[Torontoist] How (Not) To Restore Urban Waterways

How (Not) To Restore Urban Waterways: What Toronto can learn from Seoul.

By Emily Macrae September 27, 2016 at 9:00 am

Public Works looks at public space, urban design, and city-building innovations from around the world, and considers what Toronto might learn from them.

See this original article

As Toronto city councillors debate the next steps of a proposal to cover train tracks with a park, South Korea’s capital city demonstrates the possibilities and pitfalls of bringing buried waterways back to the surface.

Today, the Cheonggyecheon stream flows through almost 11 kilometres of downtown Seoul, but it spent much of the last century covered in concrete. As the city grew, the stream became increasingly polluted, until it was paved over in 1958.

When an expressway was built along the stream’s course in 1971, it seemed like local politicians had literally prioritized the circulation of vehicles over the water cycle.

However, between 2003 and 2005, the city invested $900 million (U.S.) to restore the stream and remove the elevated highway. Today, water once again winds through the downtown while the source is anchored by a large public plaza. Although at first glance the project seems like an inspirational combination of urban planning and engineering, it is not without its flaws. Instead, the long-term consequences of the stream restoration offer lessons in the design and implementation of public spaces in dense, urban areas.

From an environmental perspective, the stream is only a partial victory. As activist and academic Eunseon Park explains, the stream bed is made of concrete, which limits integration with surrounding ecosystems and contributes to an expensive algae problem. Socially, the project lacked public consultation and was instead pushed through by the mayor, intent on cementing his legacy before entering national politics.

The restoration also neglects the historic features of the area and is instead punctuated by generic public art from global pop art icons Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. The economic legacy of the project is equally questionable, since the stream displaced a flourishing flea market whose vendors were ultimately unable to find a new place to set up shop downtown.

Despite these drawbacks, experiences from Seoul also reveal the benefits of reintroducing waterways to urban environments. Today, more than 10 years since the restoration of the stream was completed, more than 60,000 people visit each day. The fact that the vast majority of these visitors are residents, rather than tourists, suggests that the stream meets a local need, rather than simply attracting international attention.

The reintroduction of the stream also forced traffic to be rerouted, discouraging car use in the downtown and increasing bus ridership by 15 per cent within the first five years alone. This shift in transportation habits has had positive impacts on air quality, public health, and congestion. The stream has become a haven for local plants and wildlife, increasing biodiversity in the city and reducing the urban heat island effect. Culturally, more than 20 bridges knit together neighbourhoods north and south of the stream by creating frequent crossing points for both pedestrians and vehicles.

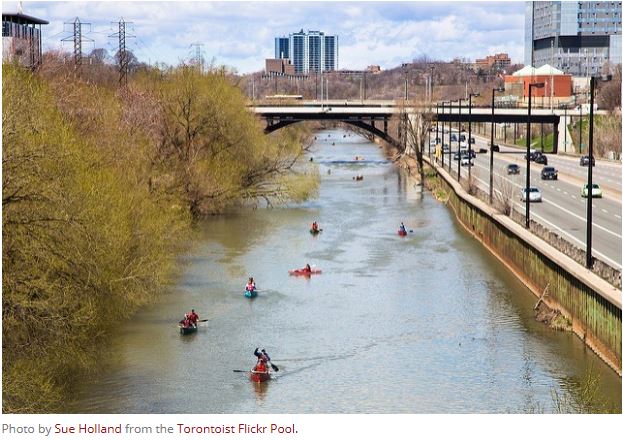

The parallels between Seoul and Toronto are hard to ignore. Although in recent years the Don River has become a conservation success story, Toronto’s urban fabric is defined by traces of smaller waterways that were initially buried to reduce the spread of disease and make way for development. They continue to leave their mark on flooded basements, unexpected dead ends, and strange slopes throughout the city.

Lost Rivers is a project of Toronto Green Community that aims to acquaint Torontonians with the watershed beneath our feet. Since 1995, Lost Rivers has led annual walking tours of more than 12 creeks and streams throughout the city for upwards of 18,000 participants. Raising awareness of the routes that connect Lake Ontario to distant corners of the city is only the first step in creating communities that respond to and respect their natural settings.

Although uncovering streams is a complex and costly undertaking, Toronto can also learn from Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon about balancing social, environmental, and economic outcomes in the development of other iconic public spaces. As discussions about Rail Deck Park continue, Seoul proves that large-scale parks projects must be grounded in citizens’ needs and integrate local heritage without cutting corners when it comes to environmental impact.