首尔公园与绿地政策

This report explores the park and green space policies of the Seoul Metropolitan Government by period, from the time Korea opened its ports to the outside world until today. The periods are divided into: modernization and Japanese colonial rule; the first and second republics; the third and fourth republics; the fifth and sixth republics; and local autonomous government administrations elected by popular vote. For each period, this report examines the institutional and spatial changes in urban parks.

Modernization & Japanese Colonial Rule: the Dawn of Urban Parks

Defining Characteristics: mountains and valleys serving as parks (Joseon Dynasty); Independence Park (Open-door Period); destruction of cultural heritage (Japanese colonial government)

The concept of parks and green spaces as planned facilities was introduced as a byproduct of modernization in the late 19th and early 20th century. Of course there had been places that served as parks and green spaces ever since the Kingdom of Joseon moved its capital to today’s Seoul in 1394. The city is surrounded by an inner ring of 4 mountains and an outer ring of another 4 mountains, with the Han River flowing east to west. During the Joseon Dynasty, the walled city was located to the north of the Han, and the significance of the inner ring of 4 mountains (Bugak Mountain, Inwang Mountain, Nak Mountain, and Nam Mountain) was profound as the city walls were built on the ridges of the inner ring. The scholars of old use to visit nearby mountain valleys where they wrote and recited poems for leisure. They were not particularly interested in creating a park in a separate location; they simply visited and admired the beauty of natural scenery. There was another culture of leisure that usually took place in the rear gardens of the mansions of the upper class or the Confucian schools of learning. Because Joseon was strictly bound by social hierarchy, commoners and the lower classes could not dream of a separate place of leisure. At the time, Seoul was located to the north of the Han, whose banks were approximately 4 km away. The city was about 134 km² and populated by 200,000 people.

Korea’s neighbors, China and Japan, opened their doors to the outside world and accepted Western civilization. Naturally, Korea was also influenced by modernization, which began with the seaports and nearby concession areas once Korea opened its doors in 1876. Korean envoys to foreign lands and students studying overseas grew interested in the concept of parks and introduced them to the nation when they returned. Soon, large parks were built in Seoul, Busan, and Incheon, usually by foreign residents in their settlements in Korea. Parks built by Korea included Independence Park by the Independence Association; Pagoda Park, a symbol of enlightenment built under the leadership of the Korean Empire; and Hwaseong Park, or Nam Mountain Park, built by the Japanese settlers.

Launched in 1896, the Independence Association set out to build Independence Park for the purpose of public enlightenment. They used newspapers and Association newsletters to promote the necessity for a park and proposed its construction to the government. In the editorial of an October issue of Independence Newspaper, a writer suggested planting trees around the city walls to create a park. The Association understood the park as a place for commemoration and public enlightenment. The park was originally built on a vacant lot near Independence Gate and Independence Center, but its precise location is not known because Independence Gate had to be moved for road expansion in 1979. Today’s Independence Park opened on August 15, 1992 on the site of Seodaemun Prison in commemoration of the historical significance of Korean independence.

Pagoda Park, the first park in Seoul, is a Western style park built on the site of the ancient Wongak Temple after clearing the homes that were packed tightly around the 10-storey Buddhist temple tower. In 1899, unauthorized houses were demolished to make way for Palgakjeong Pavilion, and then the tower and monuments were erected. At the time, it was owned by the royal family and was not open to the public. After the Japanese colonial government took over, it planted trees and opened the park to the public in 1913. The Kingdom of Joseon understood a park not as a structure to improve urban features but as a symbol of a modern city. On March 1, 1919, the Independence Declaration was recited here, with the Japanese government shutting down the park immediately afterwards.

Nam Mountain Park was also built during the period of open ports. From the outset, it was built for the Japanese and served as the heart of Japanese efforts to transform all Koreans into loyal constituents of imperial Japan. In 1897, the Japanese association of settlers secured 1 hectare of land to the south of their settlement (near today’s Sungeui Girls’ High School) and built a shrine named Hwaseongdae Park, also referred to as Great Nam Mountain Shrine. The park was expanded in 1907 for Gyeongseong Exhibition. Back then, Nam Mountain had several parks: Hwaseongdae Park, Gyeongseong Park and Hanyang Park (near today’s Nam Mountain Tunnel #3). Later, they were collectively called Nam Mountain Park. In 1925, Japan destroyed the shrine for the Korean guardian deity at the top of Nam Mountain. The year before, Japan had already debased the lineage of the Joseon royal house by designating Sajikdan (the altar to the state deities) as a public park. It also banned rituals at Jangchungdan, an altar built in 1900 to inspire patriotic fervor in the people, and turned the area into a park. Changgyeong Palace became a zoo and a botanical garden to humiliate the royal family. Hyochangwon, the tomb of Euibin of the Seong Family and one of the concubines of King Jeongjo, was also turned into a park. As such, the parks built under Japanese colonial rule were not built to provide a place of rest and leisure. They were used as colonial tools to eradicate the native culture and traditions of Korea.

The First & Second Republics (1945 – 1961): the Ordeal for Urban Parks

Parks were abandoned in the chaos created by the Second World War and the destruction of the Korean War. When Seoul was recovered by South Korea, refugees settled in the parks. After the War, these refugees, together with other people in need, were simply trying to survive and ended up in the abandoned parks. The green spaces were damaged during this time, and shacks built. This was the beginning of the poor hillside neighborhoods famously known as the Moon Village (Daldongne), and the green spaces gradually vanished.

During the Rhee Seung-man administration, the government could not afford to invest in parks nor did it have the legal framework to do so. The administration built the statue of Rhee and Unamjeong Pavilion, attempting to justify their presence by transforming Nam Mountain Park into a citizens’ park, ultimately turning it into a personal memorial park for Rhee. Another statue of the ex-president was erected under the name of the Korean Boys’ Club at Pagoda Park.

The Third & Fourth Republics (1961 – 1979): Expansion of Urban Parks

Defining Characteristics: enactment of park-related laws; transformation of cultural and historical sites into neighborhood parks; utilization of parks for propaganda

Park-related laws included the Gyeongseong Town Planning Ordinance established by the Japanese colonial government in 1934, and the Final Notification on Gyeongseong Town Park based on the Ordinance. The laws remained as they were until 1962 when the new Urban Planning Act was promulgated. In 1967, the Parks Act was separated out of the Urban Planning Act and passed as an independent Act. This Parks Act was later divided into 2 separate Acts: the Urban Park Act and the Natural Park Act in 1980. A new type of park – a cemetery park – was introduced, and the national cemetery in Dongjak-dong became the Seoul National Cemetery Park. According to the Basic Urban Park Plan of 1968, the basic system of Seoul’s parks and green spaces, such as neighborhood and children’s parks, are arranged in a radiating ring. After the Urban Park Act was passed in 1980, parks were classified as children’s parks, neighborhood parks, urban natural parks, and cemetery parks. Natural parks were divided into national, provincial, and gun county parks. Green spaces were also divided into green buffer and landscape zones, to be installed as necessary.

<Table 1> Changes in Parks & Green Spaces up to 1990

|

Period |

Description |

|

Opening of the Ports |

Parks were built near the foreign concessions. |

|

Japanese Colonial Rule |

Parks were built as part of urban planning. Nam Mountain Park was turned into a shrine by the Japanese. |

|

Liberation – 1960s |

Nam Mountain Park was turned into a memorial park for Rhee Seung-man. |

|

1960s – 1970s |

1967: The Parks Act was passed. |

|

1980s – 1990 |

1980: The Parks Act was divided into the Urban Park Act and the Natural Park Act. |

One noticeable change after the parks became a part of urban planning was that the 5 cultural and historical sites of Gyeongbok Palace, Changdeok Palace, Changgyeong Palace, Deoksu Palace, and Jongmyo Shrine became neighborhood parks. This was a continuation of the Japanese colonial government’s humiliation of the Korean heritage. Ponds at the royal palaces were used for ice skating, and Changgyeong Palace was degraded into zoo for the recreation of the general public.

<Figure 1> Changgyeongwon Used as a Recreational Facility

It was during this period that land readjustment was being carried out and areas built up. The city grew as the area south of the Han was developed, with the government developing Gangnam and Yeouido to boost economic growth. To make way for public facilities, parks were removed. Nak Mountain Park and Wawoo Park were dismantled, and apartments, to be demolished in later years, were built. Parks were treated as unused land.

Despite the circumstances, some new parks were being built. In 1973, Children’s Grand Park was opened on the old golf course donated by Seoul Country Club. With a children’s center, a zoo, botanical garden, and amusement park, Children’s Grand Park became a favorite place for kids.

Throughout history, political leaders have built statues or memorial towers in parks as a way to advocate ideologies such as nationalism, anti-communism, or modernization. One example is Nakseongdae Park and its statue on the historical site of General Gang Gam-chan. Initially called the May 16th Plaza, Yeouido Plaza was also built in 1971 to boast of Korea’s prowess in national defense. It was used for military parades and religious assemblies until the 1980s when Yeouido Han River Park was built. By then the plaza was called Yeouido Plaza, and most visitors came here to ride bicycles. In 1999, lawns and trees were added and the Plaza was renamed Yeouido Park.

<Figure 3> Yeouido Plaza & Yeouido Park

The development of Gangnam began in earnest in 1971, and parks were added to newly built-up areas in accordance with urban plans. During this time, Dosan Park, Shinsa Park, and Hakdong Park were built. Such parks were about 60,000 m² in size. Large-scale land development was underway at the time, but there was scarcely any consideration for parks and green spaces.

In 1971, development was restricted to the outskirts of Seoul; by 1973, it was applied nationwide. After the North Korean attack on the Presidential Office in 1968, the government sought to secure the space for security reasons, protect the natural environment, and prevent unauthorized urban sprawl. Development prohibited areas still maintain their boundaries and have successfully preserved green space in Seoul. However, they were also the subject of endless civil complaints. In 1998, the prohibition was lifted off some regions by the Kim Dae-jung administration and regulations eased.

The Fifth & Sixth Republics (1979 – 1993): Improvement of Urban Parks

Defining Characteristics: construction of large theme parks, transformation of old sites into parks after relocation, and development of parks on the Han River

While urban dwellers had growing need for cultural areas, the city did not have sufficient land to provide these. Seoul Grand Park (1988) was thus built at the foot of Cheonggye Mountain in Gwacheon, Gyeonggi Province as a recreational area, and included a zoo, botanical garden, sports facilities, the National Museum of Contemporary Art (1986), and Seoul Land (1988). Other theme parks like Seoul Land included Dream Land (1987; in Beon-dong, Gangbuk-gu, the current site of Dream Forest); Lotte World Adventure (1989); and Race Park (1989) in Gwacheon.

When Seoul National University moved from Dongsung-dong, Jongno-gu to Gwanak-gu in 1975, the lot remained vacant. In 1985, Marronnier Park was built, around which many other facilities were developed for culture, art, and performances. No car zone was instituted, while high-end restaurants moved into the area one after the other, turning the area into one of the most popular places and a cultural center for young people.

From 1981, the whole nation started preparing for the Asian Games in 1986 and the Olympics in 1988. To commemorate these international events, Asia Park and Olympic Park were built. After the events, these facilities were open to the public. The government established plans to develop the Han River area; by 1986, open, spacious Han River parks were equipped with sports facilities, natural parks for children, and bicycle paths. Trees taller than a meter were not allowed due to flood risk. In Jamsil and Shingok, reservoirs were made to keep the Han River full at all times and prevent introduction of seawater. Cruise boats, yachts, and other water recreational facilities were provided to maximize use of these parks.

<Figure 5> Olympic Park

<Figure 6> Comprehensive Han River Development

As Seoul expanded and urban functions were dispersed to Gangnam, some of the schools north of the Han were moved to the south. The old school sites were replaced with parks: Gyeongheegung Park (1986) on the site of Seoul High School on Shinmun Road; Boramae Park (1986) on the site of the old Korea Air Force Academy; Son Gi-jeong Park (1990) on the old site of Yangjeong High School; Wonseo Park replaced Hwimun High School; and Susong Park replaced Sukmyung Girls’ High School. When Seodaemun Prison was moved to Euiwang City, Independence Park (1992) was built on the site, and opened on Independence Day. On the old site of the Bureau of Monopoly storage (Dapshimni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu), Gandeme Park (1998) was developed, spanning over 150,000 m2. The old Pilot Factory site (27,000 m2) in Cheonho-dong, Gangdong-gu was turned into Cheonhodong Park, with nature facilities for students.

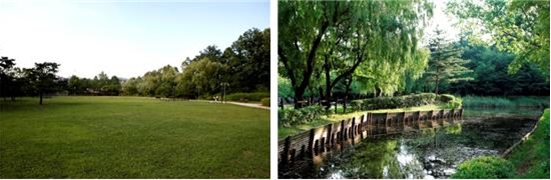

For the leisure of urban dwellers, Yongsan Family Park (1993) was developed on the 90,000 pyeong (0.29 km2) site – golf course and heliport – from the 1 million pyeong (3.3 km2) area used by the 8th USFK Army. Because it has long been a military zone, the greens and water were well preserved, saving much money and time in the development process.

The plans developed at the time were as follows. In 1981, the Comprehensive Han River Development Plan was established to utilize the aggregate and riverside space along the Han. In 1982 and 1987, the 5-year Green Plan for the Capital Area was established; a Study on the Park & Green Space Policies of Seoul and Restoration Plan for Mountains in the Vicinity were developed in 1985 and 1989, respectively.

Local Government Administrations Elected by Popular Vote (after 1993): Ecological Approach to Urban Parks

Defining Characteristics: sustainable development introduced; Nam Mountain Restoration Program

By the 1990s, local autonomy had been introduced. During this period, a new, important concept was introduced: the Environmentally & Socially Sustainable Development (ESSD) was proposed at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil where representatives from governments and private organizations around the world gathered. As much as the environment was important, landscape was another crucial policy aspect.

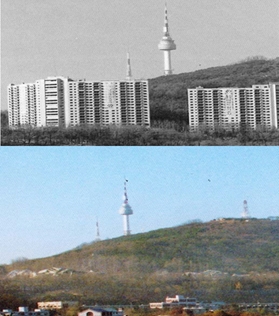

Celebrating its 600th anniversary as the capital city, Seoul launched the Nam Mountain Restoration Program from 1991 to 1998. Apartments housing foreigners at Nam Mountain were removed, the Agency for National Security Planning was moved, the beacon tower was restored, and a botanical garden and traditional Hanok Village were developed at Nam Mountain. From the outset, the plan was a comprehensive one, embracing history, ecology, and urban planning. Relevant departments worked closely with each other and endeavored to communicate with residents, experts, and the media. For the first time, residents were actively involved and the 100 Citizen Committee was created. It was the first plan that considered history, culture, ecology and resident participation as well as urban planning and development. In the meantime, smaller local governments worked to meet the needs of their residents by building small parks, village squares, and sports facilities.

<Figure 8> Nam Mountain Restoration Program (Before & After)

<Table 2> Size of Parks in Seoul after Liberation from Japanese Colonial Rule

|

Year |

Administrative District (㎢) |

Population |

Planned Parks |

Facility Parks |

Facility Park/Planned Park |

||||

|

No. of Parks |

Area |

Area per Person (㎡) |

No. of Parks |

Area |

Area per Person (㎡) |

||||

|

1945 |

136.00 |

90.1 |

142 |

80.00 |

88.75 |

10 |

1.04 |

1.15 |

1.30 |

|

1961 |

268.35 |

257.8 |

124 |

25.22 |

9.79 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

1963 |

613.04 |

325.5 |

136 |

25.04 |

7.69 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

1968 |

N/A |

433.5 |

152 |

55.81 |

12.87 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

1975 |

627.06 |

690.0 |

645 |

158.85 |

23.02 |

387 |

31.70 |

4.59 |

19.96 |

|

1980 |

N/A |

836.7 |

908 |

173.99 |

20.80 |

367 |

41.20 |

4.92 |

23.68 |

|

1985 |

N/A |

960.0 |

1074 |

153.73 |

16.01 |

713 |

48.73 |

5.08 |

31.70 |

|

1990 |

605.42 |

1062.8 |

1325 |

152.37 |

14.34 |

1038 |

89.51 |

8.42 |

58.75 |

|

1995 |

605.77 |

1059.6 |

1404 |

150.84 |

14.24 |

1141 |

105.79 |

9.98 |

70.13 |

|

1999 |

605.52 |

1032.1 |

1423 |

154.23 |

14.94 |

1258 |

130.26 |

12.62 |

84.46 |

|

2010 |

605.27 |

1046.4 |

2531 |

169.05 |

16.16 |

1925 |

145.05 |

13.86 |

86.36 |

|

2014 |

605.21 |

1038.8 |

2782 |

170.08 |

16.37 |

2184 |

148.15 |

14.26 |

87.11 |

|

Source: Seoul Parks Data & Annual Statistics |

|||||||||

As can be seen in the above table, by the 1960s, the total area of Seoul’s administrative district had grown 4.5 times larger than it was when Korea was liberated from Japanese colonial rule, a size that has changed little since that time. Under Japanese rule 142 parks were planned, but only 10 were built. After the Parks Act was passed, hundreds of parks were built from the mid 1970s, and the ratio steadily grew to 70 – 80% in the 1990s.

Term 1, Election by Popular Vote (August 1996 – June 1998)

Defining Characteristics: Seoul Agenda 21, creation of ecoparks, and implementation of the “Great Streets to Walk” program

During this period, the 5-year Plan for Parks & Green Spaces was established by the City of Seoul by Mayor Jo Sun. This plan was marked by a shift from the existing government-led policies that had focused on securing as much land as possible for parks and green spaces to a resident-oriented approach. The new plan included efforts such as securing land for parks and green spaces for residents, upgrading the green spaces and landscape in built-up areas, establishing a foundation for forest vegetation to grow, improving the green space management system, and encouraging resident-involved campaigns for more green space. Environmental policies were also improved during the period. The City of Seoul Framework Ordinance on the Environment and the Environment Charter were enacted, and the Seoul Agenda 21 was formed and implemented in collaboration with resident organizations.

It was also during this period that Yeouido Saetgang Eco Park (1996) and Gildong Eco Park (1996) were opened, introducing the concept of “ecopark”, starting with the natural river restoration program at Yangjae Stream, which resulted in flora and fauna that were not easily seen in a large city.

Various citizens’ campaigns were also begun, such as the No-wall Movement (1996) and the Village Square program. In the same context, activities by NGOs (e.g., Green Korea, Citizen Solidarity for a Beautiful City to Walk) were also active. With the Ordinance on Pedestrian Rights in 1997, the “Create a Beautiful City to Walk” program was pursued from 1998 to 2002, encouraging citizens to be more involved in improving the city’s parks and green spaces. In the meantime, residents continued to plant trees as they felt the growing need for more parks and green spaces in the city.

In addition, Yeouido Plaza, completed in 1971, was transformed into Yeouido Park (1999). Parks were built on sites where other facilities had been located; for instance, the City of Seoul purchased the old site of OB Beer factory and developed Yeongdeungpo Park (1998).

Term 2, Election by Popular Vote (July 1998 – June 2002)

Defining Characteristics: “Plant 10 Million Trees” program, development of Seonyudo Park/Nak Mountain Park/World Cup Park, and increased NGO activities

The “Plant 10 Million Trees” program was the fulfillment of a key promise by Mayor Goh Geon. The aim was to plant trees where there was asphalt and concrete, to turn the grey of the city into green. To reach the goal of planting 10 million trees in the 4 years of the mayor’s term, 2.5 million had to be planted each year. Ten million was an unrealistic goal; moreover, there was not enough land available to plant that many trees. It was thus decided to plant 3 million trees and 7 million shrubs, with 7 million to be planted by the public sector and 3 million by the private sector. Public servants had to go out and hunt for vacant lots; the city launched a campaign urging residents to help them. The city even announced that it would fund tree planting on vacant lots, whether they were on private land or not. The public reacted positively: by 2002, 16.41 million trees were planted in an area of 3.5 km², increasing the percentage of land taken up by parks and green spaces from 25.44% to 26.11%. Olympic Expressway and other parts of Seoul began to turn green, but unfortunately, the ecological effect was not carefully considered.

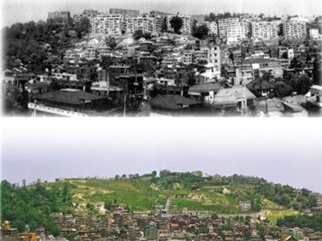

In Seonyudo, the water purification center was moved away, but the facilities were used to make Seonyudo Park. Nak Mountain Park was restored, as it had been damaged by poorly-managed urban development – including construction of 34 5-storey apartment buildings – in the 1960s. Some years later, Wawoo Apartment Building, built on the steep slope of a rocky hill, collapsed. This served as a reason to demolish all apartment buildings at Nak Mountain around 2000 and construct Nak Mountain Park in their place.

<Figure 9> Naksan Park (Before & After Park Construction)

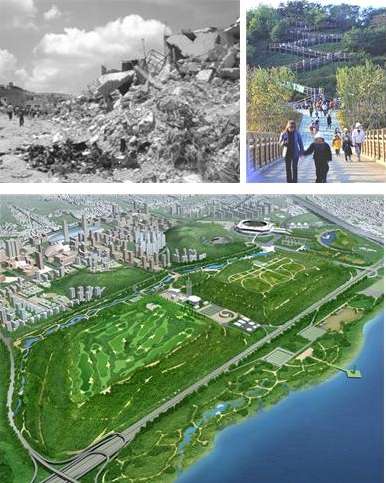

In the process of preparing for the 2002 World Cup, Nanjido (a landfill site) and its vicinity were transformed into the World Cup Park Complex (Peace Park, Sunset Park, Sky Park, and Nanji Stream Park). Other programs were also carried out, including: “Rooftop Parks” (2000 – ), “Urban Green Belts”, “Green Parks & Forests”, “Forest of Hope for Citizens”, and “Green Preservation”.

The advancement of ICT particularly contributed to increasing resident participation and enabling their involvement in government. A good example of this is the Forest Program of 2000. Green Consumer Network and other NGOs also engaged in other environmental activities.

<Figure 10> Residents Involved in Tree Planting Programs

<Figure 11> Transformation of Nanjido into World Cup Park

(Top: Before & After; Bottom: Master Plan)

Term 3, Election by Popular Vote (July 2002 – June 2006)

Defining Characteristics: Restoration of Cheonggye Stream; construction of Seoul Forest, Seoul Square, and Sungnyemun Gate Square, and the “Greener 1 Million Pyeong (3.3 km2)” program

During this period, Mayor Lee Myung-bak pursued the demolition of Cheonggye Stream Overpass and restoration of the stream itself (2003 – 2007). After the 2002 World Cup, the citizens of Seoul were awakened by the nation’s enthusiasm during the games. To meet this enthusiasm, the traffic island in front of City Hall was transformed into a lawn covered square (13,000 m2) in 2004. Sungnyemun Gate Square (7,900 m2) was also developed in 2005.

The city administration had other policies for parks and green spaces, such as the “Greener 1 Million Pyeong (3.3km2)” program. Policy was about reinforcing private-public collaboration and increasing green areas and access by the general public, with an emphasis on resident participation. The “School Parks” program (2006) was undertaken in accordance with this policy, led by a non-government organization called Forests for Life, making 376 schools (364,422 m²) greener. As part of the campaign 16 universities opened their doors, resulting in the expansion of green spaces by 40,360 m².

<Table 3> “Greener 1 Million Pyeong (3.3 km²)” Program (July 2002 – June 2006)

|

|

Project |

Area (m²) |

Remarks |

|

Total |

|

3,546,130 |

= 1.07 million pyeong |

|

Parks |

Urban Natural Parks |

1,772 |

|

|

Neighborhood Parks |

637,243 |

|

|

|

Children’s Parks |

-14,697 |

|

|

|

Cemetery Parks |

-47,463 |

|

|

|

Other Parks (incl. Seoul Forest) |

1,209,813 |

|

|

|

Green Spaces |

School Parks |

364,422 |

|

|

Open-door Universities |

40,360 |

|

|

|

Green Projects by Public Institutions |

15,600 |

|

|

|

Green Walls on Urban Structures |

35,613 |

|

|

|

Beautiful, Green Street to Walk |

42,820 |

|

|

|

Water Features |

87,980 |

|

|

|

Green Riversides |

476,818 |

|

|

|

Green Railroads |

19,011 |

|

|

|

Green Facilities |

52,455 |

|

|

|

Aged Tree Protection Areas |

6,606 |

|

|

|

Broader Green Areas along Streets |

107,285 |

|

|

|

Green Rooftops |

27,224 |

|

|

|

Green Spare Lots |

6,121 |

|

|

|

No-wall Apartments |

1,000 |

|

|

|

Ecology |

Cheonggye Stream Restoration |

375,705 |

|

|

Restoration of Ecological Preservation Area in Bangyi-dong |

58,909 |

|

|

|

Ecological Corridor |

1,210 |

|

|

|

Restoration of Basin Area |

40,322 |

|

<Figure 12> Restoration of Cheonggye Stream (Before & After)

<Figure 13> Seoul Forest

Thanks to the contribution and participation of residents, Seoul Green Trust was established in 2003, and Seoul Forest (2005) was developed in a 1.15 km2 area in Ttukseom in a private-public partnership. Unlike other parks built solely by the public, the Forest was built through the efforts of residents who planted trees and also of NGOs that worked with residents to maintain the forest. This was a whole new approach to park management. The Forest was fragmented in many places due to roads, but they were planned as separate units: an eco forest, citizen space, learning space, and wetland, completed by some 420,000 trees. The makers of the Forest placed particular focus on ecological significance of the convergence of the Han River, Jungnang Stream, and Cheonggye Stream. With diverse programs and activities for people, it has now become one of the most loved places in the city.

With introduction of the “Wellness” concept and the 5-day work week, people began to have more time for leisure. In 2005, the Green Seoul Bureau was established in the city government, and the importance to the public sector of parks and green spaces grew. Nadeuri Park (Mangwu-dong, Jungnang-gu), Pureun Arboretum (Hang-dong, Guro-gu), and Amsa Ecological History Park (Amsa-dong) were also built around this time. In addition, another program was set up to build a park in each dong district, such as the neighborhood parks in Munjeong-dong, Songpa-gu built on an abandoned railroad lot.

The city endeavored to supply more green spaces to strike a regional balance. Green spaces isolated by roads were connected to restore the ecosystem and greenbelt continuity.

Term 4 and 5, Election by Popular Vote (July 2006 – August 2011)

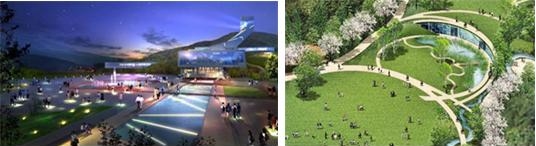

Defining Characteristics: Dream Forest for balanced development of Gangnam & Gangbuk; Han River Renaissance & Nam Mountain Renaissance

During this period when Mayor Oh Se-hun served 2 consecutive terms, the Han River Renaissance and Nam Mountain Renaissance were pursued. The city aimed to achieve a balanced development of Gangnam and Gangbuk and implemented such policies as creating large and neighborhood parks in Gangbuk, recreating parks with resident participation, and encouraging residents to participate via the “Seoul Oasis”. Relatively speaking, the urban conditions in Gangbuk were poor, and programs were introduced to improve things. One of these programs was development of Dream Forest (2009), about 663,000 m2 in area, on the old site of Dream Land. An observation tower, cultural center, lake, pavilion, and Wolgwang Waterfall are located inside the Forest. Sejong Center for the Performing Arts provides performances and exhibitions at the Forest, attracting many visitors. These represent effective ways of resolving complaints about the existing parks with strategic management plans that are well-received by the public.

<Figure 14> Dream Forest

West Seoul Lake Park (2009, 225,000 m2) was developed on the site of Shinwol Water Purification Center in Yangcheon-gu. The grounds around the water treatment facility, closed in 2003, were turned into a theme park. In Dobong-gu, another theme park was built called Seoul Changpowon (53,000 m2) with 12 themes, such as irises, medicinal plants, and wetlands.

Some deteriorating children’s parks were also targeted and renovated. For instance, KRW 87.68 billion was spent on the “Children’s Parks of Imagination” program (2008 – 2010), by which some 300 outdated children’s parks were renovated. Eco-friendly materials were used for children’s safety, and local residents and their kids participated in the planning, construction and management of the parks. This is in stark contrast to the rigid park development methods of the 1970s and 1980s, demonstrating a shift in awareness that the needs and desires of the actual users should be reflected in the making of the parks.

<Figure 15> Park Involved in “Children’s Parks of Imagination” (Before & After)

Mayor Oh Se-hun introduced policies to increase the brand value of Seoul and achieve a target of attracting 12 million tourists. Festivals were held by season, and international energy and environmental events, such as C40, were hosted in Seoul to breathe more vitality into the city. Greenery was deemed especially significant in the city’s landscape; to make it greener, Seoul introduced a program of turning rooftops of privately-owned buildings green.

<Figure 16> Green Rooftop (Before & After)

From 2009, the city embarked on the Nam Mountain Renaissance project. With “recovery” and “communication” as the two overarching concepts, the Nam Mountain Renaissance Master Plan employed 6 strategies to develop Nam Mountain as a brand. The city also established plans to build 4 neighborhood parks in Jangchung, Yejang, Hoehyeon, and Hannam, and develop the vicinity of Seoul N Tower to create a new source for culture at Nam Mountain.

<Figure 17> Nam Mountain Renaissance Plan (Before & After)

As part of the Han River Renaissance project that started in 2006, the floating Islands Sebit was developed at Banpo District of the citizens’ parks; at Yeouido District, unique themes were given to the park, for example, by installing fountains. Bicycle paths were created and access roads improved at the interchange to allow easier access. Some of the shoreline embankments were restored to their natural state, but the effects were minimal. Moreover, the nightscape programs caused disruptions to the ecosystem and wildlife habitats.

Term 6, Election by Popular Vote (October 2011 – Today)

Defining Characteristics: Completion of mountain paths and tracks; inspection and measures for slope stability; development of parks by lifecycle

After the disastrous landslide from Umyeon Mountain in July 2011, Mayor Park Won-sun and his administration became acutely aware of the danger and reinforced the slopes. The city also implemented urban safety policies. Because mountains act as doctors keeping Seoul and its citizens healthy, tracks and paths were built on the mountains in the city and those forming the outer rings to promote walking and hiking. Other programs were also put in place such as “Green Walls”, “Open Green Apartments”, and “School Parks”.

<Figure 18> Open Green Apartments (Before & After)

As for the Han River, the 2030 Natural Restoration Plan for the Han River was established to restore the natural waterway. Natural embankments and wetlands are part of the plan, so as to create an environment favorable to both humans and wildlife. In 2013, the city announced its “Green City Declaration” with public landscapers and has since been working on changing the traditional park paradigm, to create a “park city” that goes beyond traditional park boundaries to embrace all possible spaces, from streets, alleys, squares, rooftops, and even walls.

Well aware of the value of urban farming, the city designed public vegetable gardens on Nodeul Island. Today, residents take the lead in managing these green spaces; with examples including the Citizen Gardener and Adopt-a-Tree/Park programs. There are also green spaces specifically designed to be included in daily life, such as healing parks by life cycle; 80 vegetable gardens at schools and social welfare facilities; Ssamji Madang; forests for babies; and “customized” neighborhood hill parks. After relocation of the USFK base in Yongsan is complete, Yongsan Park (2.57 km2) at the center of the north-south green belt will be the ecological heart of Seoul.

Major Policy Changes

Changes From Government-led to Private-led

From Japanese colonial rule to military dictatorship, parks were treated as tools to promote ideology to the people. The rulers erected statues of themselves and commemorative structures across the country, and in the process damaged the cultural and historical heritage. When democratic governments began being elected, public awareness increased and residents began to participate in the development and management of parks. In turn, they could access the services they wanted and needed. Today, parks and squares are not only for leisure and recreation but also for demonstration of their rights as citizens.

From Sacrifice of Nature to Peaceful Cohabitation

At a time when economic growth was the priority, parks were deemed as unused land, a place where buildings could be erected as needed. As cities grew, green areas slowly disappeared and vacant lots were hard to come by. In recent years however, air pollution, health issues, and demands for leisure reminded people of the significance of parks and green spaces. Over time, they began making the effort to discover and visit natural environments, and realized that development should not be in a conflicting relationship with parks, but at peace. As a result, the city adopted such concepts as biotope areas, mandatory percentages of park and green space in redevelopment projects, and “green” initiatives for privately-owned buildings. As part of the special measures taken by the Mayor of Seoul, public institutions in Seoul are required to ensure a certain level of biotope area from July 2004. From 2006, this requirement also applied to the housing performance rating system of the Ministry of Construction & Transportation. Because the index is incorporated in environmental impact assessment, the relevant authorities are encouraged to carefully consider and expand the percentage of natural ground and waterfront areas in the city, the ratio of pervious surfaces, and man-made green spaces (e.g., green rooftops).

From Damage to Preservation of the Ecosystem

If other types of life cannot survive in the city, people are not likely to lead healthy lives either. The living environment can only be healthy when birds, insects and other animal life thrive in the city. That is why it was important to remove Cheonggye Overpass, restore Nam Mountain to its natural state, designate environmental preservation areas, and improve the environment so that people can live alongside other forms of life in peace. Preserving the ecosystem is to protect the living environment of the people. The areas rich in biodiversity or with beautiful landscapes are therefore designated for preservation and are managed in a systematic manner. These areas include: Bamseom Island on the Han River, designated as a Ramsar wetland in June 2012; wetlands in Dunchon-dong and Bangyi-dong; Tan Stream; Wonteo Valley at Cheonggye Mountain; and the royal garden at Changdeok Palace.

Discontinued & Interrupted Policies

Under the dictatorships, parks were used to idolize an individual or promote power. The democratic governments did work to meet the needs of their citizens, but many plans were discontinued or isolated in nature as candidates made promises to win elections and had to finish them before they left office. Naturally, the plans were more focused on quantity than quality.

Furthermore, rising land prices in the city made it difficult to secure the land necessary for new parks and green spaces. Seoul was slowly seeing less and less land development and housing construction projects over time, allowing the focus to shift from quantity to quality. There are many lots that were designated for park construction, but nothing has been done for a long time on those sites due to the failure to secure funding. When designation is removed from such sites in 2020 pursuant to the Sunset Law, the area for parks will be drastically reduced.

It is therefore crucial to find ways to secure land that is available, while coming up with further plans to improve the park services and ecosystem therein. Park development projects need to focus less on facilities and more on green areas for the health of both residents and the city as a whole as well as on the aesthetic and environmental aspects. It should also be noted that securing sufficient funding is critical for land compensation and improving the cost structure for park maintenance.

References

Gang Shin-yong and Jang Yun-hwan, Urban Parks in Modern Korea, Daewangsa, 2004.

Ministry of Construction & Transportation, Act on Urban Parks, Greenbelts, Etc.

Ministry of Construction & Transportation, Guidelines on Specific Standards & Requirements for Urban Parks & Green Spaces by Type.

Kim Gi-ho and Mun Guk-hyeon, Green Way, the Life Source of a City, Random House Joongang, January 2006.

Kim Yong-gi, “Comparison of Park & Green Space Policy and Systems of Seoul with Other Overseas Cities”, Journal of Korean Institute of Gardening, Issue 3, Volume 22, (October 1994).

Kim Won-ju, The Plan to Create Neighborhood Parks & Green Spaces via Citizen Participation, The Seoul Development Institute, 2007.

Park Gil-yong, “Sustainable Urban Park & Green Space Policies – a Focus on Seoul”, Koreanisch-Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer Sozlaiwssenschaften, Issue 2, Volume 13 (Winter 2003).

Park Yul-jin, “Statistical Study of the Changes in Urban Parks & Green Spaces”, Journal of the Korea Institute of Forest Recreation Welfare, Issue 1, Volume 14, 2010.

Park In-jae and Lee Jae-geun, “Study on the Changes in Urban Parks in Seoul”, Journal of Korean Institute of Gardening, Issue 4, Volume 20 (December 2002).

Seo Yeong-ae, Landscape of Historical Importance: Nam Mountain in Seoul, Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, 2015.

Seoul Metropolitan Government, the City of Seoul Ordinance on Urban Greening.

Son Jeong-mok, Urban Planning in Seoul, Hanwool, 2007.

Yang Byeong-yi, “Study of the 50-year History of Landscape in Korea”, Academic Seminar for the 40th Anniversary of Seoul National University, 1986.

Lee Geun-hyang, “The Private-Public Cooperative Operational System for Seoul Forest – the Park Created by Seoul Green Trust and the Citizens”, Seoul Green Trust Urban Forest Symposium V, Collection, November 2006.

Jang Yun-hwan, How Urban Parks Survived & Settled in Chaotic Times in Seoul, Master’s Dissertation, Kyungpook National University, 2001.

Choi Gi-su, “Seoul, the 600-year Old Capital City: Diagnosis of its Urban Environment”, Environment Landscape Architecture, January 1994 Issue, Volume 69.

Choi Yong-ho, “Seoul’s Park & Green Space Policies”, Internal Data, Green Seoul Bureau, Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2006.

Ha Hye-gyeong, “Study on Citizen Participation in the Park and Green Space Administration of Seoul”, Master’s Dissertation, University of Seoul, February 2005.

Hwang Gi-won, Spatial Changes of the 20th Century, The Seoul Development Institute, 2001.