[USA_Slate Magazine] Life in Little Pyongyang

Life in Little Pyongyang

Seoul’s Haebangchon neighborhood was founded by isolated North Koreans but is now an epicenter for diversity.

Aug. 22, 2017 By David Josef Volodzko

See the Original(Click here)

Each week, Roads & Kingdoms and Slate publish a new dispatch from around the globe. For more foreign correspondence mixed with food, war, travel, and photography, visit its online magazine or follow @roadskingdoms on Twitter.

“They’re all dead,” says Daniel Park, shrugging and taking a drink. “They’re just dead.”

We’re sitting at a table in Hair of the Dog, the kind of pub that invites long philosophical talks over beer, in Seoul’s most diverse neighborhood, Haebangchon. This was once the city’s own Little Pyongyang, filled with North Korean defectors who fled home at the end of the Korean War in July of 1955, and Park, whose parents were among them, is explaining why almost none are left.

“Mi padre, he died in his ’90s, and most who came didn’t live so long,” he says. “The next generation, they moved to other areas in the city. New defectors go all over.”

Park is a 53-year-old who looks like he’s 40, smiles like he just scammed you out of a 10-spot, and peppers his sentences with Spanish, a relic of his times spent studying psychology in El Salvador. He looks at the bar for a moment, lost, then leans over the table toward me.

“Mi padre was born in Pyongyang. He science at Kim Il Sung University. When he come here, he buy un edificio,” he says, using the Spanish word for building. “So, no need for work, just drink all day, like me.”

Park leans back and smiles. I ask if it’s an apartment building.

“No, shops. Basement and two floors. He to me. Now I make $10,000 a month,” he says, shrugging. “No need for work.”

Given the hardships required to journey to South Korea at that time, it’s astounding that two people could make the trip and have their son wind up a slumlord millionaire in Seoul.

In the summer of 1955, the bombed-out ruins of Pyongyang were still smoldering when groups of North Koreans began slipping south through the borderlands. They crept onto trains and rode through tunnels and mountain passes, clinging to the roofs of passenger cars to avoid inspection agents, leaping off before train station security could spot them, then making their way through burning forests and desolate villages gutted by U.S. air strikes to the banks of the icy Tumen or Anbok rivers, where they crossed at night to evade military patrols or sniper guards.

But freedom brought troubles of another kind. Those who made it, sometimes known as gwihwan dongpo or “returned brothers,” settled in the slums of Seoul, where they faced terrible prejudice—and still do. Even today, almost half of North Korean defectors say they face discrimination in South Korea.

“They called me names, treating me like an idiot, and didn’t pay me as much as others doing the same work, just because I was from the North,” Kwon Chol-nam, who defected in 2014, said in a New York Times piece published this month. “In the North, I may not be rich, but I would better understand people around me and wouldn’t be treated like dirt as I have been in the South.”

Kwon isn’t the only one who wants to return, either. In 2012, a former South Korean MP claimed that already that year more than 100 defectors had gone back, which is about 7 percent the annual number of defectors at the time, and this is despite the fact that upon their return, they could be sent to labor camps where, as one former prisoner told the BBC, people fight over maggots that grow out of corpses and catch rats that they eat raw, “their mouths covered in blood.”

Seoul Tower on Namsan and the neighborhood of Haebangchon below.

“They’re all dead,” says Daniel Park, shrugging and taking a drink. “They’re just dead.”

We’re sitting at a table in Hair of the Dog, the kind of pub that invites long philosophical talks over beer, in Seoul’s most diverse neighborhood, Haebangchon. This was once the city’s own Little Pyongyang, filled with North Korean defectors who fled home at the end of the Korean War in July of 1955, and Park, whose parents were among them, is explaining why almost none are left.

“Mi padre, he died in his ’90s, and most who came didn’t live so long,” he says. “The next generation, they moved to other areas in the city. New defectors go all over.”

Park is a 53-year-old who looks like he’s 40, smiles like he just scammed you out of a 10-spot, and peppers his sentences with Spanish, a relic of his times spent studying psychology in El Salvador. He looks at the bar for a moment, lost, then leans over the table toward me.

“Mi padre was born in Pyongyang. He science at Kim Il Sung University. When he come here, he buy un edificio,” he says, using the Spanish word for building. “So, no need for work, just drink all day, like me.”

Park leans back and smiles. I ask if it’s an apartment building.

“No, shops. Basement and two floors. He to me. Now I make $10,000 a month,” he says, shrugging. “No need for work.”

Given the hardships required to journey to South Korea at that time, it’s astounding that two people could make the trip and have their son wind up a slumlord millionaire in Seoul.

In the summer of 1955, the bombed-out ruins of Pyongyang were still smoldering when groups of North Koreans began slipping south through the borderlands. They crept onto trains and rode through tunnels and mountain passes, clinging to the roofs of passenger cars to avoid inspection agents, leaping off before train station security could spot them, then making their way through burning forests and desolate villages gutted by U.S. air strikes to the banks of the icy Tumen or Anbok rivers, where they crossed at night to evade military patrols or sniper guards.

But freedom brought troubles of another kind. Those who made it, sometimes known as gwihwan dongpo or “returned brothers,” settled in the slums of Seoul, where they faced terrible prejudice—and still do. Even today, almost half of North Korean defectors say they face discrimination in South Korea.

“They called me names, treating me like an idiot, and didn’t pay me as much as others doing the same work, just because I was from the North,” Kwon Chol-nam, who defected in 2014, said in a New York Times piece published this month. “In the North, I may not be rich, but I would better understand people around me and wouldn’t be treated like dirt as I have been in the South.”

Kwon isn’t the only one who wants to return, either. In 2012, a former South Korean MP claimed that already that year more than 100 defectors had gone back, which is about 7 percent the annual number of defectors at the time, and this is despite the fact that upon their return, they could be sent to labor camps where, as one former prisoner told the BBC, people fight over maggots that grow out of corpses and catch rats that they eat raw, “their mouths covered in blood.”

Seoul Tower on Namsan and the neighborhood of Haebangchon below.

When the first wave of “returned brothers” came to Seoul, they settled in the heart of the capital on the southern slope of Namsan, one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods, because it was the cheapest place to live, but also because they had to stick together in order to survive.

Before the war, the neighborhood had been a shooting range for the Imperial Japanese Army, which had its headquarters at the foot of the hill, where the U.S. Yongsan Garrison now sits. According to an historical account of Haebangchon by the neighborhood group Haebangchon Shintaekriji, by the 1950s, it had become home to northern Vietnamese war refugees, a ghetto crammed full of crooked shacks and piles of trash, wooden planks and fragments of asphalt laid over the muddy alleyways, and scrap tires placed on roofs to hold them down in the heavy summer rains. Some people made their homes out of tarp or cardboard, and as one person recounted in the Shintaekriji account, “I could hear the farts next door.”

After the war, Haebangchon, or “Liberation Village,” named after of the community of Vietnamese and North Korean defectors who called it home, slowly began to improve. The roads and back streets were paved, concrete walls replaced cardboard, and metal roofing replaced tarp. But for decades still, its steep, winding alleys and quiet soup shops remained some of the poorest parts of the city.

The 1960 South Korean film Obaltan, or Stray Bullet, is a tragic study in class struggle. Shot in Haebangchon, it depicts the life of a young man, Cheolho, struggling to get by. Considered by many the best South Korean film ever made, its most famous line is repeatedly screamed by Cheolho’s traumatized mother, who survived the war and keeps thinking another attack is imminent: “Get out of here!”

It’s a line that precisely captures the ethos of the community at the time.

Slowly, though, the local economy began to stir. Rolling cigarettes and making sweaters, both labor-intensive work, became the neighborhood’s main industries. The streets were soon suffused with the leathery smell of cheap tobacco and the gentle drone of sewing machines. Still, poverty was rampant. As the Haebangchon Shintaekriji account notes, one resident recalled, “It was like a chicken coop or a barn—my chest got sore every time I saw it.”

The account describes one resident, living in the local schoolhouse, who would walk to the top of Haebangchon, where the quiet Namsan forest began, carefully collect firewood, then cook a ball of unwashed rice—as residents were so poor they feared that by washing the grain, they would lose some small part of it and decided it was better to eat it dirty. Another recalls riding his horse through the woods of Namsan’s slopes and watching children play in the streams there.

Before the war, the neighborhood had been a shooting range for the Imperial Japanese Army, which had its headquarters at the foot of the hill, where the U.S. Yongsan Garrison now sits. According to an historical account of Haebangchon by the neighborhood group Haebangchon Shintaekriji, by the 1950s, it had become home to northern Vietnamese war refugees, a ghetto crammed full of crooked shacks and piles of trash, wooden planks and fragments of asphalt laid over the muddy alleyways, and scrap tires placed on roofs to hold them down in the heavy summer rains. Some people made their homes out of tarp or cardboard, and as one person recounted in the Shintaekriji account, “I could hear the farts next door.”

After the war, Haebangchon, or “Liberation Village,” named after of the community of Vietnamese and North Korean defectors who called it home, slowly began to improve. The roads and back streets were paved, concrete walls replaced cardboard, and metal roofing replaced tarp. But for decades still, its steep, winding alleys and quiet soup shops remained some of the poorest parts of the city.

The 1960 South Korean film Obaltan, or Stray Bullet, is a tragic study in class struggle. Shot in Haebangchon, it depicts the life of a young man, Cheolho, struggling to get by. Considered by many the best South Korean film ever made, its most famous line is repeatedly screamed by Cheolho’s traumatized mother, who survived the war and keeps thinking another attack is imminent: “Get out of here!”

It’s a line that precisely captures the ethos of the community at the time.

Slowly, though, the local economy began to stir. Rolling cigarettes and making sweaters, both labor-intensive work, became the neighborhood’s main industries. The streets were soon suffused with the leathery smell of cheap tobacco and the gentle drone of sewing machines. Still, poverty was rampant. As the Haebangchon Shintaekriji account notes, one resident recalled, “It was like a chicken coop or a barn—my chest got sore every time I saw it.”

The account describes one resident, living in the local schoolhouse, who would walk to the top of Haebangchon, where the quiet Namsan forest began, carefully collect firewood, then cook a ball of unwashed rice—as residents were so poor they feared that by washing the grain, they would lose some small part of it and decided it was better to eat it dirty. Another recalls riding his horse through the woods of Namsan’s slopes and watching children play in the streams there.

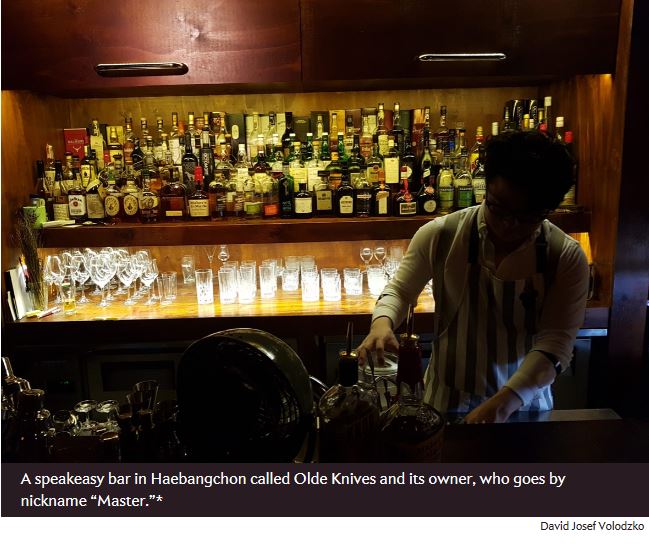

But 62 years later, Haebangchon is now Seoul’s most multicultural and politically progressive pocket, home to a diverse collection of expats, many of whom choose to live there because of its thriving social atmosphere and selection of trendy restaurants. Once full of tobacco shops, laundromats, Korean restaurants, and knitting factories, Liberation Village is now home to retro-style speakeasies, cocktails lounges, artisanal cafés, hipster pubs, a video game parlor, French and Italian bistros, a sex shop, and bookstores with obscure selections curated by celebrity owners.

“In Morocco, I’ve been harassed for wearing jeans and a T-shirt,” says Fatim Zahra Boushit, a 26-year-old bartender. “But I can do anything I want here, date whoever I want, dress the way I want, show skin, and I don’t get catcalled. Back home, you get catcalled even if you’re in niqab.”

“I feel comfortable here because I don’t have to explain myself.” Fatim Zahra Boushit

She shakes her head as she pulls the beer tap to pour another drink.

“I feel comfortable here, because I don’t have to explain myself.”

“You can easily hang out and make friends with people from different backgrounds,” says Aimable NiyiKiza, a 26-year-old Rwandan cybersecurity engineer who moved to Haebangchon in March 2016. Tegegn Yimer Kassa, a 35-year-old Ethiopian who teaches taekwondo and hapkido, moved there in 2013 and says he enjoys the diversity and the fact that “it’s very close to Namsan for walking, and the view there is very natural.”

In the days before plumbing, Koreans ghettoes were usually situated on hilltops, where residents had to suffer the daily work of carrying water buckets up to their homes. These neighborhoods were known as daldongne, or “moontowns,” because they seemed however slightly closer to the moon, propped upon a hill. Haebangchon’s hill is Namsan, and over the years, Namsan forest has changed considerably as well. It’s now replete with hiking trails, water gardens, forest boardwalks, and a view of the neon skyline from Seoul Tower. But, Kassa adds, the neighborhood is not without its drawbacks. “On the weekend drunk people make noise, the traffic can be uncomfortable, and there are too many smokers disturbing the public.”

Haebangchon’s growing popularity means some restaurants have lines that snake around the block, bars crowds often spill out onto the pavement, and cars park illegally along the street, forcing pedestrians to share the road with mountain bikers descending Namsan and the occasional Lamborghini as it barrels through, driven by a celebrity who trusts he or she can relax here without being recognized. But there’s another, more harmful effect. Naqash Kham, a 25-year-old Pakistani who moved to Korea in April 2016 to get his masters in international business, says it’s good to see new people moving into the neighborhood “because they’re trying to survive,” but says he doesn’t like seeing older Koreans pushed out.

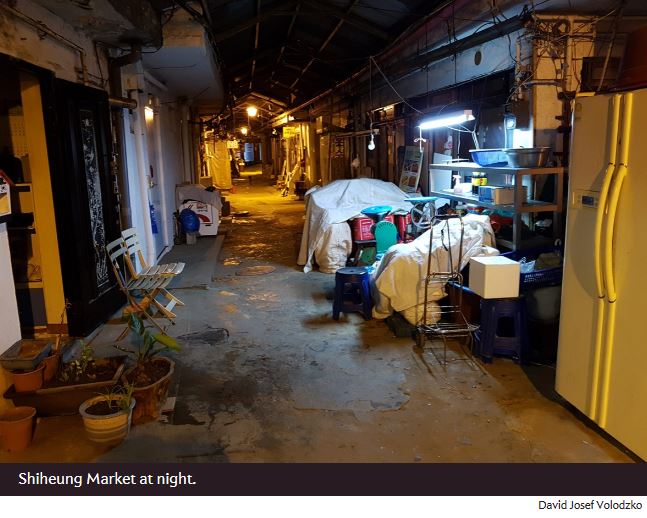

However, the Seoul Metropolitan Government is encouraging Haebangchon’s quickly changing demographic. In 2014, the city announced plans to spend 10 billion won (U.S. $8.56 million) over the next five years to revive the area. One plan is to renovate Shinheung Market, once a thriving city center near one of the city’s busiest streets, Shinheung Road, now Haebangchon’s main drag. Knitting factories sold their goods at the market in the ’60s and ’70s, but business has dried up, and the now government wants to turn it into an open-air art bazaar. Many local artists welcome the change, while others see it as another form of gentrification.

Another plan is to update the iconic 108 Stairway. In the blog Korea Exposé, Haeryung Kang writes about the fascinating history behind this often ignored landmark, a staircase that once lead to Gyeongseong Hoguk Shrine, built in 1943, where Japanese colonialists forced Korean schoolchildren to attend daily prayers honoring Japan’s war dead. All that remains now is the stairway. The Yongsan District Office, Kang reports, is planning to build a “facility for convenient movement” right on top of the stairway, which could mean an escalator, elevator, or funicular. Kang notes how the Japanese Government General Building, an elegant neoclassical structure in central Seoul, was torn down in 1995, and asks, “Is there value to remembering a painful past? What are the consequences of repressing or forgetting it?”

The neighborhood’s North Koreans are already all but gone, save for a few noodle shops and the odd sewing store, and soon, Shinheung Market and the 108 Stairway may soon join them. While a few, like Daniel Park, keep some of its history alive, Haebangchon continues to change. Today, it’s a multiethnic mecca totally at odds with the city that surrounds it yet one that draws increasing numbers of young Koreans. And though the past is quickly being lost, the struggle that began so long ago, the struggle to make this a village of liberation, is slowly being won.

Correction, Aug. 22, 2017: Due to a production error, this photograph’s caption originally identified the image as Fatim Zahra Boushit bartending at the Hidden Cellar in Haebangchon. The photo is actually of a speakeasy bar in Haebangchon called Olde Knives and its owner, who goes by nickname “Master.”*

(Source: http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/roads/2017/08/life_in_haebangchon_seoul_s_transforming_little_pyongyang_neighborhood.html)