What makes a megacity sustainable

Introduction

In a recent academic review of megacity literature, Sorensen and Okata (2011) state that “in a profound sense, megacities are inherently unsustainable, with their vast consumption of resources drawn from distant “elsewheres” and their equally vast production of wastes that are routinely exported elsewhere.” They conclude the paragraph by referring to Satterthwaite’s (1997, citied in Sorensen and Okata, 2011) suggestion that “the goal is....not sustainable cities per se, but cities that contribute to sustainable development.”

This view of the concept of the “sustainable megacity” has implications, which are pertinent to the discussion of Seoul’s transformation from a megacity with its overwhelming burden of rapid expansion into what might be, arguably, referred to as a “smart megacity”. Quite importantly, the notion of the smart city inevitably involves the attributes of sustainable development, which will be addressed in a later section of this paper. Is it really the case that megacities are inherently unsustainable? Is the “sustainable megacity” an oxymoron? How about the “smart megacity?” Can a megacity be a smart city? Here, should the goal be to establish a city that contributes to smart development, rather than the smart city itself being the definitive outcome?

It may be futile to debate whether a city is sustainable, or smart for that matter, in any definitive sense. However, it is relatively straightforward to determine whether an attribute of the collective endeavors undertaken in a city contributes to sustainable development or smart-city building. Similarly, it would be relatively easy to see if several different types of attributes of public action results in greater sustainability or smarter development when presented in a city simultaneously, or better yet, when integrated as a coherent system. It would then be an extremely constructive exercise to identify such a set of collective endeavors in any city with a view to drawing lessons or transferring proven know-hows to other contexts where such a contribution to sustainable or smart development is greatly needed from the global perspective.

Before exploring what makes a smart megacity or what might contribute to sustainable development, it would be helpful to discuss what these adjectives signify and how the global urban community came to these popular ideas about the contemporary city and what they indicate.

What it is vs. what it aspires to be – Different uses of city descriptors

Modern geographers (in human geography) were primarily concerned with the growth and development of cities, and sought to answer such questions as to why cities are where they are; or what makes a city grow or decline. Similarly, for urban economists, the most commonly used city classification criterion was the size of a city—with the classes being almost entirely limited to small, medium and large—as one of the basic hypotheses in urban economics was that the nature and size of agglomeration benefits or other economically significant phenomena are associated with a city’s size.

Urban planners in early modern times were a somewhat different breed, primarily in terms of their approach to the investigation of cities, from empiricists who examined cities on the basis of evidence, such as economists to early human geographers. Planners largely came from the tradition of design, hence, of imagination and creativity. Early urban planners would therefore be concerned with prescribing what things ought to be like (representing the “normative” perspective), whereas empiricists were primarily concerned with how things are (representing the “positive” perspective). As such, urban planners have continued to propose various models of the ideal city. Some of the city descriptors that we are familiar with today, including “sustainable,” “resilient,” or “smart” may be seen in the tradition of this normative perspective, that is to say that “sustainable” or “smart” are a kind of a state which a city might aspire to become. These abstract and value-based names are, therefore, different from a descriptor which is attached to some cities, because they are already what they are.

For instance, descriptors such as “small,” “large,” “port” or “historic” merely describe and characterize a city in a positive manner, whereas the words “sustainable” or “smart” indicate a character or a value that a city might aspire to possess as a central character or a representative value in a “normative” sense. When a city does possess and exhibit the key attributes of the core value and becomes an embodiment of that value, however, the descriptor then plays a descriptive role as well. Therefore, many cities would call themselves a creative city, for instance, when they would like to be one. But there may be a much smaller number of cities that are acknowledged as such by the rest of the world. The same ambivalence in naming a city applies to other value-based descriptors such as “sustainable,” “smart,” “resilient,” “livable,” “healthy” or “eco” city.

The rise and fall of great cities

City descriptors with normative connotations such as creative or culture became fashionable with the emergence of urban entrepreneurialism and city marketing around the 1980s, although largely in the Western part of the world. That was when industrial cities, whose past prosperity and wealth was largely accumulated on the basis of manufacturing, proactively sought ways of recovering their greatness by attracting different sorts of activities, such as cultural or creative ones, as they underwent the process of deindustrialization. In this context, place rebranding and city marketing were seen as modes of urban regeneration and competitiveness building. Hence, cities, or municipal governments, began to see their role as an entrepreneur rather than as a manager.

In contemporary terms, great cities must have the status as a world city. A great deal of research has been undertaken to define, describe and theorize the world cities phenomenon, but it is still subject to debate as to which cities make the list. Amongst a few widely known world city scholars, however, there is no one who has denied the world-class city status of New York, London, Paris, or Tokyo (Friedmann 1986; Sassen 1991; Know and Taylor 1995). Amsterdam is often included too. So are Seoul and Sao Paulo. Some scholars have published a more generous list including a few megacities in developing countries (Lo and Yeung 1996). The world city discourse is now somewhat dated, so the rapidly emerging, globally important great cities of China did not figure in the classic world city discussions, for instance. The most consistent criterion to assess the world-class city status of a city is to ask whether the decisions made in that city influence actions in the rest of the world, and to what extent does such a city exert its influence over other cities in the world, if indeed it does.

Economic dynamism is likely at the core of any great city. It is the magnetic power that continues to attract people, but it comes with strings attached in all known cases. The great cities of today and of the past alike have had their own big share of problems. This combination of great problems with great cities was seen as inevitable.

Ever since cities emerged in history, especially after they grew large with the help of transportation technology that evolved over time, cities have been seen as a source of opportunities and problems at the same time. What defines a city is simply the size of the population who live there. If an area can be visibly distinguished from its surrounding areas due to the population concentration, and the number of people living there exceeds a certain administratively determined threshold, it is defined as a city.

This concentration of people creates opportunities which are not available outside the area of concentration, but concentration inevitably means magnified conflicts and contests. Both agglomeration benefits and negative externalities (the secondary, unintended effects of what we do to live) exist in great quantities in great cities.

The industrial cities largely located in the West shared virtually the same set of urban problems: congestion (people and vehicular traffic), environmental pollution, decline of the city center, slums, homelessness, safety, public health, spatial segregation/disparity, high impact disasters due to occurring in an area with a dense population, and so on.

These consequences of industrialization and urban expansion aside, great cities in the world have enjoyed the prosperity they achieved, their popularity (or magnetism), and their status of being great. If, however, the problems grow out of proportion and eventually outweigh the attractiveness of the city, it ceases to be great, as seen in many industrial cities in the West. These cities had to undergo what is now commonly known as urban regeneration in order to recover their greatness. The key here lies in keeping the level of nuisance in check.

A move towards not-so-great cities: quality rather than quantity

Garden Cities

Throughout history, urban thinkers have proposed various models of a city in which human interactions are accommodated on the urban scale but, through design, excessive urban predicaments are minimized or even prevented. Early thinkers tended to focus on the balance between town and country; or the harmony between the built environment and the natural environment. This would be done by placing sufficient green areas – buffers – within the city as a way of mitigating harsh urban environments and the problems habitually associated with harsh and hard surfaces. Howard’s Garden City (1902) is probably the best known among these models and has had an enduring influence on subsequently proposed notions of urban planning along an extensive time spectrum, ranging from Howard’s own contemporary, namely Raymond Unwin and his Garden Suburb and the British planning tradition ranging from “greenbelt” and “New Town” to the “New Urbanism” movement of late.

Sustainable towns and cities

2) High density: At least 15,000 people per km², i.e. 150 people/ha or 61 people/acre.

3) Mixed land-use: At least 40 percent of floor space should be allocated for economic use in any neighborhood.

4) Social mix: The availability of houses in different price ranges and tenures in any given neighborhood to accommodate different incomes; 20 to 50 percent of the residential floor area should be set aside for low cost housing; and each type of tenure should be no more than 50 percent of the total.

5) Limited land-use specialization: This is to limit single function blocks or neighborhoods; single function blocks should cover less than 10 percent of any neighborhood (2014)”.

Even though there is no mention of green space in this UN HABITAT description, it is hard to doubt that, in anyone’s imagination, the picture of a sustainable town or city includes abundant shades of green. As such, the physical structure or appearance of sustainable cities might share common characteristics with that of the Garden City. However, as can be seen in the above five principles suggested by UN HABITAT, the focus here with regard to sustainable towns and cities is on the ecological impact of urbanization.

The crucial difference between Howard’s Garden City and the sustainable city is that environmentalism lies at the core of the contemporary idea of sustainable cities. This would also mean that the shared goal is to achieve sustainability on the global scale and not just at the individual city level. The global community is more conscious than ever of the implications of what shape of development path an individual city follows. Prosperity may be achieved at an individual city level, but the often environmentally damaging impacts of a city’s prosperity are shared by all.

The wide diffusion of the sustainability concept, as well as its influence over nearly every aspect of collective actions that are undertaken in cities around the world, shows how our values and preferences have evolved over time. There probably are, among cities and people, those who prefer not-so-great cities – especially in terms of their physical size (of input and output; of population, land and productivity) and the size of negative externalities. The emergence and presence of sustainability as an overarching concept over the past quarter of a century suggests that our aspiration for greatness in terms of population and economic output is being replaced, at least in part, by the aspiration for cities with a low ecological impact. The variety of names for an ideal city that has penetrated into our day-to-day conversation as well as into academic discourse, such as sustainable cities, eco-cities and livable cities, and the intensity of the influence these concepts have on current urban practices might well indicate our contemporaries’ greater concern for quality rather than quantity.

Resilient Cities

More recently, however, “sustainable” has not seemed to be good enough or as fashionable as it had been until a decade ago, and the new buzzword has arguably become “resilient” in the core urban discourse. Leaving aside the purely equilibrium-focused viewpoint, a more inclusive definition of resilience that is useful for urban planning refers to “the ability of a system to adapt and adjust to changing internal or external processes (Holling, 1973; Gunderson et al, 1995; Pickett et al, 2004).”

According to a widely accepted definition of resiliency in cities, a locale is resilient if “it is able to withstand an extreme natural event without suffering devastating losses, damage, diminished productivity, or quality of life and without (receiving) a large amount of assistance from outside the community (Mileti, 1999, pp. 32–33).”

The Smart City

Whilst “resilient” does not really seem to have gained traction outside academia, “smart” has indeed attracted considerable attention from governments in both the developing and the developed world, although the reaction appears to be more pronounced in the former. In fact, it was global technology firms that were responsible for the particularly rapid spread of this new “brand” of city (Holland 2014).

As such, the smart city is often associated with a “technological fix” or an attempt to resolve all types of urban problems through technology. A more useful and sensible definition of the smart city, however, refers to a city which is “more economically prosperous, equal, more efficiently governed and less environmentally wasteful” (Holland 2014), and it does not necessarily prescribe how to reach that state of a city, suggesting that the “question of how” is open to new ideas or innovations, be it through technological innovation, innovative use of existing technology or simply new ways of doing things as long as the new inputs and processes can bring about different outcomes from business as usual.

It is more commonly linked to such ideas as “doing more with less”; growing positively with fewer social costs; and, at the same time, responding to diverse human needs, demands and values. The emphases on diversity and inclusivity call for the ability of the city to coordinate and integrate different facets of municipal affairs, domains and goals.

Comparing contemporary ideas of a desirable city: Similarities and differences

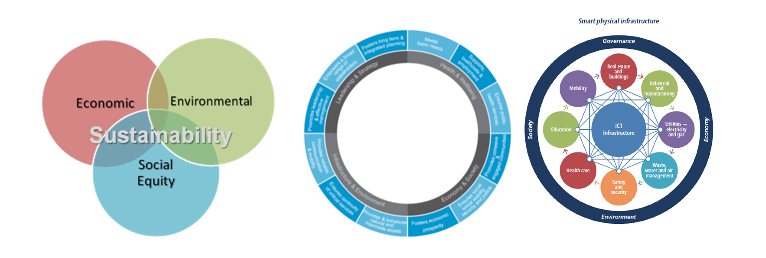

Figure 1. Conceptual diagrams representing the three models of city: sustainable, resilient, and smart

Sources: http://www.ci.neenah.wi.us/departments/sustainable-neenah-committee; http://www.100resilientcities.org/resilience#/-_/; https://itunews.itu.int/en/About.aspx

These three contemporary notions represent leading values of our time in the realm of city making. The three alternative models, however, share the following common objectives:

1) To make materialistic progress with less social or environmental harm.

2) To maintain a balance between the three competing values – economic, social, and environmental.

The differences are rather subtle and may be characterized as follows:

- Sustainable: Slow economic growth is allowed, tolerated, or (possibly) preferred for the sustainability of both society and the environment.

- Resilient: Preparedness for (future) challenges is highlighted and may come from various quarters (planning, leadership, etc.), but economic power as the source of resilience is crucial. Resilient cities are more proactive than sustainable cities.

- Smart: Cities in this category might seek a third way of doing business to maximize materialistic prosperity and address all negative impacts on non-materialistic values through some innovative, “smart” means. It is as if they were asking the question: Is it even possible at all not to compromise the materialistic potential while ensuring the protection of non-materialistic values? Smart cities might be the most proactive and ambitious among the three notions of city.

If we agree with these inexplicit differences between different names or brands of city, it is scarcely surprising that the idea of smart city or smart development appeals to rapidly growing cities in the developing world, which are faced with the need to increase their materialistic wellbeing while addressing or preventing the foreseeable consequences of rapid development. It does feel that the smart city promises greater prosperity than the “sustainable or resilient cities,” to which the developing countries are bound to aspire most.

Despite the similarities discussed earlier, the audience of contemporary urban discourse seems to have its own perceptions about alternative notions which are generally shared. For instance, cities such as Curitiba, Freiburg, Copenhagen and Mälmo are frequently cited with the sustainable label attached to them, whereas a different set of cities such as Singapore, Seoul and Amsterdam are more often referred to as smart cities.

Nevertheless, it is quite clear that sustainability as a value and its practical implications are embodied in the smart city model. In other words, a city which is not environmentally or socially sustainable cannot become a smart city. Likewise, a city which is not resilient and is unable to withstand external threats cannot be considered a smart city, or a sustainable city for that matter. Attempts to link resilience and sustainability have also been made, though they may not be particularly inventive given the objectives and values shared in large part by the two ideas (Asprone and Manfredi 2015).

After all, these three models represent the values and objectives that contemporary as well as future cities would aim to achieve. Given that these models share similar values and the objectives do overlap across all three of them, it might not be a particularly fruitful exercise to discern between them. The analysis above suggests that smart cities could embody the attributes of both sustainable and resilient cities and, in addition, they are thought to cater to a more proactive approach to development. It might be sensible to adopt a more, albeit marginally, inclusive concept and ensure that all the core values subscribed to by the three notions are well covered.

A glance at Seoul

“Korea has experienced remarkable success in combining rapid economic growth with significant reductions in poverty. The government of Korea’s policies resulted in real GDP growth averaging 10 percent annually between 1962 and 1994. …. Korea is the first former aid recipient to become a member of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). …. Korea's experience in sustainable development, providing infrastructure and better services to improve the lives of the people, and its transition to a dynamic knowledge economy, provides lessons that can benefit many other developing countries.” (The World Bank 2015)

As illustrated in this paragraph, the dramatic economic transformation that Korea has achieved just in 60 years since the Korean War is relatively well known. What is less widely known is how it has been addressing the undesirable impacts of exceedingly rapid urban transition and equally rapid industrialization; how the country has made concerted efforts to promote spatial and social equity, for instance, by reducing regional disparities in development and rural-urban differentials in terms of the opportunities and the quality of life which accompanied the spectacular expansion of the wealth of the nation. In effect, Korea’s transformation has not been limited to the economic realm but has also permeated into other realms, which are currently valued just as much, including the environment and society.

Clearly, Seoul has been at the center of transformation which the country as a whole has gone through. As the greatest contributor to national economic growth, the city has undergone even faster growth in terms of population and activities, and therefore had a greater share of the impacts generated by rapid development. Just as the country has been making various attempts to address the consequences of rapid development, the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) has continually endeavored to deal with the undesirable outcomes of the extraordinary growth it has achieved within an extremely short span of time. Years of such strenuous efforts have begun to show signs of transformation from the previously quantity-driven, pro-development industrial city into a so-called smart city, or a city that regularly crops up on the list of exemplary cities in some specific senses, such as a city with a smart transport system or a superior e-governance system.

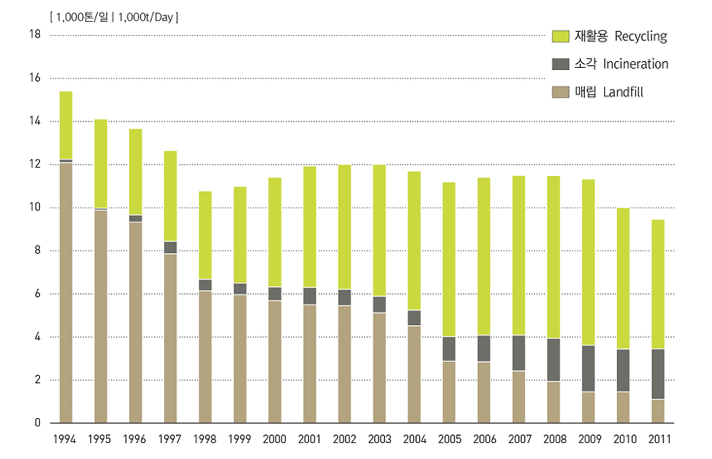

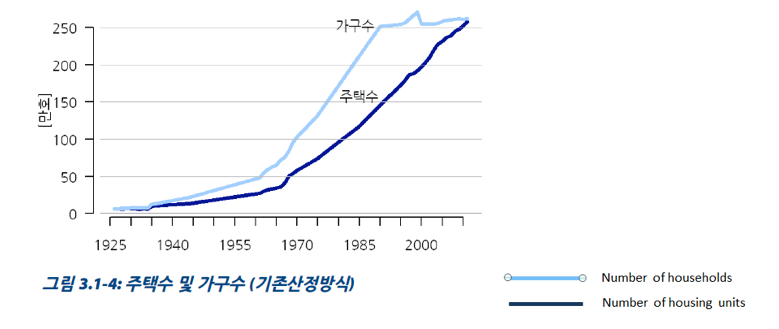

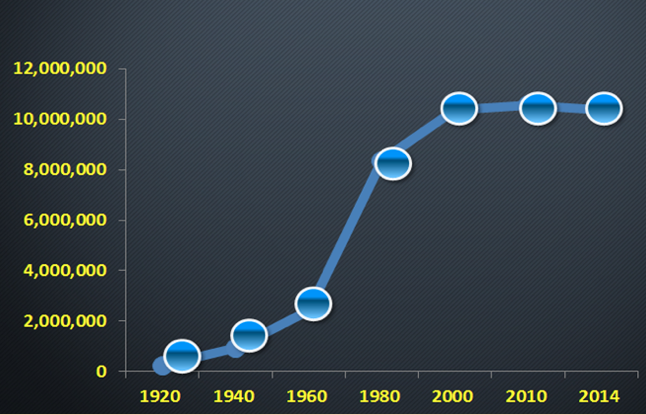

The sets of statistics (Figure 2 – 4) given below might give an idea of the extent to which some of the acute urban problems facing most fast growing cities have been dealt with in Seoul.

Figure 2. The share of sustainable transport modes in Seoul

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government (2015)

Figure 3. Trends in the number of households and the number of housing units

Source: Seoul Statistics Yearbook 2000, cited in Seoul Institute (2003)

Figure 5. Percentage of people recycling in selected cities, 2011

Size matters and so does speed: Dealing with mega-size urban problems in a short span of time

First, Seoul is quite different from other oft-cited sustainable or smart cities in terms of size. How many megacities in the world are also representative of the sustainable city? It is also one of the few sustainable or smart cities to have emerged from the developing world to which it still belonged not so long ago. How many of the megacities which used to represent a city paying the price of hyper-urbanization and super-fast industrialization until about twenty years ago have turned into one of the few cities representing the highest rates of recycling in the world? All of the recycling cities included in the previous figure come from the traditional first world (or countries which completed their industrialization by the early 1960s) except Seoul.

Megacities are thus called because they exceed certain thresholds in terms of population size, and for no other reason—with the caveat that the threshold is something of a moving target as the cities in the world generally grew further and faster with time.

The difference in size means the scale of the problem is conspicuously different. It may help to be reminded of the quote that appeared at the start of this paper: “…megacities are inherently unsustainable, with their vast consumption of resources drawn from distant “elsewheres,” and their equally vast production of wastes that are routinely exported elsewhere (Sorensen and Okata (2011).”

Figure 5. Seoul’s population growth over time, 1920-2014

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government

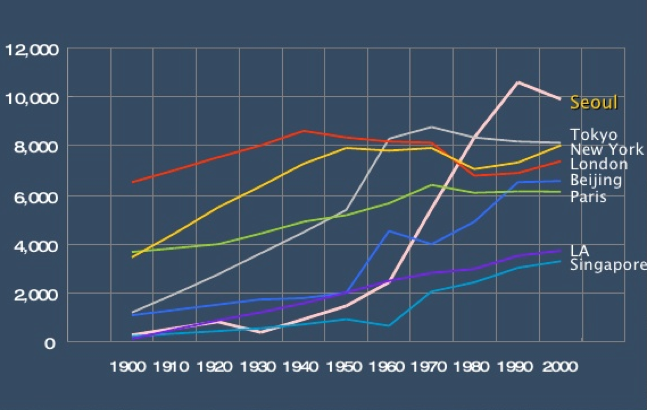

The size and rate of Seoul’s growth over the past century is compared with a few other world cities in Figure 6. Singapore, a city that is as often referred to as a smart city, is also included in the graph. Seoul’s steep population growth between 1960 and 1990 clearly stands out from the rest of the city group illustrated.

Figure 6. Population growth rates, 1900-2000, for selected cities

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government

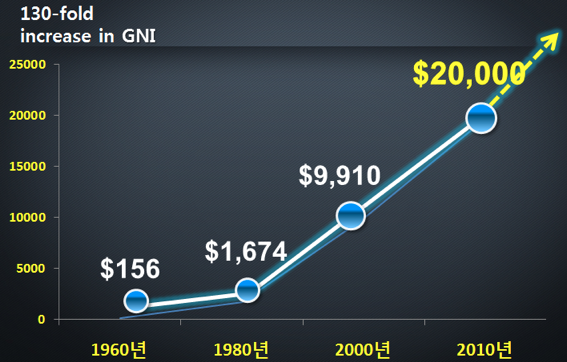

Figure 7. Economic growth rates in Seoul, 1960-2010

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government

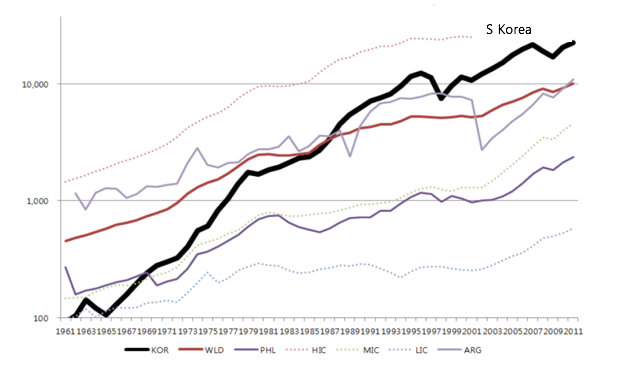

Figure 8. The rate of economic growths, 1961-2011, selected countries

Source: The World Bank (2010)

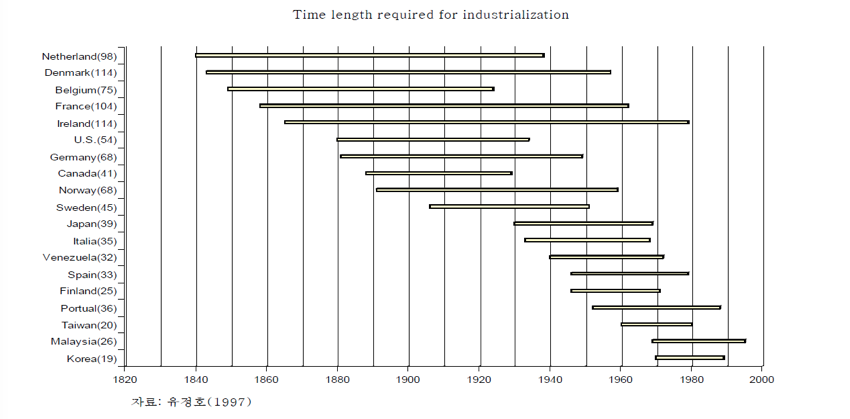

As a matter of empirical fact, the time taken for industrialization has increasingly lessened over the centuries behind us, as Figure 9 illustrates. This is not because newly industrializing countries have been more able than their predecessors, but rather because of the greatly enlarged world market.

Figure 9. Time taken for industrialization for selected countries

Source: Yoo (1997)

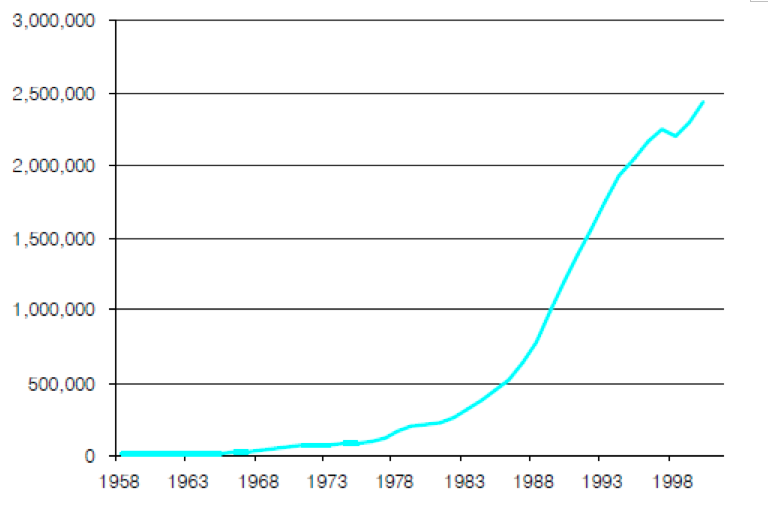

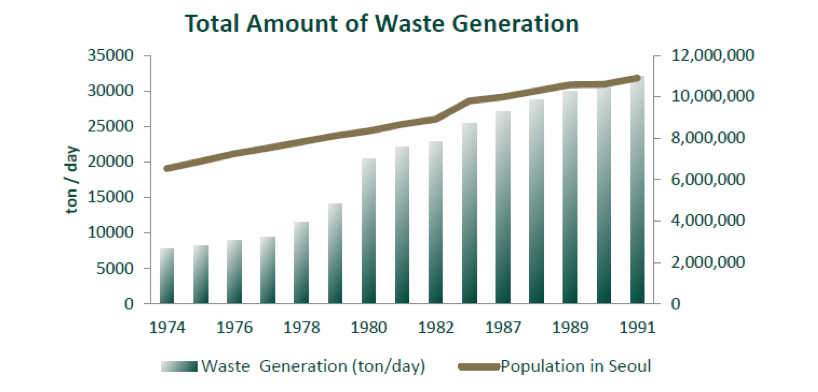

The successful urban management of Seoul ought to be looked at from the context of the exceedingly rapid changes that occurred in the city. At such rates of growth, the magnitude of urban problems is normally overwhelming and continues to grow at an alarming rate in the absence of appropriate intervention, as has been the case in numerous megacities in the developing world. The following pair of illustrations (Figure 10-11) will give perspective on how Seoul has been faced with some of the negative externalities of rapid urban expansion most frequently associated with megacities.

Figure 10. Increases in the number of motorized vehicles in Seoul, 1958-1988

Source: Seoul Statistics Yearbook 2000, cited in Seoul Institute (2003)

Figure 11. Increases in waste generation in Seoul

Source: Ministry of Environment cited in Seoulsolution 2014, Recycling (Smart Waste Management in Seoul)

Negative externalities are not necessarily proportional to population and economic growth

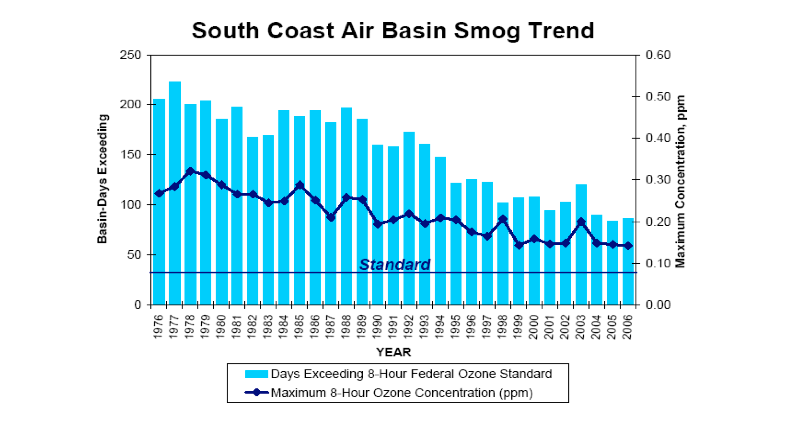

Are negative externalities proportional to growth in a city’s population and economy? History seems to suggest that they are not. The City of Los Angeles and its surrounding areas long suffered from urban smog associated with high atmospheric ozone levels. The basin-like topography, abundant sunlight and low mixing heights resulting from the marine layer all work against atmospheric air quality in Los Angeles, and the city has been growing fast compared to other leading cities in the country. Despite these natural characteristics and urban indicators, ozone levels have been decreasing over the past few decades while the city’s population and economy, as well as the number of vehicles in the area, have continued to grow (Figure 12).

The decrease that began in the mid-1970s is not a coincidence. It was in that decade that a set of very aggressive policy measures were adopted by the city to reduce emissions from various sources including automobiles, a key contributor to urban ozone levels. Los Angeles clearly illustrates the ability of public policies in changing the nature of the relationship between growth and growth-related negative externalities.

Figure 12. Ozone levels over time, Los Angeles

Source: South Coast Air Quality Management District (2007)

Trends in social costs of rapid growth in Seoul

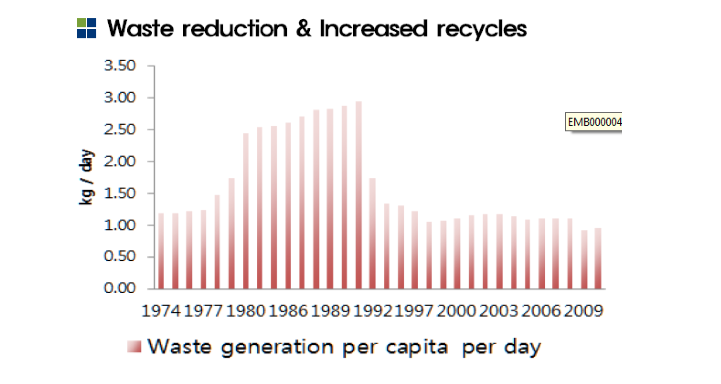

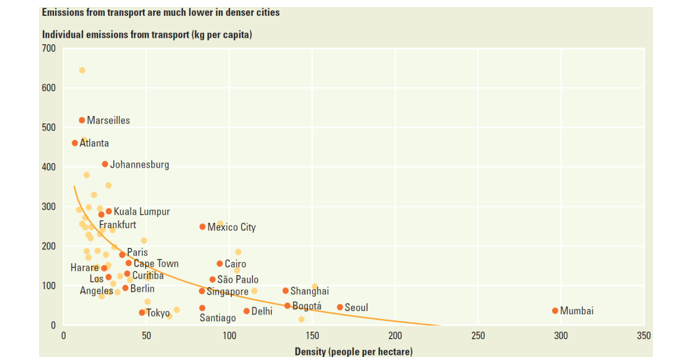

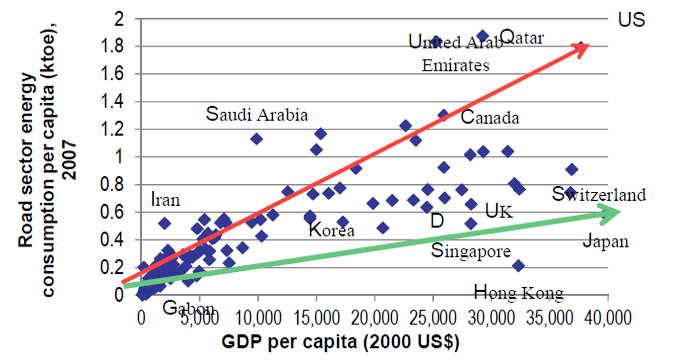

In the absence of an established set of sustainability or smart city indicators, a set of measures that are often used to represent sustainable or smart growth—including energy efficiency, emission rates, waste discharge and efficiencies in land consumption—are considered below in an attempt to appraise the state of urban management in Seoul (Figure 13-15).

Figure 13. Waste generation per person

Source: Ministry of Environment, cited in Seoulsolution 2014, Recycling (Smart Waste Management in Seoul)

Figure 14. Transport-related emissions per person

Source: World Bank 2009

Figure 15. Energy (road sector) consumption and GDP

Source: World Bank (2014)

In the absence of an established set of sustainability or smart city indicators, a set of measures that are often used to represent sustainable or smart growth—including energy efficiency, emission rates, waste discharge and efficiencies in land consumption—are considered below in an attempt to appraise the state of urban management in Seoul (Figure 13-15).

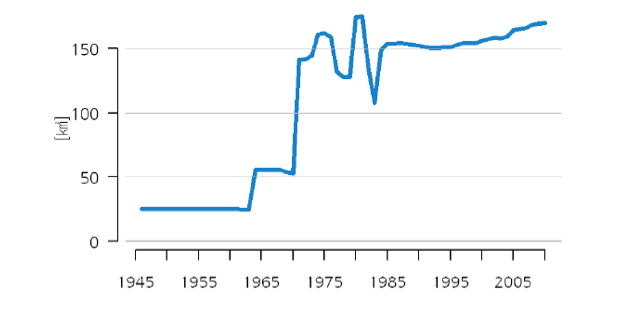

Figure 16. Trends in the size of green areas (km2)

Source: Seoul Statistics Yearbook 2000, cited in Seoul Institute (2010)

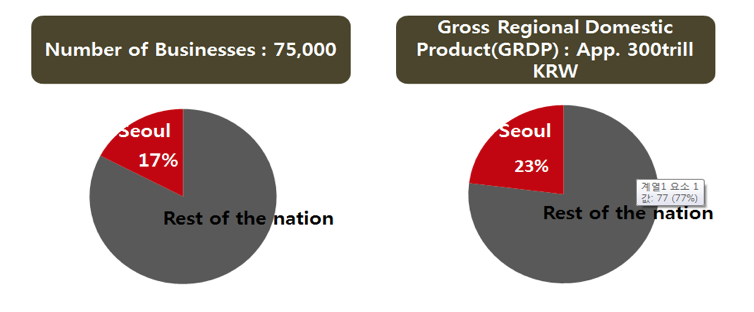

Figure 17. The intensity of economic activities in Seoul

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government 2015

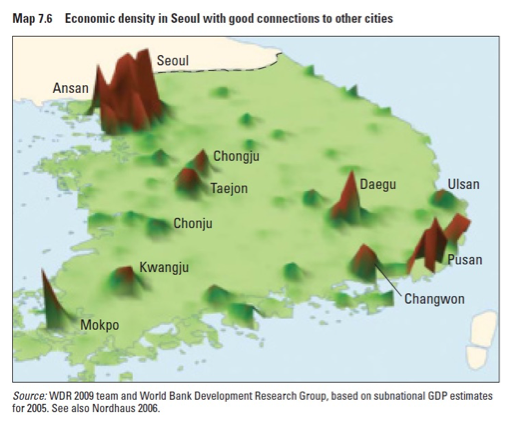

Yet the country has managed to develop a relatively healthy urban hierarchy, unlike some other countries marked by the presence of an overwhelming primate city, a trait often associated with developing countries (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Korea’s economic density map

Figure 18. Korea’s economic density map

Source: World Bank (2009)

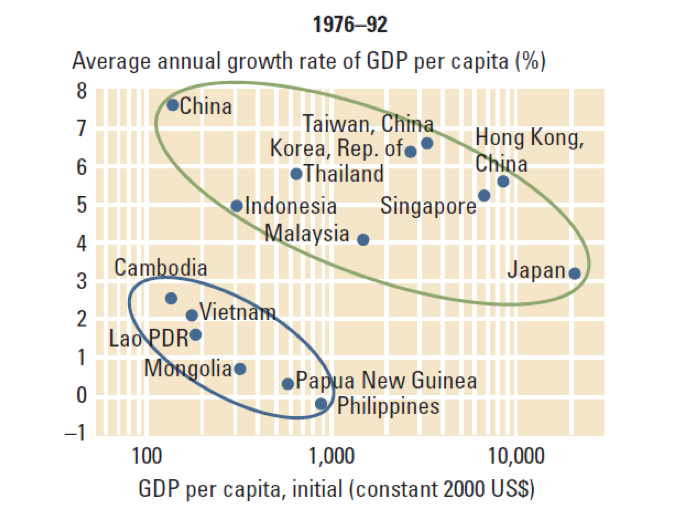

Figure 19. GDP growth rates and income levels

Source: World Bank (2007)

What has enabled the successful urban management in Seoul?

Is it the high density that made the smart transition possible? Indeed, Seoul’s urban density is among the highest in the world. The city has thousands of high-rise apartment buildings, which house a very large proportion of the residential population. This pattern of housing is followed up even in the new towns that have been developed away from Seoul in an attempt to redistribute the city’s over-concentrated population. There is no doubt that such population density contributes to the smart use of land and energy resources, as the two previous illustrations aptly demonstrate.

Or is it the public resources made available to the city that have been the key to the successful management of the city? Perhaps, the city did make smart use of what was available in terms of financial resources in building up the infrastructure it needed to accommodate its ever expanding population and activities. Korea is known for its effective and well-established public investment management system, which means an equal amount of financial resources could well have resulted in a greater amount and higher quality of public infrastructure than in a country without such a system.

As such, both urban density and public resources (and their efficient use) have their place in the explanation of Seoul’s achievements in urban management. By no means, however, are they sufficient conditions for making a city smart, as not all megacities with comparable, or even higher, densities (such as Manila) or megacities with comparable levels of resources (such as some Latin American cities) have shown similar trends in managing their urban problems.

The explanations will inevitably have to be more complex than what can be covered in this brief discussion. Subsequent discussions, therefore, will help explain the contexts, planning and implementation processes, governance, political climate or founding infrastructures in different but relevant policy domains.

What can be highlighted here is that Seoul’s success in urban management clearly exemplifies the ability, or even the power, of public policy, as seen in the earlier example of Los Angeles. The SMG proactively and persistently implemented a set of policies aimed at addressing the key urban problems to which all rapid developers would be doomed without appropriate intervention of some form. The secret also lies in selecting and prioritizing among competing needs and domains of policy, for public resources are ultimately finite regardless of the income level of the city. The selection was not dictated by any high moral values, however, but rather by practical needs and implications.

For instance, without the smooth circulation of people and goods, the life of the city’s inhabitants and the city economy would suffer, if not reach an impasse, even if some other excellent policies seeking to promote equality in the city or the quality of local residents’ life were adopted and implemented. This probably is where Seoul has been successful, i.e. reaching a consensus in the setting of priorities.

But what has the city actually done in practical terms? In a nutshell, the city has developed a coherent and practical institutional framework that ensures the implementation of a given policy and the attainment of the policy goals for each policy area, often backed with comprehensive data of pointed relevance, state-of-the-art technology, and the best available knowledge sourced by teams of highly qualified quality researchers and officials; and, where needed, it has streamlined the relevant institutional framework (including the enactment of special laws, if necessary).

While these policies were developed within a coherent strategic framework, each policy initiative was in fact developed as an individual building block. Initially, these were designed and implemented separately, but when they were all completed at least in phases, they then made sense as a whole.

The highlights

Transport

Seoul’s transport system addresses the two quintessential transport issues, accessibility and mobility. High degrees of accessibility have been achieved by establishing one of the world’s most convenient public transport networks, and one that is within easy reach of most of the city’s inhabitants. Decent levels of mobility for the city’s size are provided through the balance between the extensive road network and the truly integrated public transit system, the popularity of which ensures that the number of motor vehicles on the road is kept in check. Information and communication technology including big data played a significant role in the construction of Seoul’s smooth circulation and accessible transport, including the integrated monitoring system, Seoul TOPIS (Transport Operation and Information System) and the development of the ingenious nighttime hour bus service network, Night Owl Bus.

Another key component of the transport policy package includes the 2004 Bus Reform, which enabled Seoul’s transit system to become truly integrated by combining all four elements of transit integration, namely, service integration, fare integration, interchange facilities, and information. A set of travel demand management measures is also in place, and a built environment conducive to soft measures such as walking and cycling is under development, both of which will contribute to guiding the travel behavior of citizens over the longer term.

E-governance

On numerous occasions, Seoul has been ranked first in terms of e-governance performance when assessed. The following table shows the results of an international research initiative on municipal e-governance (Table 1). The survey by Rutgers University identified Seoul as the best performer in various categories, such as usability, service and citizen participation.

Table 1. Global e-Governance Survey Ranking

| Ranking | City | Score |

| 1 | Seoul | 84.74 |

| 2 | Prague | 72.84 |

| 3 | Hong Kong | 62.83 |

| 4 | New York | 61.1 |

| 5 | Singapore | 58.81 |

| 6 | Madrid | 57.41 |

| 7 | Vienna | 55.59 |

Source: Rutgers University 2009, cited in Choi 2014.

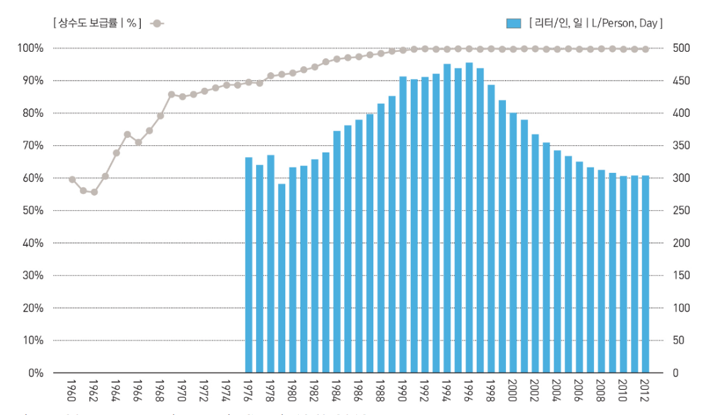

Waterworks

In the decade or so after the project to develop a reliable water supply network was launched, the water service rate exceeded 90% before it began to cover the entire city population. This all happened while the city continued to grow. In so doing, the city developed new financing mechanisms such as OECF loans, local bonds and foreign loans to address the funding challenges. Another factor contributing to consistent policy development and implementation has been the establishment of an independent agency in charge of governing the water in the city, the Seoul Waterworks Authority, in 1989. Both the RWR and water quality have been consistently showing an impressive upward trend, thus reflecting the benefits of specialized management and institutional rearrangement.

Figure 20, Water supply rates in Seoul, 1960-2012

Source: Seoul Statistics

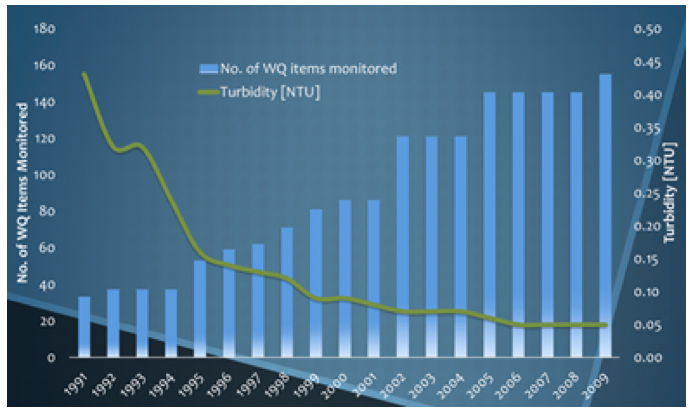

Figure 21. The number of water quality monitoring items and the turbidity of the treated water

Waste Management

Figure 22. Changes in waste generation and waste treatment methods, 1994-2011

Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government 2016, https://seoulsolution.kr/ko/seoul-map

Transferability of the policy platforms

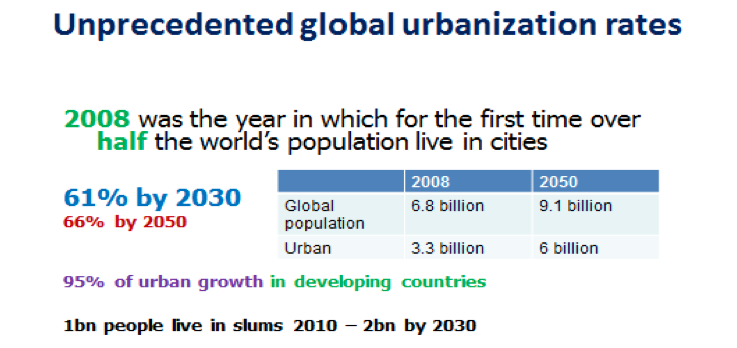

The year 2008 marked a watershed in that, for the first time, over half of the world’s population lived in cities. Furthermore, the proportion of urban population will increase to two-thirds of the global population by 2050—only 34 years later. In other words, 6 billion out of 9.1 billion people will live in cities. What is more striking is that 95% of that urban expansion will take place in developing countries.

Figure 20. Global urbanization projection

Source: UNHABITAT (2009)

Concluding thoughts

It is not entirely clear whether this is primarily due to the ubiquity of technological applications in Seoul that the city has been referred to as a smart city. What Seoul has achieved is not limited to the active application of advanced information technology in the area of city management as seen in this discussion. Indeed, Seoul also utilizes technology, and information and communication technology in particular, to diagnose problems and prescribe solutions where needed, but does not utterly rely on technology. Nevertheless, the successful implementation of Seoul’s urban policies is often associated with the effective use of data infrastructures which support and enable a systemic approach to urban solutions in such areas as land registry, waterworks, transport, safety, disaster, and so on.

In reflecting upon what has made it possible for Seoul to build such a centralized system of urban data, one may question or even challenge the top-down approach that has been taken to build such systems of operation and monitoring.

Bottom-up, voluntary rules and political participation are all very well, but in reality it truly is a question worth contemplating if super-rapid developers like South Korea can afford the time needed to form a voluntary consensus and then construct systems that work as efficiently as those Seoul has in place now. It is probable that the extent and the growth rates of negative externalities the megacity has had to deal with were far too high for it simply to sit back and wait for agreements on every aspect of policy action that was required.

An overview of Seoul’s urban policies would reveal that a full array of policy approaches, ranging from the command-and-control type of regulatory measures and market incentives/disincentives, to direct government investment and moral persuasion (Baumol and Oates 1988). It has taken the “accommodationist” approach (Banister 2003) of supplying the basic infrastructures in response to expanding demand, while implementing demand management strategies to keep demand in check, if necessary.

On the top of these classic policy typologies, it has also proactively made wise use of a highly innovative land delivery method in order to provide public infrastructures such as roads and parks—a land readjustment method used only in a few countries in the world—as well as embracing other less conventional models of infrastructure investment and provision, such as Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) and public corporations, as an effective provider of public services. It is worth noting that the significant role played by arm’s length, quasi-public corporations such as the Seoul Land and Housing Corporation (SH) is quite unique to Seoul, and to Korea for that matter.

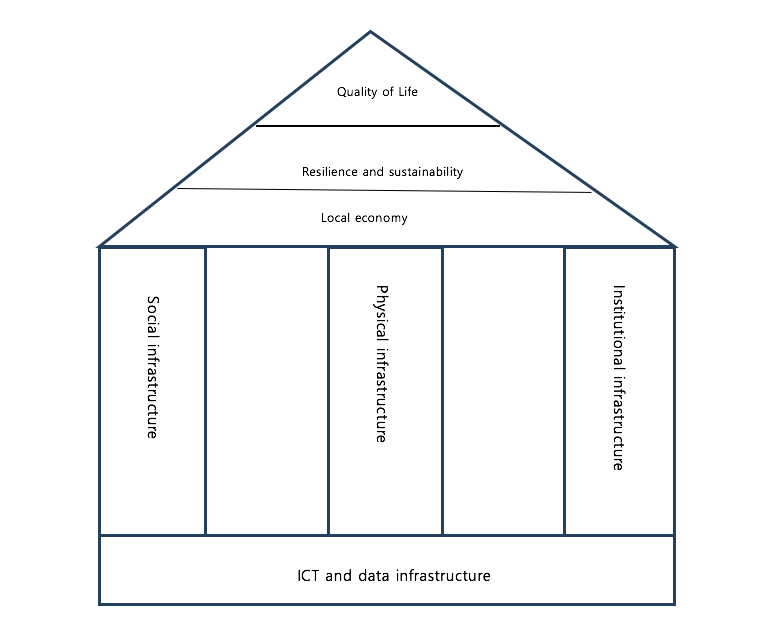

Figure 23 is an attempt to depict how the city has striven to achieve the values subscribed by citizens and contemporary global urban communities alike, including local economic well-being, sustainability, resilience and the quality of life. Illustrative policy responses and some of the key performance indicators seem to suggest that a large share of the urban investment was made in the area of infrastructure building.

Whereas the infrastructures associated with the current discussion tended to be focused on physical and virtual infrastructures, due largely to limited space and scope, the city underwent another set of compressed processes in developing and advancing its social and institutional infrastructures. A wider and closer view might better illustrate how important it has been in Seoul’s rapid progress through development in recent years to build smart infrastructures in all four areas, i.e. physical, social, institutional, and informational.

Figure 23. Seoul’s approach to Smart and Sustainable Megacity

References

- Asprone, D. and Manfredi, G. (2015) “Linking disaster resilience and urban sustainability: a glocal approach for future cities,” Disasters 39(1), pp. 96–s111.

- Banister, D. (2003) Transport Planning: In the UK, USA and Europe. Routledge, New York, NY.

- Baumol, W. J. and Oates, W. E. (1988) The Theory of Environmental Policy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Choi, S. (2014) Seoul’s e-government towards a smart city, proceedings for Global Lab on Metropolitan Strategic Planning, Seoul Global Exchange, April 28 – May 1, 2014.

- Davis, Diane (2104) "Sustainable Infrastructure: the role of politics and governance", Public Lecture Series “Urban Infra Forum”, International School of Urban Sciences, The University of Seoul, July 10, 2014.

- Friedman, J (1986) “The World City Hypothesis,” Development and Change 17(1), pp. 69-83.

- Godschalk, D. (2003) “Urban hazard mitigation: creating resilient cities,” Natural Hazards Review 4(3), pp. 136-143.

- Gunderson, L.H., Holling, C.S., Light, S.S. (1995) Barriers broken and bridges built: a synthesis. In: Gunderson, L.H. (Ed.), Barriers and Bridges to the Renewal of Ecosystems and Institutions. Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 489–532.

- Holling, C.S. (1973) “Resilience and stability of ecological systems,” Annual Review of Ecological Systems 4, pp. 1-23

- Howard, E. (1902) Garden Cities of To-Morrow. Faber and Faber, London.

- Jacobs, J (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House, New York NY.

- Knox, P. L. and Taylor, P. J. (Eds.) (1995) World Cities in a World-system. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Lo, F. and Yeung, Y. (1996) Emerging World Cities in Pacific Asia

- Mileti, D. (ed.) (1999) Disasters by design: A reassessment of natural hazards in the United States, Joseph Henry Press, Washington, D.C.

- Pickett, S.T.A, Cadenasso, M.L. and Grove, J.M.(2004) “Resilient cities: meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms,” Landscape and Urban Planning 69(4), pp. 369-384.

- Sassen, S. (1991) The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Satterthwaite, D. (1997) Sustainable cities or cities that contribute to sustainable development? Urban Studies 24(10), pp. 1667-1691.

- Seoul Institute, Evolution of Seoul – an overview with indicators, https://www.si.re.kr/indicator accessed 13 February, 2015 (in Korean).

- Seoul Institute, Evolution of Seoul – an overview with indicators: Key statistics and trends (2010 Revision), The Seoul Institute, https://www.si.re.kr/indicator accessed 28 January 2014. (in Korean).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government (2000) Seoul Statistics Yearbook 2000, SMG, Seoul, S. Korea.

- Seoul Metropolitan Government, Seoul Solution – Seoul’s Urban Policy Archive, https://seoulsolution.kr/ accessed 2 February, 2015.

- Song, J. (2014) Smart Waste Management in Seoul: From Waste to Resource, proceedings for Global Lab on Metropolitan Strategic Planning, Seoul Global Exchange, April 28 – May 1, 2014.

- Sorensen, A. and Okata, J. (Eds.) (2011) Megacities – Urban Form, Governance, and Sustainability. sSUR-UT Series: Library for Sustainable Urban Regeneration 10, Springer, Tokyo, Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York.

- South Coast Air Quality Management District (2007) Air Quality Management Plan, SCAQMD, Los Angeles, CA.

- The World Bank (2007) Development and the Next Generation, World Development Report 2007. The World Bank, Washington DC.

- The World Bank (2009) Reshaping Economic Geography, World Development Report 2009. The World Bank, Washington DC.

- The World Bank (2010) Development and Climate Change, World Development Report 2010. The World Bank, Washington DC.

- The World Bank (2015) The WB Country Profile http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/korea/overview, accessed 2 February, 2015.

- UNHABITAT (2014) A new strategy of sustainable neighbourhood planning: Five Principles, UN Habitat For A Better Urban Future Discussion Note 3 Urban Planning. Accessed 11 February, 2015 at http://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/5-Principles_web.pdf.

- Yoo, J (2014) Trade policy and economic development: The Korean experience, Public Lecture Series “Urban Infra Forum”, International School of Urban Sciences, The University of Seoul, December 11, 2014.