城市规划与管理

Trends in Urban Planning & Development by Time Period

Before the fall of the Joseon dynasty, Seoul underwent gradual changes in space, focused mainly on the center of the walled city, Mapo, and Yeongdeungpo. After liberation from Japanese colonial rule and into the 1960s, the city experienced an explosive growth in population and urban development. In 1966, the Basic Urban Plan was set up to respond to these changes and to lead the change through a long-term vision with systematic and comprehensive planning. Today, Seoul’s urban development serves as a model to other partnering economies.

Period 1: Expansion of Basic Infrastructure (1960 – 1979)

Economic development plans in the 1960s attracted a phenomenal number of people to Seoul, with approximately 500,000 people moving to the city within one 2-year period. Such massive migration of jobseekers with no ties to the city contributed directly to the formation of poor, unauthorized settlements throughout the city. The outskirts, which had been non-residential, were inundated with the new arrivals and quickly became part of the burgeoning capital. The inclusion of Gangnam and the northeastern areas – an addition of 594 km2 – to the city in 1963 doubled its size. The sudden growth of population (3 million at the time) ultimately led to extreme traffic congestion, environmental pollution, an overburdened public transit system, overcrowded residential areas, and rampant development of unauthorized settlements.

Construction Projects as the Solution

To address traffic congestion, existing roads were expanded and new arterial roads, overpasses, and underground roads were built. It was around this time that the Cheonggye Stream was uncovered and restored to create Seoul’s first overpass – Cheonggye Overpass. Countless pedestrian overpasses and underpasses were also built to enhance traffic flow. By 1967 the Yeouido area, inundated every flood season, saw the addition of a new urban district of over 900,000 pyeong (approximately 2.97km2) of land. The Seoul City government began to focus on removing unauthorized settlements and redeveloping those areas. Inner city slums and red-light districts were demolished and department stores and large commercial/residential complexes (e.g., Seun Arcade) took their place. The poor neighborhoods on the hillsides became the site of apartment complexes. Through this flurry of activity, some 400 apartment buildings were erected in the city in 1969 alone.

Continued Land Readjustment to House the Population

The land readjustment program begun under Japanese colonial rule and continued into the mid-1980s across various regions, significantly influencing Seoul’s current inner city structure. Land was readjusted to systematically develop and revamp built-up areas while minimizing public costs in the establishment of infrastructure and laying of foundations for private development. In Seoul, the program was implemented with a goal to redistribute the concentrated inner-city population and industrial facilities out to surrounding areas. The program also centered on detached housing which was then universal, based on which lots were divided. During this time, readjustment took place in Seogyo, Dongdaemun, Suyu, Bulgwang, and Seongsan districts.

The First Institutional Measure for Urban Planning

This particular time period was marked by a need for new urban planning legislation in order to address the housing, transportation and infrastructure made inadequate due to poverty and population growth. The Joseon Town Planning Ordinance, enforced after liberation but only until the late 1950s, had been introduced by the Japanese Governor-General in Korea to promote the national interests of colonial Japan. In 1962, it was divided into the “Urban Planning Act” and the “Construction Act”, two independent legislations for the sovereign nation. This new Urban Planning Act was the first institutional measure for urban planning taken by the Republic of Korea. It included provisions for the improvement of poorer districts, and urban planning decisions were to be made through Central Urban Committee resolutions. The Land Readjustment Program Act was enacted in 1966, and the concept of replotting was introduced to renew basic infrastructure (roads and parks, etc.) at minimum public cost. The Act set forth regulations on implementation, methodology and cost so as to promote the land readjustment program, thereby encouraging healthy development of the city and its public works infrastructure.

|

Seoul’s Urban Planning in the 1960s |

|---|

|

○ 1966: The Basic Urban Plan - The Basic Urban Plan of 1966 was a turning point in shaping the spatial structure of Seoul. The target was to increase the population to 5 million by 1985, and consisted of a central area and 5 sub-central areas, with the central area being the city center and Yongsan, and the sub-central areas being Changdong, Cheonho, Gangnam, Yeongdeungpo, and Eunpyeong. The central area was planned as the heart of political administration, with the legislature in South Seoul (currently Yeongdong) and the judicature in Yeongdeungpo. The residential structures in both the central and sub-central areas were encouraged to be high-rise, and a concentrated network of streets was to radiate out and connect the central and sub-central areas to each other. |

The 1970s: Establishment of Housing & an Urban Infrastructure

In the 1970s, Korea enjoyed astonishing economic growth. The per-capita income was approximately 250 USD in 1970, but exceeded 1,000 USD by 1977. Primary in importance to this accomplishment was Seoul, as the city had many export-oriented light industries, including sewing factories at the city center and other industrial regions on the outskirts. This continued the inflow of people seeking jobs and opportunities for a better life while the city continued to grow quickly, reaching 6 million residents by 1975.

The Expansion of Seoul and Miracle on the Han River

Around this time, tension between North and South Korea increased and Seoul needed a new strategy for itself. As a way to develop Gangnam and expand the city in general, the concept of development-prohibited areas was adopted. The decision to develop Gangnam was in order to redistribute urban functions away from the Gangbuk area. Additionally, the Gyeongbu Expressway was built to transport workers and resources. Accordingly, the land readjustment program was introduced to the agricultural Gangnam area. A grid of arterial roads was built, and the area was soon occupied by legal offices, detached houses for the social upper class, large-scale apartments and shopping centers, high-rise office buildings, and historical secondary educational institutions migrating from Gangbuk. Development of Yeouido, which started in the 1960s, was pushed forward in earnest, with the area becoming home to the National Assembly as well as high-rise office buildings and residential neighborhoods.

In 1973, the administrative districts in Seoul were expanded to 605 km2, similar to their size today, but there were ongoing requests for expansion of infrastructure and urban construction in order for the city to keep pace with the rapid economic growth. To meet these demands, Seoul replaced its outdated trams with a new subway service in 1974 (Line 1 today). In the meantime, construction of commercial and cultural facilities (high-rise office buildings, high-end hotels, trading centers, art and cultural centers, etc.) and the larger infrastructure (arterial roads, tunnels, bridges, sewer systems etc.) continued. The volume of work accomplished and South Korea’s dramatic economic growth was referred to as the Miracle on the Han River by the international community.

The 1970s, an era marked by rapid industrialization and economic growth, continued to see further urbanization, which led to demands for a new administrative framework capable of dealing with urban planning and relevant legislation across various sectors. In particular, the Urban Planning Act underwent a full revision in 1971 and featured an enhanced district system, introducing the concept of development prohibited areas as a way to control chaotic urban expansion and promote healthy development of built-up areas. With this revision, renewal of poorer districts was given a new name – the Redevelopment Program – and detailed procedures were prescribed for implementation. In 1976, the Urban Redevelopment Act was enacted to establish an institutional framework to prevent deterioration of the city center and overhaul the areas of unauthorized housing built in and around the city. Other legislation included the Act on Utilization & Management of the National Territory (1973) towards management and planning efficiency, and the Housing Construction Promotion Act (1973) for fundamental resolution of housing issues.

|

Seoul’s Urban Planning in the 1970s |

|---|

|

○ 1970: Modification of the “Basic Urban Plan” - The population of Seoul surpassed 5 million by the early 1970s, and the need to modify the Basic Urban Plan was inevitable. The target year for completion of the modifications was 1991, while the target population was 7.6 million. The single-nucleus CBD (Central Business District) system was maintained while adding two additional sub-central areas for a total of seven: Miah, Mangwu, Cheonho, Yeongdong, Yeongdeungpo, Hwagok, and Eunpyeong. Yeongdong held the administrative functions while Yeouido became the seat for the legislature and the new business area. The street network was of a radial and circular type, comprised of 3 circular and 8 radiating lines. ○ 1972: The “Revised Comprehensive Plan” - While it did not constitute a part of the Basic Urban Plan, the Revised Comprehensive Plan served as a guideline for the city’s development administration. It also targeted the year 1991 and a population of 7.5 million. The urban structure was to be the same as that of 1970, but more street networks were added: the Plan constituted 3 circular and 14 radial roads. ○ 1978: The “Basic Seoul Urban Plan” - In need of an urban development plan that would address the changes of the 21st century, the Basic Urban Plan was updated, targeting the year 2001 and a population of 7 million. It was designed to contain overpopulation and disorderly urban sprawl, reconfigure urban functions and facilities, promote balanced urban development based on building multi-nuclei, and encourage people to live closer to their places of work. Development of Gangnam was also facilitated as one of the solutions to congestion and overpopulation in Gangbuk, to even the balance between Gangbuk and Gangnam, which are located on opposing sides of the Han River. The existing city center was considered one national center, supported by an urban structure comprising 7 local centers (Yeongdeungpo, Yeongdong, Suyu, Jamsil, Janganpyeong, Susaek, and Hwagok), 27 district centers, and 157 community centers. The Plan also aimed to preserve and maximize the east-west blue axis and the north-south mountain axis near the Han River and to create a large green belt connected to the nearby development prohibited areas. As for the transportation system, the arterial road system was rearranged to facilitate the subway system and passenger vehicle travel and supplement the radial artery road system. The street network grid was introduced to encourage the growth of multiple nuclei. |

Period 2: Urban Growth (1980 – 1999)

In 1980, Seoul had become a very large city with a population of 8.5 million: within 8 years, it would be 10 million. Through unprecedented rapid economic growth, Seoul witnessed the emergence of large corporations, diversified industrial structures, and a strong middle class. After the death of former President Park Jeong-hee, who had led the economic development in the 1960s and 1970s, the socioeconomic changes in the following decade called for sustainable urban growth that would match the development as well as in the past.

City Overhaul for the Olympics

As host for the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Olympics, Seoul felt it necessary to improve and beautify itself. In Jamsil, large stadiums, Olympic parks, residences for athletes and other facilities related to the Olympics were built. In the meantime, the Han River and the nearby areas were also targeted. Through this project, the riverside lands – now used as city waterfront parks – were developed, and sewer lines installed on either side of the river to prevent water pollution. City highways were paved alongside the river to connect Gimpo International Airport to the city center and the Olympic stadiums. Subway expansion also followed to resolve traffic congestion. These things were already in the existing plans, but were expanded for the upcoming Olympics. In 1984, Subway Line 2 was opened, followed by Line 3 and 4 in 1985.

City Center Redevelopment & Construction of Housing

Redevelopment projects for the city center – overhauling the inner city slums to supply more space for business – became active, boosted by the high development density and tax benefits of the 1980s. At the time, the City of Seoul approved over 70 redevelopment projects, which modernized the traditional city center. To improve functionality and beautify the capital, city design projects were carried out along Eulji-ro and Tehran-ro in Gangnam.

The government also paid attention to redevelopment of areas with poor or inadequate housing and the construction of new residential buildings. The extensive farmlands and forests in the Gangnam, Mokdong, Godeok, Gaepo, and Sanggye areas were replaced by large apartment complexes. Companies discovered that building apartments in a city with a longstanding housing shortage was highly profitable. An apartment boom was fueled, which changed the face of Seoul entirely.

By the 1980s, a series of significant issues arose due to the rapid economic growth resulting in overpopulation and a city crowded with industry. Demands increased for updated housing and amenities for greater housing stability as well as for improved urban design to match the enhanced standards for education, culture, medicine, and other facilities. In 1981, the government amended the Urban Planning Act. With the Basic Urban Plan in place, the 3-phase urban planning system (Phase 1: the Basic Urban Plan; Phase 2: Urban Plan Overhaul; Phase 3: Yearly Execution Plan) was implemented, and an urban design system was introduced to provide more detailed guidelines and information on managing land use. Another adopted institutional measure was public participation, giving opportunities to local residents at public hearings. A number of laws were put in place such as the Housing Site Development Promotion Act (1981) for the supply of extensive housing sites and the Act on Temporary Measures for the Improvement of Dwelling and Other Living Conditions for Low-Income Urban Residents (1984).

|

Seoul’s Urban Planning in the 1980s |

|---|

|

○ 1980: The “Mid- to Long-term Plan for Urban Development in Seoul” - The Basic Plan was revised in accordance with the higher-level Seoul Metropolitan Area Readjustment Planning Act, targeting the year 2001 and a population of 9.45 million and including plans for the mid- to long-term. During the mid-term development period (1980 – 1986), urban structure would be updated where necessary according to actual changes and basic direction of the Plan; in the long-term structural planning period (1987 – 2000), the focus would be on the use of highly dense land, development of a multi-nucleic structure, living sphere plans, and the urban environment. This Plan did not include detail on the urban spatial structure but categorized the “living spheres” into 18 large, 90 medium, and 333 small spheres. ○ 1984: The “Multi-Nucleic City Development Research for Urban Restructuring” - Revision of the Urban Planning Act in 1981 was to result in the Basic Urban Plan becoming law and adjustment of the higher level Seoul Metropolitan Area Readjustment Plan. In 1984, the Basic Urban Plan of Seoul was reworked to reset the direction for urban development. It proposed a new direction for Seoul for the 2000s and guidelines for urban restructuring and readjustment. The target year was 2001 and a population of 10 million, but the Basic Urban Plan failed to become law due to the delayed public hearings. Suburbanization, sprawl, and expansion were managed through the building of satellite cities and decentralizing development, which led to Seoul becoming a multi-nucleic city. The single-nucleus network of transportation was restructured by turning the circular/radial street network into a grid. The CBD (CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT) would be made up of one main nucleus in the primary center, with 3 minor nuclei (Yeongdong, Yeongdeungpo, and Jamsil), 13 secondary centers, and 50 district centers. |

After the Olympics Games, Seoul became a megacity with a population of 10 million with a per-capita income of over $10,000. As the capital of a modernized industrial nation, Seoul required enhanced and further diversified urban restructuring to meet the needs of the ever-growing economy and population.

Many public projects were carried out during this decade, including expansion of the subway system. Four subway lines (Lines 5, 6, 7, and 8) were added and new bridges, highways, and art and music centers were built as part of the central and Seoul government plans. High-rise buildings constructed by the private sector changed the skyline of the city especially in the Gangnam area. The increased ownership of private cars and the construction of highway networks contributed to urban expansion beyond the development prohibited areas. Five new towns, such as Bundang and Ilsan, were created, and development continued on the surrounding outskirts, all serving as local centers of a metropolitan area. However, Seoul had new issues – unemployment, labor unrest, increased homelessness and the need for greater social welfare – that the Asian financial crisis of 1997 had brought to the forefront.

Significance of Managing the Old City Center

As Seoul had served as the capital of the Joseon Dynasty for hundreds of years and as the nation’s capital, the city government became acutely aware of the significance of restoring Seoul’s ancient city walls and cultural heritage that was slowly being eaten away by urban growth and development. In 1990, the Namsan Mountain Restoration program was initiated to protect this mountain in the middle of the city. An association made up of experts, ordinary citizens and local residents was organized, and it soon realized that its key agenda would be the removal of foreigner apartments and moving of the Agency for National Security Planning and the Capital Defense Command that stood in the way of Namsan’s beautiful view. The Command was replaced with Namsan Hanok Village, a small restoration of the ancient hillside village from the Joseon Dynasty, and in 1994 the apartments were demolished, finally clearing the view. With this campaign, the public began to appreciate the importance of managing the old city center, rich with historical and cultural heritage.

By this time, local government administrations had been brought back to life. City administration and urban planning, which had so far been top-down, now appeared with a new face – public participation and new administrative procedures. The 25 local administrative districts in Seoul were given more leeway, each working on their own diversified plans, facilities, and activities.

As such, the 1990s saw the introduction of different systems and initiatives: the Wide-area Plan was devised to efficiently build and manage infrastructure (roads, railroads, waterworks etc.) that required a wider perspective for systematic maintenance, while the Detailed Planning Initiative was adopted to specify building use, the number of floors, and the floor space ratio of the buildings in certain areas so as to make better use of the land and beautify the city at the same time. In line with democratic and decentralized governance, most of the urban planning authority held by the Construction & Transportation Minister was transferred to the City Mayors or the Provincial Governors. Before approving the Basic Urban Plan, the Minister was required to listen to the views of local councils and incorporate them into the Plan.

|

Seoul’s Urban Planning in the 1990s |

|---|

|

○ 1990: The “Basic Seoul Urban Plan” for the 2000s - The Basic Urban Plan of 1990 was more significant as it was the first statutory plan for the City of Seoul. It set 2001 and a population of 12 million as its targets. It aimed to balance development in both the Gangnam and Gangbuk areas by providing standardized placement of essential facilities, road grids, and enhanced access and connection points to city areas where key activities were carried out. It was designed to continue activities in the existing city center while allowing for flexibility in the multi-nucleic structure and increasing the role of the secondary centers. The urban structure in the Plan comprised of one city center within the Four City Gates area, 5 secondary centers (Shinchon, Cheongnyangni, Yeongdeungpo, Yeongdong, and Jamsil), and 59 district centers. ○ 1991 – 1995: A Basic Urban Plan for the Autonomous Districts - In July 1991, the City of Seoul prepared a Basic Urban Plan for the autonomous districts and instructed each gu (district) office to develop its own basic plan from December. The top-down planning structure of the existing Basic Plan was amalgamated with the new bottom-up planning system to provide for more detailed and effective urban planning. In this process, the local characteristics of and input from the local communities were deemed particularly important. This Plan was a long-term comprehensive scheme at the autonomous district level, taking into consideration the different characteristics of each district in setting the direction of and strategies for future development. The projects included in the Plan had yearly execution plans. ○ 1997: The “Basic Seoul Urban Plan” for 2011 - It was understood that the Basic Urban Plan established in 1990 required a feasibility review and revision. In 1997, a new Plan was thus established, with the year 2011 and a population of 12 million as its targets. The Plan proposed a vision of a 21st century Seoul, distinguished priority tasks from sustainable tasks, and came up with long-term goals and policy directions to be carried out in the following 15 years. While the Basic Urban Plan of 1990 was Seoul-oriented, the 1997 Plan encompassed a wider approach to the distribution of urban functions and to the transportation network. The 1990 Plan was physical facility-intensive while the new Plan put more emphasis on |

Period 3: Sustainability (2000 – Present): A City of Class & Public Participation

Having hosted the 1988 Olympics and other international events with success, Seoul earned its place as one of the world’s great international cities. In the meantime, the influence of the city became even more widespread, with Seoul and the nearby regions creating a single living sphere. Meanwhile, as local governments became more autonomous, the City of Seoul enacted the Urban Planning Ordinance in July 2000 (the first in Korea), in which the matters commissioned to local autonomous governments were specifically regulated. The overall tone of the urban development policies also changed from growth to sustainable development.

Accomplishments with the Seoul City Center Management

1994 was the 600th anniversary of Seoul being designated the capital city. To efficiently manage this historical city, a number of plans were launched: the City Center Management Plan (1999); the City Center Development Plan (2004); the Comprehensive City Center Recreation Plan (2008); and the Historical City Center Management Plan (2010). Other projects were also put in place to return to the citizens the space that had been otherwise used for traffic-oriented development projects. Examples include the restoration of the royal palaces (e.g., Gyeongbok Palace, Changdeok Palace, Deoksu Palace) and Jongmyo; construction of Seoul Plaza, Sungnye Gate Plaza, and Gwanghwamun Square; and the addition of open spaces in the city center. Other efforts included the creation of an eco- and pedestrian-friendly environment within the city, such as the restoration of Cheonggye Stream, the transformation of Dongdaemun Stadium into a city park, and the launch of the Open Nam Mountain campaign. The city also sought to reclaim its identity as a timeless historic yet modern city by restoring its historical and cultural heritage such as the Bukchon Village Beautification program, restoration of ancient city walls, and inclusion of Hanyang township – the ancient capital of the Joseon Dynasty and today’s Seoul –on the UNESCO Cultural Heritage list.

Seoul’s Endeavor to Be an Advanced City

In 2002, the pilot “New Town” project was launched in the Eunpyeong/Gireum/Wangsimni region in an effort to narrow the wealth gap between Gangnam and Gangbuk and establish or improve the infrastructure. From then until 2007, a total of 26 regions were appointed to be a part of the New Town project.

Also in 2002, Korea and Japan co-hosted the World Cup. In preparation, the Nanjido landfill site in the Sangam area, west of Seoul, was entirely transformed; an environmentally-friendly eco-park, the World Cup Stadium, and Eco Village were built, and the Digital Media City (DMC) was developed using cutting-edge IT. This, however, was only the beginning. Seoul took on a variety of activities developed by each region, such as the Han River Renaissance and the Northeast Region Renaissance, with the latest development projects including the Yongsan International Business District and Magok District.

To be the advanced city it aspires to be, Seoul has poured its energy into urban design and endeavors to make the changes necessary to turn itself into a city of beauty and class. Examples of where this energy has become reality include regional parks (Dream Forest in North Seoul, Seoul Forest, Pureun Arboretum, etc.); the pathway on the ancient city walls; the Seoul walking trail from Oesasan Mountain to neighboring peaks; the pedestrian and bicycle path along the Han River and its branches; and walking trails such as the Eco & Cultural Trail that connects the parks, mountains and streams. Pedestrian areas – Gangdong Greenway and Design Street – were also modernized. Seoul also urged people to walk more and enjoy the city’s rich history, culture and tourist attractions. To this end, some of the streets have been designated for pedestrians only.

Seoul continues to enhance itself even today. It has successfully recovered its historical and cultural identity and developed itself into an international high-tech city. It has implemented urban policies designed to promote balanced development within its boundaries. During the 2000s, it became particularly important to encourage public participation in decision-making towards social consensus. In the Seoul Plan 2030, the Citizen Board, and in the following living sphere plan, residents’ boards were organized to take an active part in developing future plans.

Into the 2000s, the institutional framework related to urban planning was greatly affected by the social conditions of the time and changed accordingly. The Urban Planning Act (2000) was also considerably revised. The living sphere grew bigger by the day as the city continued to grow outwards, aided by improved transportation. The growth had to be managed, and the wider urban plan for Seoul was instituted to do just this for 2 or more administrative regions. Reckless development of the Seoul metropolitan area was to be prevented under the "Plan First, Develop Later" system. With concerns rising regarding land tied to long-term urban facility projects not yet begun, a "Request for Purchase" system was introduced to improve unrealistic regulations. Other regulations on restricted development areas, a concept from the 1970s, were later separately addressed and managed by the Act on Special Measures on the Designation & Management of Development Prohibited Areas (2000). This can be seen as a reflection of the circumstances of the time – stimulus for a construction industry that had underperformed due to the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, corrective action on regulations encroaching on property rights, and a desire to reverse overcrowding and environmental degradation. In other words, the paradigm where priority was on development and growth changed to a greater emphasis on the environment and sustainability, and legislation systematically reflected this changing view.

The Urban Planning Act, which applied to cities, and the Act on Utilization & Management of National Territory, which loosely managed non-urban areas, were integrated and revised to unify the land use management system. In 2002, the Urban Planning Act (1962) and the Act on Utilization & Management of National Territory (1973) were each revised into the Framework Act on National Land and the Act on Planning & Use of National Territory, respectively. The city design plans and the detailed planning initiatives, provided for similar purposes, were also integrated into the plans at the district level. The provisions on urban development projects in the Urban Planning Act were combined with the Land Readjustment Program Act to create the new Urban Development Act (2000), while the Urban Redevelopment Act (1976) and the Act on Temporary Measures for the Improvement of Dwellings & Other Living Conditions for Low-Income Urban Residents (1984) were merged into a new Act on Maintenance & Improvement of Urban Areas and Dwelling Conditions for Residents (2003). As such, in the 2000s, related or overlapping urban plans were brought together to simplify the system and add more details to the provisions. By 2010, the Seoul City government was increasingly conscious of the necessity to revitalize and update the city as it witnessed a decrease in population, changes in industrial structure, reckless and unregulated expansion, and dilapidated residential areas, leading to the enactment of the Special Act on Activation & Support of Urban Restoration (2013).

|

Seoul’s Urban Planning in the 2000s |

|---|

|

○ 2006: The “Basic Seoul Urban Plan” for 2020 - The Basic Seoul Urban Plan for 2020 was a revision of and supplement to the 1997 Plan, targeting the year 2020 and a population of 9.8 million. The existing plan’s CBD (Central Business District) system was maintained to ensure consistency in policy. If the Basic Urban Plan of 2011 is considered to comprehensively embrace the material and socioeconomic aspects, the Basic Urban Plan for 2020 was more strategic in nature, with clear priorities, goals and strategies. The 2020 Plan also reflected expert and public opinion, proposed goals and a monitoring index, and provided direction for urban development in each of the 5 living spheres as one of the ways to promote balanced regional development. Its urban spatial structure is comprised of one primary center, 5 secondary centers (Yeongdong, Yeongdeungpo, Yongsan, Cheongnyangni/Wangsimni, and Sangam/Susaek), 11 local centers, and 53 district centers. ○ 2014: The”Seoul Plan 2030” - The Seoul Plan 2030 was developed to revise and supplement the Basic Seoul Urban Plan for 2020. It targeted the year 2030 and an estimated population of 10.2 million, according to Statistics Korea. The Basic Urban Plan for 2020 had independent plans for each of the 12 sectors, and therefore, seeking connection and consistency between the plans would be restricted. Moreover, the information provided was too broad and technical for the general public to understand. In the Seoul Plan 2030, the amount of such information was materially reduced and simplified into 5 key issues and 17 goals. It was firmly built on the actual involvement of people from diverse backgrounds, such as ordinary citizens, experts, city council members, civil servants, and personnel from the Seoul Institute, and the information made accessible and easy to understand. The Plan was established with an emphasis on governance of the wider area within Seoul, in consideration of the relationship between the autonomous districts and the Seoul metropolitan areas. To address the issues related to spatial structure (public demand for better quality of life, the widening wealth gap between regions, expansion and absorption into the Seoul urban area, fierce competition between global megacities etc.), the Plan proposed switching back to the multi-nucleic system, with a focus on various connections to the CBD (Central Business District) and utilization of diverse functions. The multi- nucleic system that the Plan suggested was comprised of 3 city centers (the ancient Hanyang walled city area, Yeongdeungpo/Yeouido, and Gangnam), 7 wider-area centers (Yongsan, Cheongnyangni/Wangsimni, Changdong/Sanggye, Sangam/Susaek, Magok, Gasan/Daerim, and Jamsil), and 12 local centers, with a particular emphasis on the functional connection. |

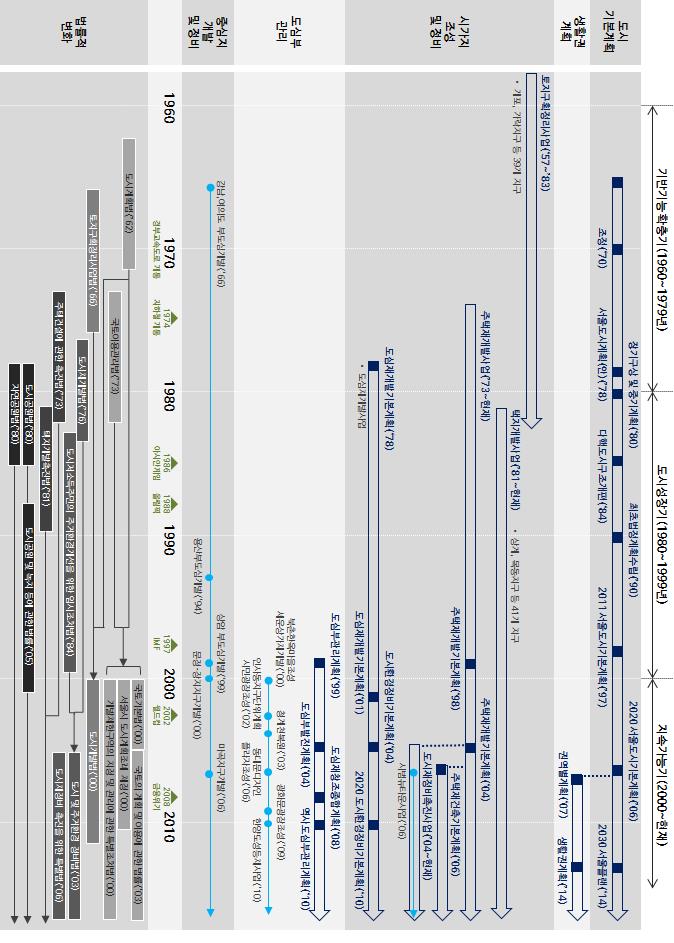

<Figure 1> The History of Urban Planning & Institutional Framework

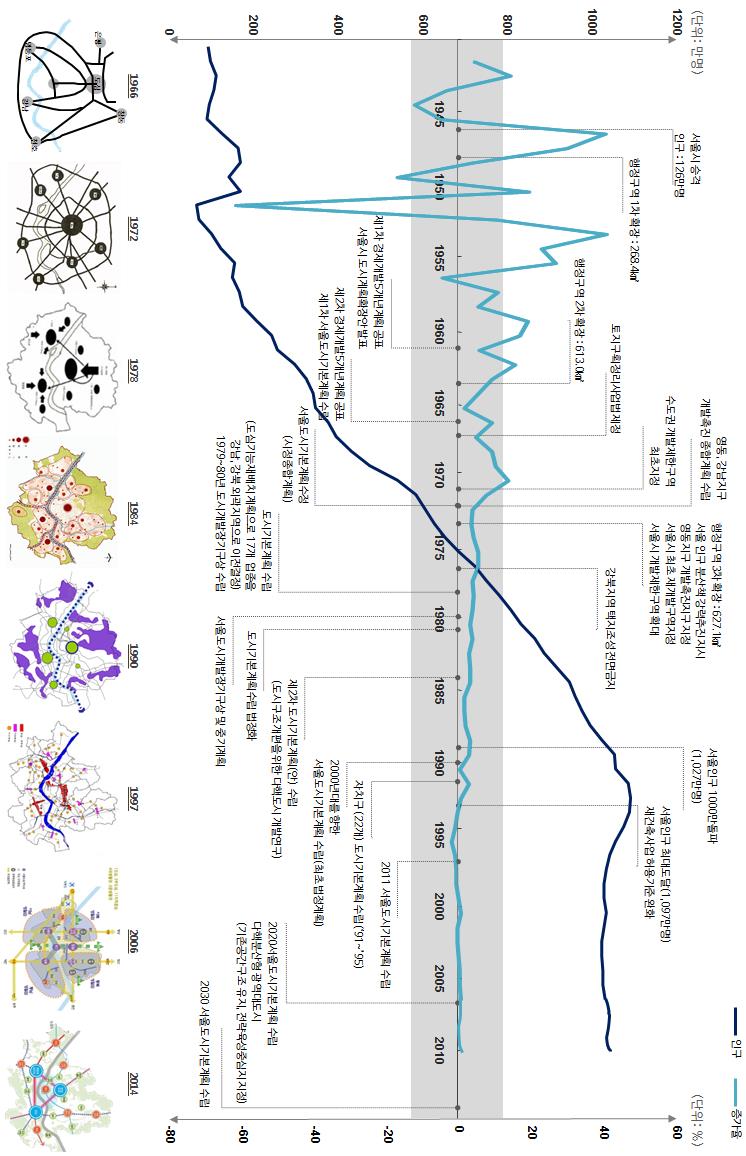

<Figure 2> The History of Seoul’s Urban Planning & Institutional Framework and Changes to the City

Implications

From its appointment as the official capital city for the Joseon Dynasty in 1394 to today’s Republic of Korea, Seoul has served as the heart of the nation. It underwent considerable changes in area under the Japanese colonial government from 1910 to 1945, and suffered the utter destruction of homes, commercial buildings, public institutions and other structures during the Korean War from 1950 to 1953. However, the city rose from its ashes to see incredible growth during the 1960s to the 1980s. The resulting explosive growth in population and expansion of its administrative districts led to many issues such as unauthorized settlements, overcrowding, traffic congestion, and pollution, but the city continued to grow. The emergence of new “towns” in Seongbuk and Gangbuk was accompanied by the construction of many roads, and development in Gangnam began to divert these burdens away from Gangbuk. Development prohibited areas were designated in the Seoul metropolitan area to prevent chaotic expansion.

In the above description of urban planning and management by decade, what the city has done can be seen, as well as the flexibility and effectiveness of the measures used to address issues in various physical, social, and economic situations. Seoul is now focused on new policy direction designed to respond to a new era, demographic changes, and extensive public demands. Developing nations on a similar path as Korea who wish to benchmark and learn from Seoul’s experience will greatly benefit from a review of the following.

First, Seoul is unlikely to witness any more significant population growth due to Korea’s low birth rate and aging population. Population growth will stabilize and Seoul will need to pursue qualitative rather than quantitative growth. However, developing nations in the process of rapid urbanization need both qualitative and quantitative growth. They need to develop the size of their urban areas as well as enhance quality. For this to happen, each city will need to choose the regions that need the most attention and concentrate on qualitative development.

Second, the pursuit of quantitative growth should not lead to reckless abuse of the environment and resources but aim for sustainable development from which future generations can benefit. In the past, Seoul destroyed green areas, filled up open spaces and farmland, and neglected its historical and cultural heritage for urban development. Today, the value of Seoul’s intangible and cultural assets exceeds the value of its tangible resources. It is important to remember that resources are not only for use today but also for future generations, and that continued, systematic management is the key to sustainability.

Third, involving the public in the establishment of any planned action and seeking organic relationships between upper and lower-level plans. Accept that top-down decision-making is a thing of the past and seek to use the bottom-up approach, or a mixture of the two. Development plans must be based on the requests and participation of local residents. Planning of any development should be systematically structured and meticulous, ensuring consistency between plans. At the heart of any urban development plan is its people: it is crucial to improve communication with the constituents of the city, and institute public hearings and other forums of participation in establishing basic urban plans and living spheres.

References

Korea Planners Association, 2005, Urban Planning Theory, Boseonggak.

The Seoul Institute, 2013, Seoul in Map 2013.

Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2009, Study on Evaluation of Urban Planning for Seoul City Center and Reorganization of the Hierarchy.

Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2014, Main Report, Basic Seoul Urban Plan for 2030.

Lee Tae-il, 2001, The Direction of 21st Century Urban Development and the Role of the Public Sector, Korea Land & Housing Corporation.

Relevant Laws

Act on Planning & Use of National Territory

Urban Development Act

Act on Maintenance & Improvement of Urban Areas and Dwelling Conditions for Residents

Urban Planning Ordinance, Seoul Special City

Websites

http://map.naver.com (Naver Map)

http://dmc.seoul.kr (Digital Media City)

http://www.moleg.go.kr (Ministry of Government Legislation)

http://stat.seoul.go.kr (Seoul Statistics)

http://worldcuppark.seoul.go.kr (Seoul World Cup Park)

http://www.seoul.go.kr (City of Seoul)

http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr (Encyclopedia of the Korean Culture)