Reducción de Viajes con Coche: Gestión de la Demanda de Transporte

Policy Implementation Period

Up until 1960s, public transportation had played a crucial role as major urban transportation. However, since 1970s a sharp rise in the number of personal cars coupled with continuous economic growth had caused severe traffic congestion. Transportation Demand Management (TDM), which emerged as a strategy to resolve such traffic congestion, could be seen as an alternative approach to optimize the transportation demand by changing and attuning the demand patterns for each transportation means and time slot, which broke away from conventional approaches including transportation policy focusing on supply-side policy.

Since the introduction of congestion impact fee system in 1990s, various types of TDM approaches have been implemented including Namsan tunnel congestion charge, the parking threshold, and mandatory charging of parking lot fees in 1990s and Weekly No-Driving Day Program and car sharing in 2000s on a gradual basis. Figure 1 gives chronological view on Seoul’s TDM programs.

Since the introduction of congestion impact fee system in 1990s, various types of TDM approaches have been implemented including Namsan tunnel congestion charge, the parking threshold, and mandatory charging of parking lot fees in 1990s and Weekly No-Driving Day Program and car sharing in 2000s on a gradual basis. Figure 1 gives chronological view on Seoul’s TDM programs.

Figure 1. Seoul’s TDM Programs by Year

Source: Seoul Archive 2015(https://seoulsolution.kr)

Background Information

From 1970s to 1990s, Korea’s transportation policy was tuned to the supply side, with much emphasis on construction and expansion of road networks to make up for the absolute shortfall in capacity. In that period, gap between supply and demand widened as rapid economic development led to sharp rise in transportation demand.

The number of personal cars registered in Korea had risen eight fold to 2,075,000 units in 1990s from 249,000 units in 1980 but 20% of road expansion for the same period fell far short of meeting the explosive demand. For those reasons even during the 1990s tremendous amount of efforts had been made to expand facilities by promoting private investment in transportation and construction at the government level.

In Seoul alone, the number of registered cars had risen to two million units in 1995 from one million in 1990 in just five years. Although expansion of street networks had been continuously promoted due to a soaring rise in the number of cars, road supply failed to catch up with the demand. Therefore, traffic congestion in the downtown in 1980s had been part of daily routine and in the 1990s traffic congestion in the major arterial roads had become more serious. In order to provide traffic facilities, large-scale road constructions had been conducted including expanding urban arterial roads and interregional expressway network, connecting City of Seoul and new town.

Despite such a massive road expansion, the traffic congestion aggravated even further due to a soaring rise in the number of personal cars even after 1990s, leading to a continuous slower travel speed in Seoul. Advanced cities across the world also shared the view that additional supply of traffic facilities alone would not solve traffic congestion. In line with the times, the SMG has introduced TDM since 1990s as a strategy to mitigate traffic congestion.

In the era of low-carbon green growth when the importance of sustainable development has been highlighted in order to reduce green gas, TDM methods and their importance have become ever more important. TDM, in general, refers to various policy attempts which change the selection patterns of passengers’ choice of transport means, reduce number of car travels, and induce effective use of passenger cars. The Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act defines TDM a policy mitigating traffic congestion by inducing reduced share of car travel, dispersing trips in terms of time and space, and shifting travel mode share. TDM is defined in ‘the Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act’ as a policy designed to mitigate traffic congestion by reducing car travel, and encouraging people to utilize forms of transport other than their personal vehicles. Act No.10599 --‘The Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act’, Chapter 4 Traffic Demand Management, Article 33 Implementation of Traffic Demand Management ( ) stipulates mayors of each city may implement TDM for smooth traffic flow, air quality, efficient use of transportation facilities at certain area within the city’s jurisdictional boundary by reflecting public opinions through the public hearings.

While observing the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act, the SMG has developed and implemented various TDM programs, reflecting urban characteristics of Seoul.

The number of personal cars registered in Korea had risen eight fold to 2,075,000 units in 1990s from 249,000 units in 1980 but 20% of road expansion for the same period fell far short of meeting the explosive demand. For those reasons even during the 1990s tremendous amount of efforts had been made to expand facilities by promoting private investment in transportation and construction at the government level.

In Seoul alone, the number of registered cars had risen to two million units in 1995 from one million in 1990 in just five years. Although expansion of street networks had been continuously promoted due to a soaring rise in the number of cars, road supply failed to catch up with the demand. Therefore, traffic congestion in the downtown in 1980s had been part of daily routine and in the 1990s traffic congestion in the major arterial roads had become more serious. In order to provide traffic facilities, large-scale road constructions had been conducted including expanding urban arterial roads and interregional expressway network, connecting City of Seoul and new town.

Despite such a massive road expansion, the traffic congestion aggravated even further due to a soaring rise in the number of personal cars even after 1990s, leading to a continuous slower travel speed in Seoul. Advanced cities across the world also shared the view that additional supply of traffic facilities alone would not solve traffic congestion. In line with the times, the SMG has introduced TDM since 1990s as a strategy to mitigate traffic congestion.

In the era of low-carbon green growth when the importance of sustainable development has been highlighted in order to reduce green gas, TDM methods and their importance have become ever more important. TDM, in general, refers to various policy attempts which change the selection patterns of passengers’ choice of transport means, reduce number of car travels, and induce effective use of passenger cars. The Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act defines TDM a policy mitigating traffic congestion by inducing reduced share of car travel, dispersing trips in terms of time and space, and shifting travel mode share. TDM is defined in ‘the Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act’ as a policy designed to mitigate traffic congestion by reducing car travel, and encouraging people to utilize forms of transport other than their personal vehicles. Act No.10599 --‘The Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act’, Chapter 4 Traffic Demand Management, Article 33 Implementation of Traffic Demand Management ( ) stipulates mayors of each city may implement TDM for smooth traffic flow, air quality, efficient use of transportation facilities at certain area within the city’s jurisdictional boundary by reflecting public opinions through the public hearings.

While observing the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act, the SMG has developed and implemented various TDM programs, reflecting urban characteristics of Seoul.

The Importance of the Policy

Korea was not alone in its heavy dependence on the supply of transportation facilities as a means to resolving urban transportation challenges. Advanced industries including the U.S. and U.K. had taken supply-focused approaches, focusing on accommodating rising demand until 1980s. As doubts had been broadly raised on the previous transportation plan method and direction of transportation policy in the U.S. (in the 1980s) and the U.K (in the late 1990s), limitations in the supply-oriented approach had been widely accepted.

Such doubts had been supported by theories: ‘The law of traffic’ explained in 1977 by Anthony Downs 1977 and ‘induced traffic’ conceptualized by Mogridge MJH and Williams HCWL in 1985. According to those theories, expansion of roads or construction of new roads at a severely congested region will have temporary effect, leading to a faster travel speed for a while. However, improved road service will induce more use of car travel of people who have refrained to do so due to heavy congestion. Latent demand caused by heavy congestion will convert to a real demand to the pre-expansion or pre-construction level, once congestion gets relieved.

Even without theoretical supports, the general public in the U.S shared the idea of “We can’t build our way out of congestion.” In the U.K., people expressed their understanding on the limitations in road construction with the term ‘New Realism.’ Both meant roads might not be constantly constructed to meet the rising demand for cars

To keep abreast of global trend, SMG introduced TDM. TDM could be longer perspective approach than supply-oriented one in the sense that it could prevent and control heavy dependence on cars by changing traffic pattern when implemented effectively.

When is a good timing to shift from supply-oriented policy to demand-oriented one in the case of developing countries whose road rate is noticeably low? Isn’t it necessary to focus more on supply when traffic facilities are in absolute shortage? These are questions that could be raised when discussing TDM. The right answer depends on what level of travel mode share is determined to be optimal. The crucial thing is that supply and demand is not a matter of choice between the two. If supply is done enough, it greatly matters to manage demand and supply properly.

Some argued that congestion impact fee system did not work. Recently, it’s been said that there has been noticeable effect by combining it with TDM involving/for companies.

Such doubts had been supported by theories: ‘The law of traffic’ explained in 1977 by Anthony Downs 1977 and ‘induced traffic’ conceptualized by Mogridge MJH and Williams HCWL in 1985. According to those theories, expansion of roads or construction of new roads at a severely congested region will have temporary effect, leading to a faster travel speed for a while. However, improved road service will induce more use of car travel of people who have refrained to do so due to heavy congestion. Latent demand caused by heavy congestion will convert to a real demand to the pre-expansion or pre-construction level, once congestion gets relieved.

Even without theoretical supports, the general public in the U.S shared the idea of “We can’t build our way out of congestion.” In the U.K., people expressed their understanding on the limitations in road construction with the term ‘New Realism.’ Both meant roads might not be constantly constructed to meet the rising demand for cars

To keep abreast of global trend, SMG introduced TDM. TDM could be longer perspective approach than supply-oriented one in the sense that it could prevent and control heavy dependence on cars by changing traffic pattern when implemented effectively.

When is a good timing to shift from supply-oriented policy to demand-oriented one in the case of developing countries whose road rate is noticeably low? Isn’t it necessary to focus more on supply when traffic facilities are in absolute shortage? These are questions that could be raised when discussing TDM. The right answer depends on what level of travel mode share is determined to be optimal. The crucial thing is that supply and demand is not a matter of choice between the two. If supply is done enough, it greatly matters to manage demand and supply properly.

Some argued that congestion impact fee system did not work. Recently, it’s been said that there has been noticeable effect by combining it with TDM involving/for companies.

Relevance with Other Policies

While keeping in mind of the limitations in the supply-focused transportation policy including expansion of transportation facilities and construction of roads, policy concept of transportation system management (TSM) emerged. Transportation system includes both physical system and passenger, the human element.

Transportation system management could be divided into two: transport system management (TSM) which highlights effective operation of traffic facilities, and transport demand management (TDM) which focuses on managing demand of road use by transportation facility users. Some management approach belongs both to TSM and TDM as demand for cars could drop by changing the patterns of using facilities. For example, ‘bus-only lanes’ reduces demand and supply of transportation, which was designed to induce the personal car owners to use bus by improving bus service.

TSM and TDM by nature have common denominators and various approaches belonging to each system management have synergy effect to each other. If those mutually beneficial approaches are combined and implemented after thoroughly checking such relations with various approaches, it will bring about much better outcome than implementing them separately. The combination of ‘bus only lanes’ and ‘bus priority signal system’ could create synergy effect. Along with the combined approaches, when the time-saving transit center, real-time bus information, bus only lanes violation enforcement are well utilized so the reduced bus travel time is big enough, then majority of car owners will prefer taking bus as desired.

After all, a series of TDM approaches have close relations with policies which make public transportation more appealing while making the use of personal cars harder and inconvenient. As mentioned earlier (part 3), it is such an irony that TDM is closely related to supply-oriented transport policies. That is because TDM could contain negative effect of additional supply only when implemented along with supply-focused transport policy especially when the supply is unavoidable.

Transportation system management could be divided into two: transport system management (TSM) which highlights effective operation of traffic facilities, and transport demand management (TDM) which focuses on managing demand of road use by transportation facility users. Some management approach belongs both to TSM and TDM as demand for cars could drop by changing the patterns of using facilities. For example, ‘bus-only lanes’ reduces demand and supply of transportation, which was designed to induce the personal car owners to use bus by improving bus service.

TSM and TDM by nature have common denominators and various approaches belonging to each system management have synergy effect to each other. If those mutually beneficial approaches are combined and implemented after thoroughly checking such relations with various approaches, it will bring about much better outcome than implementing them separately. The combination of ‘bus only lanes’ and ‘bus priority signal system’ could create synergy effect. Along with the combined approaches, when the time-saving transit center, real-time bus information, bus only lanes violation enforcement are well utilized so the reduced bus travel time is big enough, then majority of car owners will prefer taking bus as desired.

After all, a series of TDM approaches have close relations with policies which make public transportation more appealing while making the use of personal cars harder and inconvenient. As mentioned earlier (part 3), it is such an irony that TDM is closely related to supply-oriented transport policies. That is because TDM could contain negative effect of additional supply only when implemented along with supply-focused transport policy especially when the supply is unavoidable.

Policy Objectives and Processes

TDM has been designed to induce changes in individual’s decision on means of transportation, travel time, traffic volume and travel area by changing overall elements affecting individual’s decision making. Ultimately, TDM aims to resolve traffic congestion, change it into sustainable transportation system which leaves less negative impact on the environment and society and maintains the sustainability by changing the quantity and structure of transportation demand,

Policy Contents

Congestion Impact Fee System

In the 1980s and 1990s, transportation problems got severer as the increase in transportation facilities failed to keep up with the skyrocketing rise in transportation demand, resulted from sharp rise in the number of personal cars and improved public income level. In particular, buildings including wedding halls and department stores caused a heavy traffic demand at specific hours and caused a serious congestion, which led to significant social and economic costs. The congestion impact fee system, a part of Seoul’s TDM policy, was introduced in 1990 in order to levy burdens to buildings causing massive transportation demand and to utilize the money in expanding and improving transportation facilities.

Enforcing the congestion impact fee, as defined by the Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act, resulted in facility owners paying a fee in accordance with the “causer-pays” principle so as to indirectly rein in the concentration of facilities that cause congestion in the city and to secure funds for improvement of the city traffic situation. While some facility owners have objected to this additional financial burden, public consensus was reached on the necessity of a system designed to reduce the social and economic losses caused by the traffic congestion and to provide quality transportation services to the public.

The legal basis for the congestion impact fee was in the Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act revised and promulgated on January 13, 1990. The target areas were cities with populations of 100,000 or more and cities where the Minister of Land, Infrastructure and Transport acknowledged it necessary to levy the Act. The levied fees were deposited in a special account for the local city transportation program, to be used to improve transportation systems and facilities such as implementation of bus-only lanes.

The City of Seoul fundamentally follows the enforcement rules concerning the impact fee as prescribed in the Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act, but it also set up its own ways to levy the fees, which are calculated by multiplying total floor area of the facilities, the unit congestion impact fee, and the congestion coefficient. The unit congestion impact fee is 700 to 800 Korean won per m² of floor area; the congestion coefficient varies by location and use of the facilities – from at the minimum 0.47 for a factory to at the maximum 10.92 for a department store. The congestion impact fee is levied on owners of facilities with a total floor area of 1,000 m² or more. In the event a facility is owned by multiple entities, each pays proportional to their share of ownership.

Table 1. SMG, Ordinance on the Congestion Impact Fee Discount

| Total floor area of the facilities | (Congestion Impact) Fee | |

| 3,000 m² and smaller | Area smaller than 3,000 m² × 700 × congestion coefficient | |

| Over 3,000 m² ~ 30,000 m² and bigger |

2014 | Area smaller than 3,000 m² × ₩ 700× congestion coefficient |

| 2015 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2016 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2017 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2018 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2019 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2020 ~ | × congestion coefficient | |

| Over 30,000 m² | 2014 | × congestion coefficient |

| 2015 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2016 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2017 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2018 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2019 | × congestion coefficient | |

| 2020~ | × congestion coefficient | |

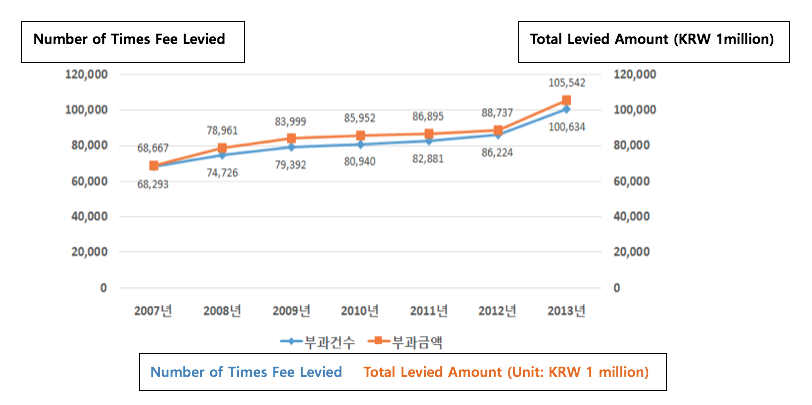

In Seoul, the number of facilities paying the congestion impact fee and the amount collected has grown every year. Since 2007 when data on the collection of congestion impact fee started to be established, the number of times the fee was levied reached 100,634 times in 2013, and the amount totaled about ₩ 105.542 billion.

Figure 2. Congestion Impact Fees Levied in Seoul

Source: The Korea Transport Institute (2014)

Transportation Demand Management Policy for Companies

To further drive the congestion impact fee system and encourage companies to get on board, the City of Seoul introduced a TDM system for companies, designed to get them involved in reducing traffic volume on a voluntary basis. This allows companies to participate in traffic volume reduction programs, the outcome of which determines the discount on (or even exemption from) the congestion impact fee for which the business is responsible. In the early days of introducing the program in 1995, companies were required to impose parking fees on cars using their parking facilities, but this mandatory requirement was soon abolished in 1999. After the abolishment, it became easier to participate in the program or implement the program, thus the participation rate rose. This TDM for companies is positive for individual residents, as it targets the facilities and companies that create large traffic volumes.

The TDM policy for companies stems from Regulation 15, adopted as part of Southern California’s Clean Air Act. The major difference is that California imposes penalties on non-complying companies but Seoul offers discounts/incentives instead for those that participate.

This system was first proposed in the Study on Transportation Demand Management in Seoul conducted by the Seoul Development Institute (currently The Seoul Institute) in 1993. In 1994, feasibility was tested in preliminary research on 6 companies located in Jongno-gu, and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure & Transport revised the Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act and officially announced the TDM system for companies. In May of the following year, the Seoul Metropolitan Council enacted the Seoul Ordinances on the Congestion Impact Fee Discount, Etc., and by August 1, 1995, the TDM policy for companies was launched. This policy targets buildings with a total area of 1,000 m² or more, providing varying discounts (2% - 30% by program) on the congestion impact fee based on participation and performance. If one company participates in multiple programs designed to reduce traffic volume, the discounts are added together. The traffic reduction programs that companies can choose include mandatory parking fees, voluntary road space rationing, and commuter buses and etc.

Table 2. Congestion Impact Fee Discounts by Traffic Volume Reduction Activity

| Activity | Target | Discount Rate (Unit : %) |

|

| Voluntary Road Space Rationing | 5th day No Driving | Facility Employees and Users | 20 |

| Odd-Even No Driving Day | 30 | ||

| Weekly No-Driving Day | 20 | ||

| Mandatory Parking Fees | Facility Employees and Users | 30 | |

| Parking threshold | Facility Owner | 20 | |

| 30 | |||

| 50 | |||

| Parking information provision system | Facility Owner | 10 | |

| Use of bicycle | Facility Employees | 20 | |

| Phased hours | Facility Employees(50 ppl and more) | 20 | |

| Operation of commuter bus | Facility Employees(100ppl and more) | 25 | |

| Operation of shuttle bus | Facility Employees and Users | 15 | |

| Call cab | Facility Employees | 20 | |

| Car-sharing | Facility Employees and Users | 10 | |

| Others | Facility Employees and Users | 10 | |

Source: SMG, Summary of the Seoul Ordinances on the Congestion Impact Fee Discount, Etc.

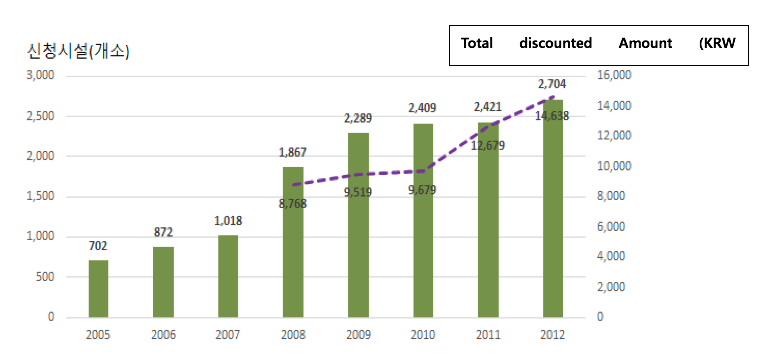

The TDM system for companies, introduced in 1995, offered highly attractive incentives, and the number of participating companies and the total discount amount have grown steadily. As of 2015, some 23.2% of the facilities subject to the ‘TDM program for companies’ are involved.

Figure 3. Companies Participating in the TDM Program (2013)

Source: Internal data, Seoul Metropolitan Government

The demand management programs for personal cars such as the Weekly No-Driving Day Program, and mandatory parking fees and programs to encourage the use of bicycle account for 70% of all programs. These programs are easier than others for companies to participate in, so the participation is high. On the other hand, phased commuting hours or restrictions on the use of personal cars by target facility employees may not be applicable due to specific business circumstances. Operation of commuter/shuttle buses and installation of parking guide system are costly, so the participation is low. Installation of facilities may have a short-term effect but not a lasting one required for overall traffic demand management.

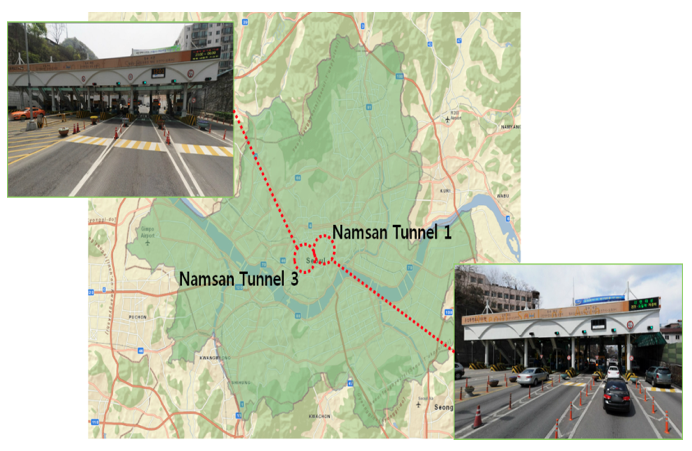

Congestion Charging at Namsan Tunnel 1 and 3

Singapore was the first city to implement the congestion charge followed by others like London, Rome, and Stockholm. Some States of the U.S. have run toll roads which applied the concept congestion impact fees to the congested segment of the expressways. In Seoul, discussions began in the late 1980s, but it was not introduced for circumstantial reasons. With the explosive growth in the demand for cars in the 1990s came a great need to contain the use of personal cars, so the congestion impact fee system has been implemented for Namsan Tunnel 1 and 3 since November 1996.

According to the Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act, a congestion charge is to be levied on road segments according to travel speed and average delay. Targets are arterial roads or adjacent zones under the influence of such roads where the average travel speed is less than 21 km/h (for 4 lanes or more, one way) or 15 km/h (for 3 lanes or fewer, one way) on weekdays only (excluding weekends and holidays) for 3 or more time periods per day. The charge may also be imposed on intersections or adjacent zones under the influence of such intersections where the average control delay time is 100 seconds or more (at signaled intersections) or 50 seconds or more (at unsignaled intersections) for 3 or more times a day. By this standard, most major roads in Seoul at the time when the charge was being discussed for introduction were subject to the congestion charge. Knowing that the sudden introduction of the charge in most or all of Seoul would likely meet severe opposition, the city aimed to phase in the system.

At Namsan Tunnel 1 and 3, the city began with a levy of KRW 2,000 for both directions from 7:00 – 21:00 Monday to Friday excluding Sundays and public holidays, based on the City of Seoul Ordinance (no charge on Saturday currently). The charge is levied against vehicles with only 1 or 2 occupants, while vehicles used by people with disabilities or for public purposes (ambulances etc.) are exempt.

According to studies by The Seoul Institute (2012), traffic volume on roads linked to Namsan Tunnel 1 and 3 dropped by 24.2% a month after the charge was implemented. Beyond that, the rate of decrease slowed; a year later (in November 1997), the decrease rate was 13.6%. Until August 1998, the daily average traffic volume was 77,000 vehicles, maintaining on average decrease rate of 14% . In the meantime, the volume of passenger cars at peak hours fell by 30% a year after introduction, with cars occupied by 1 or 2 people dropping substantially by 40.2%. Four roads near Namsan Tunnel 1 and 3 can be used as detours, and there had been concerns that the congestion charge would simply cause congestion in other areas as cars moved to the detour roads. According to a year-long study after the introduction, traffic volumes on the detour roads rose by only 5.7%. At the same time, average travel speed increased by 11.8%, from 24.5 km/h to 28.3 km/h.

Table 3. Collection of Congestion Impact Fees in Other Countries

| City | Purpose | Details | Effect |

| Singapore | -Relieve traffic congestion | -Introduced in June 1975 - Downtown around 07:30 ~ 19:00 |

-44% drop in traffic volume |

| London | -Relieve traffic congestion -Reduce air pollution |

-Introduced in Feb 2002 -Downtown (22 km²) around 07:00~18:00 |

-20% drop in congestion -83% rise in the number of bicycle users -16% drop of CO₂ |

| Stockholm | -Relieve traffic congestion -Reduce air pollution |

-Introduced in Aug 2008 | -22% drop in congestion -14% drop of CO₂ |

| Seoul | -Relieve traffic congestion | -Introduced in Nov1996 -Namsan 1&3 tunnel around 07:00~21:00 |

-16.8% drop in traffic volume |

Source: Mokwon University, Climate change, public transportation revitalization, and transportation demand management (2014)

One of the most important outcomes from the congestion impact charge was that cars with only 1 or 2 occupants stayed away from the tunnels and the occupants began resorting more to public transport such as buses or taxis. Studies by The Seoul Institute (2012) indicate that personal cars passing through Namsan Tunnel 1 and 3 dropped by 25.8% while buses increased by 4.7% in 2010 compared with those figures in 1996, the first year the congestion impact fee system was implemented. At peak commuting hours, the share of buses and taxis soared from 3.3% and 7.8% to 8.0% and 26.4% respectively.

Figure 4. Levying the Congestion Charge at Namsan Tunnel

Source: Street view, Naver.

Parking Lot Restrictions for Facilities in Certain Areas (Parking Threshold)

Before 1990, Seoul’s parking policy was keen on supplying more parking spaces to accommodate the increasing number of cars. However, such policies began to change with the growing importance of TDM in the 1990s. In line with the policy trend, Korea adopted a system of restricting the creation of parking lots (also called the parking threshold) for facilities in congested areas to curb the parking demand. Seoul set up its own parking threshold system and relevant bylaws for implementation to incorporate the unique circumstances of the city in restricting parking lots pursuant to the Parking Lot Act. With Seoul’s parking threshold regulations in place, parking lots for department stores and other commercial and business facilities in congested areas were limited to 50% of the parking lots located in non-congested areas.

Through the Parking Lot Act, the City of Seoul came up with parking threshold regulations via the City of Seoul Ordinance on the Installation & Management of Parking Lots. Seoul defines “Class 1 areas as defined in the public parking fee table” as “areas that are congested with automobile traffic”, as stipulated in the Parking Lot Act, The City of Seoul Ordinance also sets different standards for the installation of parking lots by the type of facility.

Seoul’s parking threshold program was first launched on January 15, 1997, was extensively revised on March 18, 2009 and remains effective to date. In the beginning, there were seven Class 1 target areas as defined in the public parking fee table, but this number grew to 10 due to the revised Ordinance in 2009. In the beginning, the target area was limited only to commercial areas but currently it’s been expanded to ‘commercial areas and quasi residential areas.’ With the parking threshold program in effect, the City of Seoul was somewhat successful with the TDM in reducing transportation demand.

Figure 5. Areas subject to Parking Threshold in Seoul

Source: The Seoul Institute (2014)

Policy Effects

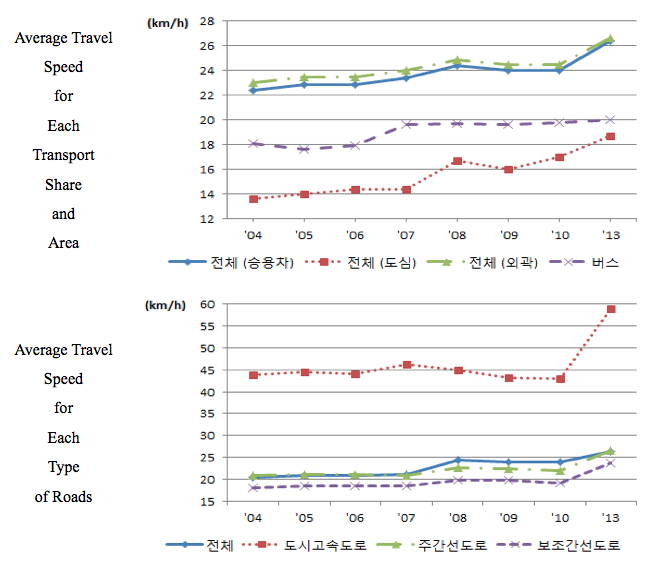

Travel Speed

Transport share of personal cars in Seoul has shown continuous drop since 1990s due to the TDM policy implemented in various ways while the share of public transport has steadily risen from 61% in 2004 to 66% in 2014. The average travel speed on major and downtown roads, in turn, has increased. In the early 2000s, the average travel speed in downtown Seoul was 22.4 km/h, rose to 26.4 km/h in 2013. A similar phenomenon has been observed in the outskirts of Seoul and on major arterial roads.

Figure 6. Changes in Average Travel Speed in Seoul

Source: Seoul Statistics

Air Quality

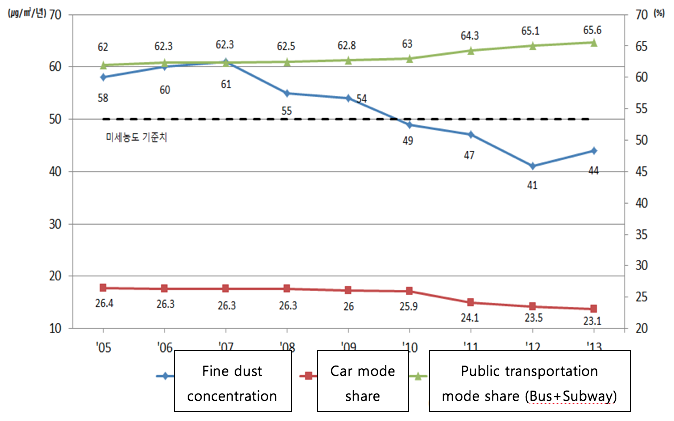

Seoul’s air quality has also improved thanks to the increased average travel speed, decreased transport share of personal cars, and increased share of public transport. The concentration of fine dust – a cause of respiratory diseases and a hotly debated social issue – was 60㎍/㎥ in 2004, higher than Seoul’s permissible level of 50㎍/㎥. However, the decrease in personal cars and other elements helped reduce the concentration each year, and by 2013 it had fallen to 44㎍/㎥.

Figure 7. Changes in Fine Dust Concentration and Transport Mode Share

Source: Seoul Statistics

Priority on Pedestrians in Urban Transportation Policy

As the TDM policy encouraged drivers to switch to public transport or walk, the city also began to shift its policy focus from cars to pedestrians. In line with this trend, Seoul created a “Walk-Friendly Seoul” by reducing the 4-lane Gwangjingyo Road to 2 lanes in 2007 and expanding the pedestrian walkway. In January 2014, the city created its first transit mall on Yonsei-ro. Many zones busy with pedestrians on weekends (e.g., Cheonggye Stream, Hongik University) were turned into pedestrian-only areas. The TDM policy has significantly helped Seoul become a more walk-friendly city.

Challenges and Solutions

A Need to Differentiate Coefficients

The congestion impact fee system has long attempted to differentiate the congestion coefficients by city size and facility to make them more realistic. However, the fees are unnecessarily levied on some areas where congestion is insignificant because the characteristics or specific conditions of the locations have not been taken into account. On the other hand, it has been suggested that the impact fee has little effect on heavily congested areas as the congestion impact charge is too low to bring about any differences. The congestion coefficients need to be differentiated in multiple steps and reflect the level of congestion as well as the unique characteristics of the region. For instance, upward adjustment of the congestion coefficient must remain within the 100% range of the coefficient set out in the Urban Traffic Readjustment Promotion Act; this needs to be revised so that upward adjustment can go beyond 100% for those facilities that significantly add to traffic congestion of an area. For those areas where public transit is inadequate, the coefficient should be lowered, even if the congestion increases due to certain facilities. At the moment, the differentiated congestion coefficients are actively promoted.

Enhancing Effectiveness of Congestion Impact Fee System

The congestion impact fee, adopted in 1990, is now over 20 years old and constitutes a major transportation policy in Seoul. However, questions have recently been raised about its effectiveness. The unit congestion impact fee has been recently adjusted in order to factor into the inflation rate as there has been criticism that practically the unit fee is too low to make difference as policy. The City of Seoul has revised the relevant ordinances in 2014 and has given the fees greater influence by applying pressure on companies that do not participate in the transportation demand management program and by providing attractive incentives to those that do.

Improvement of the Parking Threshold System

Currently, Seoul’s parking threshold is the same regardless of the intended use of the land, buildings, and surrounding areas. This one-size-fits-all program runs counter to the fundamental purpose of the system and is inefficient and illogical to some extent. Many large buildings allow parking outside or find parking spaces that get around the parking threshold. Opinions on the parking threshold vary greatly by facility type. For improved operational efficiency, the system needs more specifics in its design. The SMG has commissioned a research and service project to come up with ways to improve parking threshold system.

Improvement of the Congestion Charge Rate & Method at Namsan Tunnel 1 & 3

As part of the TDM policy designed to decrease the number of vehicles entering the city center and therefore mitigate congestion, the City of Seoul began to levy the congestion charge on 10-person vehicles and smaller if they carried only 1 or 2 people (including the driver) at Namsan Tunnel 1 and 3 from November 1996. However, the effect of the congestion charge in reducing traffic has gradually slowed, probably because the congestion impact fee is the same during peak and off-peak hours and has never been adjusted upward. Meanwhile, discount benefits had increased for compact cars and for the participants of Weekly No-Driving Day Program. Considering how overall prices and other transport costs have risen, the congestion impact charge should also be adjusted to a more suitable level and be differentiated by the time of day to have the desired effect on traffic volume.

References

- Mokwon University, 2014, Climate change, public transport revitalization, and transportation demand management.

- The Seoul Institute, 2007, Seoul’s transportation demand management policy to reduce the use of personal cars.

- Seoul Solution, 2015, Seoul’s Transportation Demand Management Policy, https://seoulsolution.kr/en

- The Seoul Institute, 2012, The effectiveness of road pricing policy in Seoul and its future development.

- Press Release (Seoul Metropolitan Government), 2013, “Seoul’s ‘broad reform’ in ‘transportation demand policy”

- The Seoul Institute, 2014, Study on Improvement of Limitation of Parking Space Policy.

- Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2014, A study on sustainable urban transportation management

- Seoul Metropolitan Government Ordinance, The Standards & Reduction Rate for the Traffic Reduction Program

- Seoul Metropolitan Government Ordinance on the Congestion Impact Fee Discount Rate