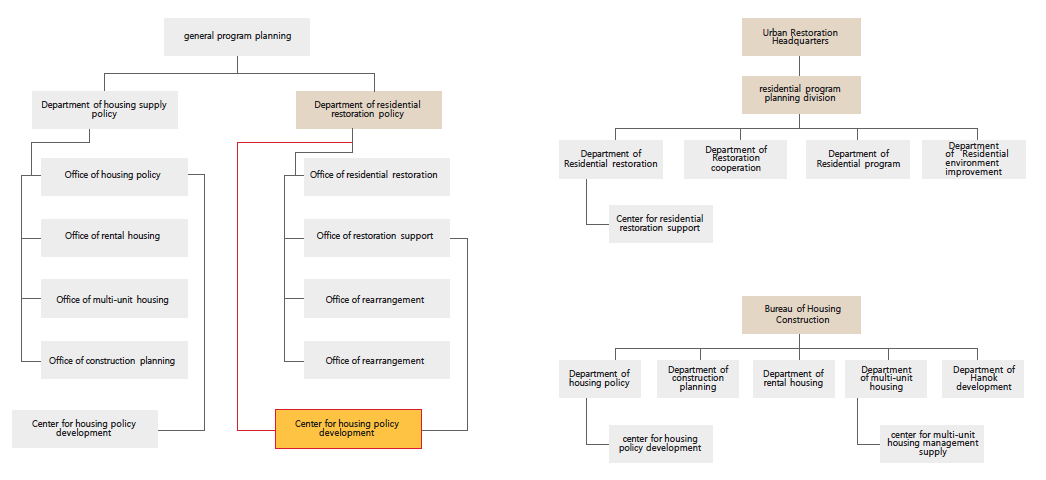

Since enactment of the Improvement Act, the Residential Environment Improvement Program for Seoul has been under the supervision of the Department of Housing Improvement, the Housing Bureau. Leading up to the fifth popular election of Seoul, the New Town program grew sluggish. The Balanced Development Headquarters were dismantled, and the functions of the New Town program were absorbed by the Housing Bureau. In 2010, the Housing Bureau was expanded and renamed the Housing Headquarters. The Department of Housing Improvement was reorganized as the Department of Residential Restoration in July 2011 when discussions on housing restoration became active once more. In December of the same year, the Housing Headquarters was again changed to the Office of Housing Policy with the goal of increasing the supply of low-income housing and enhancing residential welfare. In line with the 1.30 New Town redevelopment plan announced in early 2012, the Residential Restoration Support Center was created in September under the Office of Housing Policy’s Housing Restoration Program in order to handle disputes from the improvement programs and seek alternative resolutions. It works with the Department of Restoration Assistance of the Office of Housing Policy for any necessary administrative assistance.

In January 2015, the Urban Restoration Headquarters was created, and housing restoration-related tasks were transferred from the Office of Housing Policy to the Urban Restoration Headquarters’ Residential Program Planning Division. The Residential Restoration Support Center works with the Department of Residential Restoration at the Headquarters and receives the necessary administrative assistance. In charge of housing-related matters, the Office of Housing Policy was reorganized into the Bureau of Housing Construction with 5 departments (Residential Restoration, Restoration Cooperation, Residential Program, and Residential Environment Improvement).

<Figure 6> Reorganized Seoul City Housing Organizations

Major Achievements

Improvement of Significantly Deteriorating Housing

Improved Infrastructure Such as Roads & Parks

New Housing in Existing Built-up Areas

Housing for Lease

Overall Quality Improvement of Housing Stock & Residential Environment

Limitations & Challenges

Limitations of the Residential Environment Improvement Program

The Residential Environment Improvement Program is characterized by its full demolition approach based on the mechanism of the real estate market. While this approach helped improve residential areas in a short period of time, it also resulted in various problems. When a group of housing units reaches a certain level of deterioration, it is completely demolished and a medium-sized apartment complex put in its place. The loss of affordable housing aggravated lower-income tenants and residents, unable to afford the new housing. This made it more difficult to return to the area and led to the loss of the existing community. Because the infrastructure and landscape of adjacent areas were not considered, these areas were occupied with high-rise, high-density buildings, creating typical issues that accompany any poorly-managed development and adding a monotonous appearance to the cityscape. Moreover, apartment complexes have led to interruptions in the urban space. During the programs, conflicts occurred between residents for and against the program, and between landowners and tenants regarding compensation and migration. The recent slowdown in the real estate market has also stunted the improvement programs, and residents are under pressure from the excessive share. The program now faces a number of limitations.

The Need to Switch to a Residential Restoration Paradigm

To move beyond the limitations of the Residential Environment Improvement Program, it is important to switch to a residential restoration paradigm. Residential restoration in line with socioeconomic changes respects the existing community and encourages residents to take the lead in restoring the area. It cannot be done in a short period of time; it requires active participation by the residents in order to create a sustainable and cyclical approach to residential restoration.

Such resident participation in the restoration is a break from the existing programs led by the public sector that resulted in monotonous types of housing and residential areas. It is necessary to provide for an institutional framework in which residents are encouraged to take leadership in creating diversified types of housing, and the pilot program has laid the foundation for further execution.

Implications

When quantitative growth was important during the period of condensed urbanization, the greatest virtue was to supply what was needed as quickly as possible. Residential environment improvement that began with full demolition was effective in improving areas with significantly deteriorating houses and supplying new units in a short period of time. It contributed significantly to addressing Seoul’s housing shortage and elevating the overall quality. However, it also meant that existing communities were destroyed and the uniqueness that defined those areas was lost. The Residential Environment Improvement Program and its purpose, targets and approach have long been a subject of controversy.

Seoul’s recent restoration programs encouraging resident involvement is an alternative that can address the side-effects of existing programs and pursue improvement in a more gradual manner. However, it requires sustainable financing and new ideas to encourage residents to be voluntarily involved.

In the future, the Resident Involved Restoration Programs will need to identify detailed strategies based on the following 5 action goals:

First, raise public awareness, engage in active promotion through contests, provide education to create consensus, and form a network of experts. Second, launch the Village Worker campaign, discover and support local businesses and social enterprises, and foster local talent and expert personnel. Third, build a public support system that provides administrative and financial assistance at each stage, dispatches experts, and secures the necessary funding. Fourth, overhaul the relevant institutional framework and systems to facilitate the programs (build inter-departmental collaboration, create dedicated teams for the programs at corresponding autonomous government offices, etc.). Fifth, launch and monitor Stage 1 of the pilot program, refining as necessary to ensure the stability of later expansion of the program.

Introduction of the concept of “living spheres” laid the groundwork for a more comprehensive residential area management as it provides for simultaneous improvement, maintenance and management of the residential areas. Because this type of program has more targets than the existing plans do and requires more specific details, it is critical that the public and private sectors as well as residents and other relevant entities work together to ensure the success of the plans.

References

The Seoul Development Institute, 2001, “Spatial Changes in 20th Century Seoul”.

Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2004, “Master Plan for Redevelopment of Urban Central & Residential Areas 2010 for Seoul”, Seoul Metropolitan Government Redevelopment Program.

Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2012, “Follow-up & Challenges for Seoul’s New Town Redevelopment Program”.

Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2013a, “Development of an Alternative Model and Pilot Program for the New Town Redevelopment & Improvement Program”.Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2013b, “Create Together, Enjoy Together: a Manual for Seoul’s Resident Involved Restoration Program”.