Development of Gangnam

Background

Need for New, Large Built-up Areas due to the Rapid Expansion of Seoul

Seoul’s population has grown at a phenomenal rate. It was a million in 1953, and skyrocketed to 2.45 million by 1960, up 1.5 million in less than a decade. There was no planning for such explosive growth, and urbanization quickly deteriorated quality of life and generated slum areas across the city. Disorganized urban sprawl characterized the city as it encroached on the mountains, rivers, green belts, national land, and even roads.

The shortage of adequate housing and deterioration of existing housing were serious issues: there was 1 housing unit per 2 households and at least a third of all dwellings were shoddy clapboard houses. Officially, the water service rate was 56%, but it was supplied only once an hour. The road ratio was only 8%, and it took 2 hours to commute across the city, which was only 16 km east to west and 268 ㎢ in area. Sewage was released into the river system without treatment, causing sanitation problems. There were not enough schools; tents were set up as temporary classrooms. Classes ran morning and afternoon, but there were not enough to accommodate everyone. Most citizens roamed the streets, unable to find work. Crime was rampant.

To accommodate the growing population, the city government planned to increase the density of the existing built-up areas (e.g., Seun Arcade) and systematically develop the adjacent areas (e.g., land readjustment programs in Seogyo, Dongdaemun, Myeonmok, Suyu, etc.). However, this was not sufficient to handle the dramatic population growth. For instance, population grew by 298,780 on average in 1960; this meant that the city needed at least 50,000 housing units (assuming 6 people in each household) and other infrastructure, which at the time could only service a few thousand. Seoul was in need of new, large built-up areas to resolve the snowballing urban issues.

“Gangbuk could no longer handle it. The population kept growing. The development of Gangnam first began in earnest in the 1970s, and the population was about 6 million at the time. Gangbuk couldn’t handle it. That’s how the development of Gangnam began.” (Son Jeong-mok, Former Director, Urban Planning Bureau, Seoul Metropolitan Government)

Expansion of Administrative Districts & Plans for Large Built-up Areas

In the early 1960s, population growth and urban problems became even more serious. As the population density reached an average of 100 persons/ha, the city doubled its administrative districts (Figure 1). With this decision, non-urban areas in the surrounding regions were absorbed by the city, thus setting off plans to develop new, large built-up areas. In 1965 various plans were developed such as the Seoul 10-Year Plan, the Arterial Road Network Plan, and the Greater Seoul Urban Plan. After much deliberation, the Basic Seoul Urban Plan was announced in 1966 (Figures 2 & 3). Development of Gangnam began as part of Seoul’s population dispersal policy, with an aim to have 40% of the population north of the Han River and 60% to the south (January 23, 1970, The Chosun Ilbo).

<Figure 1> 1963: Expansion of Administrative Districts in Seoul

.jpg)

In the early stage of the plan, Gangnam was to be one of many sub-centers. At the time, these sub-centers were supposed to be the hinterland and residential areas structurally and were thus located at the center of transportation hubs to enable easy access from the center of Seoul or other cities. On the contrary, Gangnam did not have any residential districts or built-up areas. Its planned density was not as high as we see today.

<Figure 2> Regions of Greater Seoul (Korea Planners Association Draft)

.jpg)

<Figure 3> Arrangement of Sub-centers

.jpg)

In the mid-1970s, development of Gangnam began in earnest. The “3 nuclei plan” added 3 nuclei to Seoul’s urban structure. Detailed plans were developed to turn Gangnam into a high-density urban center, just as we see today. It became one of the 3 major city centers of Seoul, alongside the old city center and Yeouido. Seoul designated Yeouido and the Yeongdeongpo area, where development began in 1970, as the commercial center while appointing Gangnam and Jamsil’s land readjustment districts as another city center and financial hub.

The third Hangang Bridge (today’s Hannam Bridge; begun January 1966 and completed December 1969) heralded the start of the era of Gangnam. When the Gyeongbu Expressway (begun in 1967) opened in July 1970, connecting the old city center to Gangnam, the development of Gangnam progressed even faster.

<Figure 4> 1960: Aerial View of Gangnam

.jpg)

Source: Korean National Archives

<Figure 5> 1969: Shinsa-dong, Gangnam-gu and the Third Hangang Bridge

.jpg)

Source: City History Compilation Committee of Seoul

Development Plans for Gangnam

The development of Gangnam proposed in the Basic Seoul Urban Plan was carried out as the land readjustment plan became more specific. Land readjustment became more detailed with the start of the Gyeongbu Expressway construction in 1967. A New Built-up Area Plan for Yeongdong District was announced, which would focus on developing Gangnam as a built up area, and creating residences for 600,000 people in District 1 and 2 (59 km²) of Yeongdong. The City of Seoul asked the Ministry of Construction to designate the Yeongdong Districts for land readjustment in September 1966; a decision was made to install the facilities as part of the readjustment plan in December of the same year. The enforcement decree for Yeongdong District 1 – the first project in the development of Gangnam – was the Ministry of Construction Notice #154, issued on December 15, 1967. The process from request to approval was accelerated, taking no longer than 2 years.

Readjustment of the land enhanced its use. Order was introduced to the disorderly arrangements of lots and parcels. Land for public use was secured; schools and other public structures were better located, and accessibility and traffic flow improved. Gangnam was developed as part of the land readjustment program for Yeongdong Districts 1 and 2. Gangnam was developed even more so after the addition of programs and program sites. Furthermore, the use of the land readjustment approach allowed land development costs to be paid by the party that would profit from the program.

Defined Urban Structure, Space Secured for Public Use, Creation of Infrastructure

The land readjustment programs in Yeongdong District 1 and Yeongdong 2 were launched in 1968 and 1971 respectively and were both completed in 1985. The land readjustment program in Yeongdong District 1 and 2 was clearly set apart from other land readjustment programs in Seoul by their objective. In 1963, Maljukgeori and its vicinity were designated as a sub-center as part of Seoul’s urban improvement plan and were again selected as the top 4 sub-center areas by the Basic Seoul Urban Plan in 1965. Accordingly, the development of Gangnam was launched to provide for a new town designed to disperse urban functions and population to undeveloped areas.

Land Use & Lots Secured for Public Use (Appendix 1)

The ratio of housing sites to total land in Gangnam was set lower than the national average while the ratio of the land for public use (such as roads and green belts) was set higher. While Gangnam was designed as a residential area, it had a higher ratio of land for public use compared to Gangbuk as the latter already had a built-up area.

In Yeongdong District 1, the land reduction rate was 39.1%. Public land is usually secured through program execution, and roads (road ratio: 23.1%) account for the largest percentage. It was markedly different from the previous land readjustment programs in that the overall ratio of public land – schools (5.5%), parks (1.74%), and other public land (10.52%) – was higher. As the land reduction rate increased, so did public land, but this also included utility infrastructure, leaving little room for green spaces. With the replotting plans for Yeongdong District 1, the land reduction rate continued to rise, but this too was rather passive, placing a priority on minimizing the land reduction rate, from today’s point of view.

<Table 1> Public Land Secured in Yeongdong District 1 & 2

|

Area |

Before the Program |

After the Program |

Land Reduction Rate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yeongdong District 1 |

Private Land |

94% |

Housing Sites |

53% |

|

|

General Land Set Out for Recompense* |

5% |

39.1% |

|||

|

National/ |

6% |

||||

|

Public Land |

42% |

|

|||

|

Yeongdong District 2 |

Private Land |

83% |

Housing Site |

58% |

|

|

General Land Set Out for Recompense * |

15% |

35.1% |

|||

|

National/ |

17% |

||||

|

Public Land |

27% |

|

|||

* This land is sold to the private sector and becomes private land but some percentage can be reclaimed for public land

Yeongdong District 2 was similar to Yeongdong District 1 in regard to land reduction rate and land use. Land reduction rate was slightly lower at 35.1% because District 2 had more national/public land but the percentage of parks and green areas was higher (4.8%). District 2 was much higher in terms of general land set out for recompense (15%), largely due to part of the Gyeongbu Expressway being located in District 1.

Lots & Housing

To prevent the issues of small land subdivisions that had occurred in existing land readjustment districts, subdivision was prohibited on land 165m² or smaller in area while construction was limited to 66m² (building-to-land ratio up to 40%) in 1972. Restricting the building-to-land ratio to 40% particularly contributed to creating a pleasant physical environment in Gangnam.

In 1973, the City of Seoul introduced the Yeongdong/Jamsil New Built-up Area Plan and the Yeongdong Development Promotion Plan; while restricting building size, color, and arrangement, the city sought to make plans and control the elements that replotting could not. In 1975, a decision was made to group the land secured for recompense, which had previously been located in the areas that were easy to sell; that same year, an apartment district was included in the district designated for specific use according to urban planning.

Designating and grouping the land secured for recompense for up to 50% of the area was done to sell the land to public corporations such as the Housing Corporation or to national housing builders. Since those public corporations eligible to purchase such grouped land were capable of high-density development, this measure of grouping the land for recompense and including the apartment district in the district designated for specific use provided the groundwork for and promoted high-density development in Gangnam.

“ ...Even if Seoul were covered with detached houses, there was not enough land for 10 million people. Apartments were the only solution. With apartments, we’d have high-density housing and still have some land. The urban environment would be improved, and the energy supply would be more efficient. You use less energy because you don’t have to move as much. According to plans to utilize national land, we needed apartments to have some land for landscaping. ….so we designated apartment districts. This wasn’t in the law yet.” (Kim Byeong-lin, former Director, Urban Planning Bureau, City History Compilation Committee of Seoul, 2012)

Infrastructure for Public Services

As land readjustment was being planned, plans for a road network and underground utility tunnels were also being developed for Yeongdong Districts, and made up the key infrastructure for Seoul, significantly helping Gangnam to perform its intended functions. The plans for Yeongdong Districts included: arterial roads that were 50 m or wider; arterial road networks inside the Districts, such as Samneung-ro (50 m, today’s Tehran Avenue), Yeongdong Avenue (70 m), and Gangnam Avenue (50 m); and the riverside roads that constitute today’s Olympic Expressway. The road ratio was 24.6% and arranged in a grid network, same as the road networks of major cities in advanced nations. There was strong criticism of such a high road ratio, but the road width was pursuant to the road networks from the Basic Urban Plan, and this plan was deemed reasonable when the automobile use soared in the late 1980s.

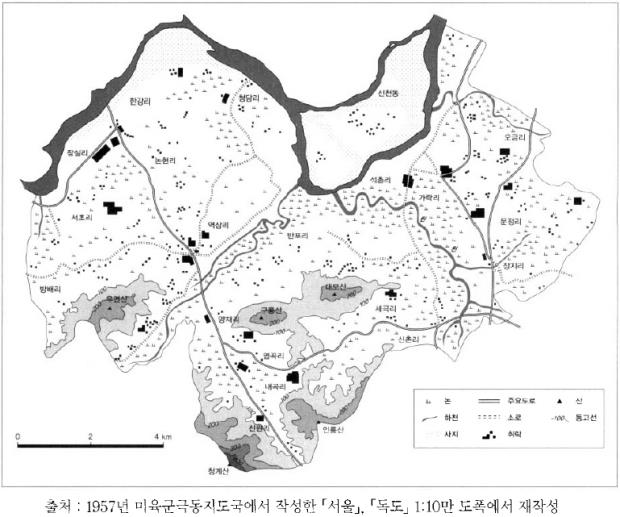

<Figure 6> Land Use before the Development of Gangnam (1957)

<Figure 7> Land Use during the Construction of Foundation in Gangnam (1974)

Source: Lee Ok-hee (2006), Characteristics & Problems of the Gangnam Development Process in Seoul, Journal of the Korean Urban Geographical Society.

Seoul also changed its city Metro plan. Established in 1972, the Metro plan was significantly revised in 1975; Line 2 was to become a circle line connecting Yeongdong Districts to Yeongdeungpo and Seoul’s city center. This would not only disperse the population of Gangbuk to Gangnam but also helped promote the 3-nuclei plan that would emerge a year later, giving a multi-nucleic structure to today’s Seoul (Son Jeong-mok 2003).

<Figure 8> 1972 City Metro Plan & 1975 Changes

.jpg)

Source: Capturing 600 Years of Seoul, Seoul Museum of History.

Underground utility tunnels were needed to connect the communications, electricity and waterworks lines to Gangnam, known as a flood-prone area. To develop Gangnam, waterworks, sewer lines, roads, communications, and gas lines were installed underground. Above ground, green spaces would create a natural landscape.

Financing for Land Readjustment in Yeongdong Districts

Because the City of Seoul could not finance the development of a new, large built-up area, it had to rely solely on the sale of land set out for recompense from the land readjustment programs. The program cost from Yeongdong District 1 and 2 can be seen in Table 2. In Yeongdong District 1, the sale of the land set out for recompense played a decisive role in financing the program. In addition to the 9.5% from the national coffers, revenue from land sales accounted for more than 90% - markedly different from the previous land readjustment programs. This difference was even more pronounced in Yeongdong District 2, where 99.9% of its program costs were paid with revenue from land sales.

<Table 2> Yeongdong District 1 & 2 Program Costs

|

|

Revenue (Unit: KRW 1,000) |

Expenses (Unit: KRW 1,000) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yeongdong District 1 |

Total |

4,725,800 |

Total |

4,725,800 |

|

Municipal Bonds |

- |

Office Expenses |

210,000 |

|

|

National Assistance |

- |

Construction Expenses |

10,510,000 |

|

|

Sale of Land Set Out for Recompense |

4,274,000 |

Maintenance |

4,000 |

|

|

Contribution |

0.1 |

Municipal Bond Interest |

- |

|

|

Liquidation Receivables |

5,000 |

Liquidation Cashout |

5,000 |

|

|

Misc. Income |

0.1 |

Reserve |

20,000 |

|

|

YeongdongDistrict 2 Land Readjustment |

Total |

10,683,000 |

Total |

10,683,000 |

|

Municipal Bonds |

- |

Office Expenses |

150,000 |

|

|

National Assistance |

- |

Construction Expenses |

10,510,000 |

|

|

Sale of Land Set Out for Recompense |

10,677,990 |

Maintenance |

4,000 |

|

|

Contribution |

0.1 |

Municipal Bond Interest |

- |

|

|

Liquidation Receivables |

5,000 |

Liquidation Cashout |

5,000 |

|

|

Misc. Income |

10 |

Reserve |

14,000 |

|

Difficulties with Gangnam Development & Policy Response

Development of Gangnam began in the early 1970s, but the population was still concentrated in Gangbuk. In 1970, the population of Seoul reached 5.43 million. The population had been 4.78 million in 1969 and had risen 630,000 in only one year. The population growth was even more drastic than in the 1960s and they were all headed to Gangbuk, where, by 1970, 76% of Seoul’s population lived. The overpopulation issue deteriorated by the day. The rest of the city’s population – 24% - lived to the south of the Han River, mostly in Yeongdeungpo. Yeongdong was therefore empty, and Seoul desperately needed to disperse its population.

Recommendations for Migration & Development Promotion Policies

In Gangnam where land development had just started, public servant apartments and city apartments were built. In 1971, public servant apartments were completed in Nonhyeon-dong. In the following year, the city apartments were built. With these, Seoul intended to encourage public servants and other citizens to move to less crowded areas within the city. The public servant apartments were sold to those at Seoul City Hall who did not own a home as well as to those at the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education and Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency, but it did not work as the city intended. In the end, Seoul had to exert significant pressure to get public servants to move into these buildings.

<Figure 9> Public Servant Apartment Complted in 1971 in Nonhyeon-dong

.jpg)

<Figure 10> City Apartments Completed in 1974 in Cheongdam-dong

.jpg)

Source: Korean National Archives

The program was still in its early days, and there were no adequate facilities or public transport to support those living in the area. Infrastructure was so poor that some of the migrants sold their houses in Yeongdong Districts and returned to Gangbuk. Despite many attempts to encourage public servants to move to these dedicated apartments, many returned to Gangbuk. People did not yet believe the development of Gangnam would succeed.

To make matters worse, external economic conditions were deteriorating. Global markets were sluggish, holding the South Korean economy back as well. Consumers were hesitant to spend and so were property buyers, creating problems for plans to sell the land set out for recompense to finance the development. Ultimately, this plan could no longer be pursued.

To promote the development of Gangnam, the government introduced the Act on Temporary Measures for Development Promotion in Specific Areas in 1972, easing the tax regulations that had been put in place to prevent real estate speculation and removing almost all taxes on land transactions and use. The real estate speculation tax, business tax, registration tax, acquisition tax, property tax, urban planning tax, and licensing tax were removed until the Act was abolished in 1978. This temporary measure proved effective: land transactions became more active, and prices rose again.

However, this Act once again attracted speculators who were not interested in the normal process of urban development, causing serious delays or even cancellation. Then the first oil crisis in 1973 froze the economy, stunting urban development again.

The Yeongdong/Jamsil New Built-up Area Plan of 1973 was drafted to promote the development of Gangnam by enabling an approach where the target area was divided into many zones with a central location that received intensive focus. In 1974, the government introduced a tax on vacant lots to curtail property speculation and promote urban development. The tax, which was quite heavy, was imposed on owners of vacant lots where there were no development activity 2 years after replotting.

The development of Gangnam picked up speed only after the sale of land set out for recompense was vitalized in 1975. Now that a source of program financing was in place again, Yeongdong Districts began to reveal their overall structure, defined by the roads. Development accelerated in Gangnam. By 1975, the population of Seoul was nearing 7 million. The central and Seoul governments strongly encouraged development and construction of major facilities in Gangnam through very attractive assistance programs and policies to discourage concentration in Gangbuk.

Discouraging Concentration in Gangbuk & Promoting Construction of Major Facilities in Gangnam

By expanding the concept of a special facility-restricted area to boost the growth of sub-centers in 1972, the government prohibited the development of housing sites north of the Han River. Apartment buildings and private housing could not be built or sites developed in Gangbuk. Construction or expansion of department stores, markets, universities, and other facilities that attract people to an area were forbidden. New restaurants, bars, university preparation schools, gas stations, and other facilities were either disallowed or obtaining a permit made very difficult. Seoul was determined to stop the overpopulation in Gangbuk.

In 1975, Seoul announced its plans to build the social infrastructure to develop urban functions in Gangnam. Its first targets were secondary government offices, such as the City Hall, court, Public Prosecutor’s Office, Korea Forest Service, and Public Procurement Service, as well as headquarters of 8 financial institutions, including the Bank of Korea, Korea Development Bank, and Korea Exchange Bank. However, this resulted in fierce opposition as the city did not hold sufficient discussions with the relevant departments, and the institutions were not moved to Gangnam. The only public offices that moved to Gangnam were the Supreme Court and the Public Prosecutor’s Office, but only after a decade.

<Figure 11> Supreme Court in Seosomun-dong (Gangbuk) in 1971

.jpg)

<Figure 12> Supreme Court in Seocho-dong (Gangnam) Today

.jpg)

Source: 40 Years of Gangnam, Seoul Museum of History

In 1976, the next targets were the prestigious high schools in the old city center. Starting with Gyeonggi High School, 8 high schools, including Hwimun High School and Sukmyung Girls’ High School, were moved to today’s Gangnam-gu. In 1980, Seoul High School moved to Seocho-gu, and Baeje High to Gangdong-gu. A total of 15 high schools were moved, creating the famous 8 school districts, and South Korea’s vehement pursuit of good education has fueled the continued migration to Gangnam ever since.

<Figure 13> Move of High Schools from Gangbuk to Gangnam

.jpg)

Source: 40 Years of Gangnam, Seoul Museum of History

The construction of bridges and the express bus terminal moving to Gangnam significantly vitalized the area. Besides the third Hangang Bridge (completed in 1969, today’s Hannam Bridge), Seoul built Jamsil Bridge, Yeongdong Bridge, Jamsu Bridge, Jamsil Rail Bridge, Seongsu Bridge, Banpo Bridge, and Dongho Bridge in 1972. While these structures enhanced the connection to and from Gangnam and the city center, they were more than just bridges; they also provided a link between the city center and satellite cities, expanding the extent of the city. Built in 1976, Gangnam Express Bus Terminal was completed alongside Jamsu Bridge, further promoting the development of Yeongdong District 1 and the move of urban functions to Gangnam.

Improved Development of Gangnam

.jpg)

Source: The Seoul Institute, Study of the Urban Structure of Seoul, 2009.

By the 1980s, no sizeable housing sites were available in Gangnam, and the land readjustment programs were drawing to a close. Nevertheless, housing demand remained high. Pursuant to the Housing Construction Promotion Act, a housing site development program was launched in Gaepo District. This plan involved developing large apartment complexes spanning an area of 8,534,900㎡ in today’s Gaepo-dong, Irwon-dong, and Dogok-dong in Gangnam-gu; Umyeon-dong in Seocho-gu; and Juam-dong in Gwacheon, Gyeonggi-do Province. In Gaepo District, the public corporations utilized the housing sites pursuant to the Housing Site Development Promotion Act, unlike with other apartment complexes, and applied the urban design concept to the area. Because of this approach, the area had much higher percentages of roads, public squares, parks, green spaces, schools, and other public infrastructure over other existing apartment areas. The expanded Gangnam area now had a better residential environment.

<Figure 14> Urban Design in Gaepo District

.jpg)

Source: 40 Years of Gangnam, Seoul Museum of History

The construction of large apartment complexes helped the area’s population to grow. In 1975 when Gangnam-gu was added as a new administrative district, its population was 320,000; by 1987, it had grown to 820,000 – higher than the population in the Gangbuk city center. Gangnam continued to grow, reaching nearly a million people (950,000) in 1995 when the commercial districts near Tehran Avenue had been completed (40 Years of Gangnam, 2011).

|

Area

|

Date Approved,

Date Completed |

Area

(㎡) |

Land Use (㎡, %)

|

Program Cost/

Area (KRW) |

Land Reduction Rate

(%) |

|||||||

|

Sale of Land Set Out for Recompense

|

Housing Site

|

Land for

General Public Facilities |

Total Public Land

|

|||||||||

|

Markets

|

Schools

|

Roads

|

Parks

|

Others

|

||||||||

|

Yeongdong 1

|

1968.1

1990.12 |

12,737,831

|

701,830

|

6,715,053

|

112,985

|

700,532

|

2,945,372

|

221,980

|

1,340,079

|

5,320,948

|

|

39.1

|

|

5.5

|

52.7

|

0.9

|

5.5

|

23.1

|

1.4

|

10.5

|

41.8

|

371

|

||||

|

Yeongdong 1

|

1971.8

1991 |

13,071,858

|

1,985,061

|

7,531,772

|

31.074

|

95,868

|

3,050,235

|

114,149

|

263,699

|

3,555,025

|

|

36.8

|

|

15.2

|

57.6

|

0.2

|

0.7

|

23.3

|

0.9

|

2.0

|

27.2

|

817

|

||||

|

Jamsil

|

1974.12

1986.12 |

11,223,191

|

1,805,175

|

4,812,932

|

|

440,826

|

1,662,681

|

170,456

|

2,331,121

|

4,605,084

|

|

52.9

|

|

16.1

|

42.9

|

|

3.9

|

14.8

|

1.5

|

20.8

|

41.0

|

900

|

||||

|

Yeongdong 1

Additional |

1971.12

1984.9 |

991,736

|

71,976

|

603,989

|

3,306

|

62,810

|

223,587

|

5,950

|

20,118

|

315,771

|

|

39.8

|

|

7.3

|

60.9

|

0.3

|

6.3

|

22.5

|

0.6

|

2.0

|

31.8

|

991

|

||||

|

Yeongdong 2

Additional |

1974.3

1982.9 |

85,369

|

17,977

|

48,716

|

|

|

17,684

|

992

|

|

18,646

|

|

39.5

|

|

21.1

|

57.1

|

|

|

20.7

|

1.2

|

|

21.9

|

1,084

|

||||

|

Gaepo 3

|

1982.2

1988.12 |

6,491,289

|

621,240

|

1,837,765

|

550,552

|

428,790

|

1,185,276

|

767,656

|

1,100,010

|

4,032,284

|

|

57.4

|

|

9.6

|

28.3

|

8.5

|

6.6

|

18.3

|

11.8

|

16.9

|

62.1

|

19,754

|

||||

|

Garak

|

1982.3

1988.12 |

7,455,066

|

1,589,284

|

1,343,121

|

137,582

|

407,440

|

1,545,024

|

466,055

|

1,966,560

|

4,522,661

|

|

68.3

|

|

21.3

|

18.0

|

1.8

|

5.5

|

20.7

|

6.3

|

26.4

|

60.7

|

15,157

|

||||

|

Yangjae

|

1983.11

1986.12 |

154,664

|

29,844

|

76,441

|

3,239

|

|

28,433

|

13,871

|

2,836

|

48,379

|

|

43.1

|

|

19.3

|

49.4

|

2.1

|

|

18.4

|

9.0

|

1.8

|

31.3

|

33,281

|

||||

|

Isu

|

1972.2

1981.12 |

2,028,277

|

439,104

|

1,119,617

|

13,223

|

23,827

|

402,368

|

22,092

|

8,046

|

469,556

|

|

39.4

|

|

21.6

|

55.2

|

0.7

|

1.2

|

19.8

|

1.1

|

0.4

|

23.2

|

394

|

||||

|

Isu, Additional

|

1981.4

1985.6 |

76,608

|

18,212

|

25,702

|

|

|

29,299

|

3,395

|

|

32,694

|

|

53.3

|

|

23.8

|

33.6

|

|

|

38.2

|

4.4

|

|

42.7

|

23,917

|

||||

|

All of Gangnam

|

|

54,315,889

|

13.5

|

44.4

|

1.5

|

4.0

|

20.4

|

3.3

|

12.9

|

42.1

|

5,132

|

|

|

*National

|

|

140,019,379

|

10.4

|

51.5

|

0.9

|

2.4

|

20.1

|

1.7

|

7.6

|

34.6

|

2,448

|

|

|

Source: Urban Planning Bureau, Seoul Metropolitan Government.

Note: The total land readjustment area across the nation since 1960. (Source: Lee Ok-hee (2006), Characteristics & Problems of Gangnam Development Process in Seoul, Journal of the Korean Urban Geographical Society.) |

||||||||||||

Source: 40 Years of Gangnam

.jpg)

Appendix 3. History of the Development of Gangnam

|

Year

|

Description

|

Total Population

(Gangbuk; Gangnam) |

GDP ($ 1 billion)

GDP per capita ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1951

|

|

650,000

|

|

|

1956

|

|

1.5 million

|

|

|

1960

|

|

2.45 million

|

|

|

1962

|

|

|

2.7459

|

|

1963

|

-Gangnam absorbed by Seoul during expansion of the city’s administrative districts

|

|

3.8637

|

|

1965

|

- Seoul 10-Year Plan established

- Seoul Urban Plan established |

3.47 million

|

3.0176

|

|

1966

|

- Basic Seoul Urban Plan announced

- Development of Yeongdong decided - Construction of Hannam Bridge begun |

|

3.806

|

|

1967

|

|

|

4.7027

|

|

1968

|

- Yeongdong District 1 program launched

|

|

5.9553

|

|

1969

|

-Hannam Bridge opened for service (Gyeongbu Expressway opened)

|

|

7.4757

|

|

1970

|

|

(4,115,133 75.6%;

1,328,165 24.4%) |

8.8997

$299 |

|

1971

|

- Yeongdong District 2 program launched

|

|

9.8514

$325 |

|

1972

|

- Seoul Express Bus Terminal in Gangbuk, near Seoul Station

- Restricted area for specific facilities adopted - Act on Temporary Measures for Development Promotion in Specific Areas introduced -Plans developed to build additional apartments for public servants |

|

10.7356

$347 |

|

1973

|

|

|

13.6915

$435 |

|

1974

|

- Pilot housing complex established in Yeongdong.

|

|

19.2294

$599 |

|

1975

|

- Development of housing sites prohibited to the north of the Han River

-Plans to move City Hall, the court, Public Prosecutor’s Office, Korea Forest Service, Public Procurement Service, the Bank of Korea, Korea Development Bank, and Korea Exchange Bank (headquarters of 8 financial institutions) - Plans for city Metro Line 2 changed to make it a circle line |

|

21.4589

$657 |

|

1976

|

- Gyeonggi High School relocated

- Gangnam Express Bus Terminal (Phase 1) completed (Gangbuk bus terminal taken down) - ‘Apartment district’ concept introduced (Enforcement Decree of the Urban Planning Act) |

|

39.5548

$888 |

|

1977

|

- Samneung-ro changed to Tehran Avenue

|

|

37.9262

$1,123 |

|

1978

|

- The Act on Temporary Measures for Development Promotion in Specific Areas abolished

- Construction of Metro Line 2 (circle line) begins |

|

51.1252

$1,493 |

|

1980

|

- Metro Line 2 opens, from Shinseol-dong to Sports Complex

|

(4,981,687 56.6%;

3,382,692 40.4%) |

63.8344

$1,890 |

|

1981

|

|

|

71.4692

$1,810 |

|

1982

|

-2nd segment of Metro Line 2 opens, from Sports Complex to Seoul National University of Education

|

|

76.2182

$2,004 |

|

1983

|

-3rd segment of Metro Line 2 opens, from Seoul National University of Education to Seoul National University

|

|

84.5106

$2,111 |

|

1984

|

- Metro Line 2 completed

|

|

93.211

$2,303 |

|

1985

|

- Yeongdong District 1 and 2 programs completed

|

(5,214,760 54.1%;

4,424,350 45.9%) |

96.6197

$2,505 |

|

1986

|

|

(5,242,624 53.5%;

4,555,918 (46.5%) |

111.3056

$2,561 |

|

1987

|

|

(5,267,177 52.7%;

4,723,912 47.3%) |

140.0056

$2,917 |

|

1988

|

|

(5,381,815 52.3%;

4,904,688 47.7%) |

187.4465

$3,630 |

|

1989

|

-Phase 1 construction begins of new town development

1989 – 1996: Bundang; 1990 – 1995: Ilsan; 1989 – 1995: Pyeongchon and Sanbon; 1990 – 1996: Jungdong |

(5,476,956 51.8%;

5,099,838 48.2%) |

230.4731

$5,847 |

|

1990

|

- Comprehensive plan for balanced development of Gangnam and Gangbuk – regulations eased on Gangbuk

|

(5,481,243 51.6%;

5,131,334 48.4%) |

263.777

$6,626 |

|

1991

|

- People begin moving into Bundang

- Seoul’s population peaks |

(5,578,106 51.2%;

5,326,421 48.8%) |

308.185

$7,663 |

References

· Kim Jin-hee, 2011, “Significance of ‘Comprehensive Development Framework Plan for Jamsil District’ in Seoul’s Urban Planning in the 1960s – 1970s”, University of Seoul Doctoral Dissertation.

· Kim Eui-won, 1983, Introduction & Progress of the Land Readjustment Program in South Korea, 18(2), p.8-25.

· The Seoul Development Institute, 2001, “History of Space in 20th Century Seoul”.

· The Seoul Development Institute, 2001, “History of Living & Culture in 20th Century Seoul”.

· The Seoul Institute, 2013, “Seoul in Maps”.

· Seoul Museum of History, 2011, “40 Years of Gangnam: from Yeongdong to Gangnam”.

· Seoul Museum of History, 2013, “Capturing 600 Years of Seoul”.