Proyecto de Restauración del Arroyo Cheonggyecheon.

Issues and Paradigm Shift

Decline in the downtown of Seoul

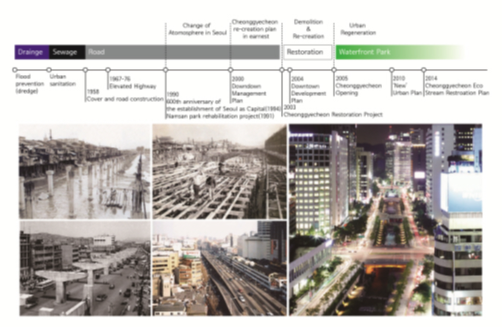

The downtown of Seoul, including the area around the stream of Cheonggyecheon, was the center of urban economy filled with many businesses. The road covering Cheonggyecheon and the elevated highway were the artery of urban transportation. The downtown was truly a place that led the urban economic development by generating new jobs and spurring creative activities and innovations. From the 1980s, however, Seoul’s economic structure changed from small-scale light industries to manufacturing and services. The downtown was composed of too small plots and narrow roads to accommodate the new industries. Development was not easy because of the land prices that were already too high. As development and redevelopment stagnated, the old downtown became increasingly obsolete. As the land prices didn't fall whatsoever while the landscape was worn out and the quality of life deteriorated, people and businesses left the downtown area. The urban structure also changed. In the past, the downtown had been the center of everything―residence, work, production, etc.―, but it became a central business district that focused more on production and businesses in the course of urbanization. Residential area moved to the suburban area since it was more comfortable, quiet, clean and appropriate to educate children. Seoul's urban structure kept changing through multi-centralization with growing sub-centers and competition among different land uses. As the old downtown failed to adapt to the change, people and businesses began to turn away from it.In 2000, the number of businesses within the downtown was 77,000, down 24.1% from 100,200 in 1991. Given that the number of businesses in the entire Seoul jumped by 24.6% during the same period, the 24.1% decline was enormous. The share of downtown businesses in the overall number of businesses in Seoul also declined to 10.8% in 2000, from 17.7% in 1991. The number of downtown workers in 2000 marked 400,000, 54.3% decline since 1991. Their share in the overall Seoul also fell from 18.9% in 1991 to 11.7% in 2000.

Safety issue of the elevated highway

It was the safety issue that triggered discussions on the restoration of Cheonggyecheon. The structure of covering road and the elevated highway was deteriorated, causing serious safety risk since the 1990s. As an in-depth investigation conducted by the Korean Society of Civil Engineers in 1991-92 found the corrosion of the steel frame inside the highway and structural flaws in its upper plate, a thorough repair work was conducted for a 2-kilometer sector of it. The 30-year-old road covering Cheonggyecheon costed substantial amount of money for continuing maintenance and repair. Another in-depth safety checkup conducted from August 2000 to May 2001 revealed that cracks and exfoliation persisted in the upper slab, while the load carrying capacity was insufficient due to the worn-out concrete beams. As a result, a full-scale reconstruction was inevitable. Reconstruction was estimated to cost 93 billion won in three years. In 2001, the city government of Seoul planned to demolish the elevated highway and reconstruct it, beginning from August 2002.

Shift from maintaining the elevated highway to restoring the stream

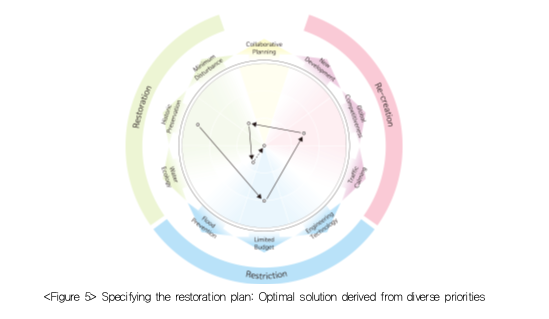

Since the 1960s, development, construction, production and efficiency have always been priorities in Seoul. Starting from 1990s, however, the urban planning paradigm shifted to focus more on human, history, nature and environment, as the people's consciousness changed over the course of socio-economic development.Discussions on justification, necessity and significance of restoring Cheonggyechon became lively since the late 1990s. The restoration became a major topic during the mayoral election campaign in the first half of 2002. Over the course of political debate, the direction of initial plan shifted from reconstruction of the elevated highway to restoration of the stream. There were still many choices and decisions to make between the idealistic goals―historical values, eco-friendliness, optimization in each sector, etc.―and the practical considerations―cost, time, optimization in the entirety, minimization of inconvenience among the neighboring businesses, phased approach, etc.

Regeneration of Cheonggyecheon

Framework of urban revitalization by restoration of Cheonggyecheon

Public-driven Cheonggyecheon restoration + Private-driven urban revitalization

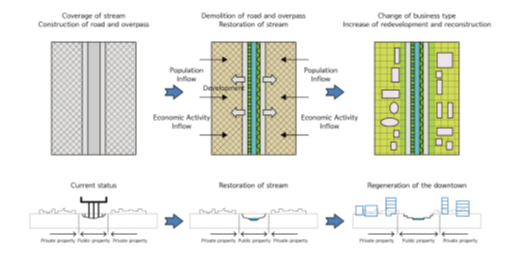

The aim of the project was to restore a decrepit public space to create a waterfront in the downtown, improve the environment and restore the historical value. Such an attempt would revitalize the city by attracting more population and more business activities, which would eventually enhance growth momentum and attract more private investment. At the same time, the discussions included the measure through which the private and public sectors could share the benefit, while achieving urban revitalization led by the private sector. Along with setting the long-term goal, determining specific project boundary was another challenge. While Cheonggyecheon itself was a public place, the surrounding area was privately held properties. To include the private properties in the project would not only cause the project budget to snowball, but cost enormous time to deal with administrative matters such as revision of urban plans and compensation. Therefore, the Seoul municipality decided that the restoration work itself would exclusively cover the public land within Cheonggyero to ensure the feasibility of the project. In this approach, the public and private sectors had to take their respective role in turn. Firstly, the city government was to demolish the coverage and the elevated highway, create an eco-friendly waterfront and restore the historical value of the stream through public investment. The ripple effect of restoration would help revitalization of the downtown and the neighboring area, which will be conducted in partnership with the private sector in a way that both public and private sectors could benefit.

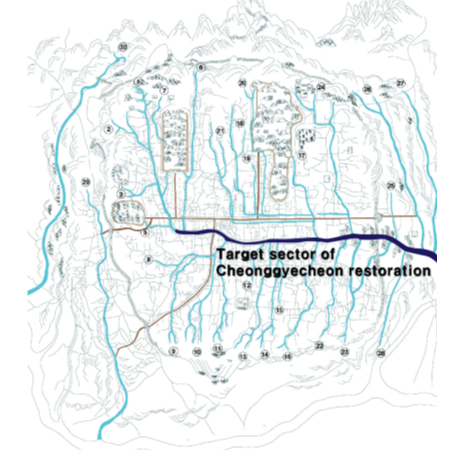

Restoring Cheonggyecheon, restoring natural values of aquatic ecosystem of Seoul

Cheonggyecheon is a long stream that flows across the downtown. It also has many tributaries. By restoring its tributaries such as Junghakcheon and Baekundongcheon in the upstream, the city had a long term plan to rehabilitate the aquatic ecosystem of Seoul. But this could not be implemented at once. Therefore, the project boundary was designated between Sejongno and the stream's confluence point with Jungnangcheon.

Controversies in the course of specific plan development

Although people agreed on the necessity of Cheonggyecheon restoration, they had different opinions about what the restored stream should look alike. Some prioritized the historical values while others wanted to minimize the contruction-related inconvenience in the vicinity. Transportation and flood prevention were also big issues to consider, as were the practical issues such as construction period and cost. In addition, further decision had to be made on the budget, phasing of implementation, project boundary, water supply and technical level of construction. There were a great deal of conflicts in the planning stage due to contradictions among many different factors to consider. The city therefore organized the citizens' commission to collect diverse opinions of citizens, experts and stakeholders, and reflected them in the master plan. Given that it was a long-term project in nature, it was important to set a long-term direction. However, the city needed to conclude an optimal solution at that specific point to move forward. After a series of discussions, the Cheonggyecheon restoration master plan was completed in June 2003. Even after that, discussion to fine-tune the project and develop a longer-term initiative continued.

Major components of Cheonggyecheon restoration plan

The restoration had to consider diverse factors of Cheonggyecheon in the historical, structural and functional aspects. Restoration of historical remains such as old bridges and stoneworks at the stream was one of the main concerns by citizens. The restored stream also needed to have enough capacity to deal with floods, as abnormal rain fall became more frequent due to climate change. In addition, it was necessary to maintain its previous role for transportation and sewage. Most of all, the project had to create a better natural environment, which was the biggest aspiration of the citizens. To this end, it was imperative to secure water supply for the stream, which turned out a difficult task.

■ Restoration of historical values

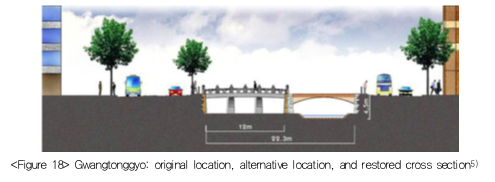

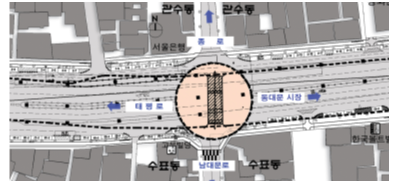

Restoration of historical values was important in justifying the project and ensuring citizens' support. With this recognition, the Seoul municipality set it a principle to preserve all the heritage excavated during the construction. In the actual work, however, the safety of citizens emerged as a bigger priority. The municipality's principle was to restore the originality to the extent in which citizens' safety from flood and other risks is ensured. However, some members of the citizens' committee and some civil associations insisted that the stream be restored entirely in its originality. Such a difference sharpened in the phase of actual work. As specific concerns emerged with regard to flood control, transportation and negotiations with the neighbor businesses, some of them became incompatible with the preservation of historical remains.One of the biggest issues was the restoration of Gwangtonggyo bridge. There was a strong argument to restore it to its original shape, which required an extensive work. In order to secure enough cross-sectional area for the water flow, in other words discharge area, it was necessary to purchase private lands in the bridge's vicinity, but it was practically impossible. Insufficient area for discharge would lead to failure in safety and flood control. The city finally decided to rebuild Gwangtonggyo at a spot 150m away from the original location to the upstream, in a belief that restoration at the original location will be possible in the future when a better condition is prepared.

<Table 5> Comparison of arguments about restoration of Gwangtonggyo

|

Current status |

Restoration in its originality |

Alternative |

|---|---|---|

|

|

※ Restoration in the original shape and location would be possible in a better condition in the future |

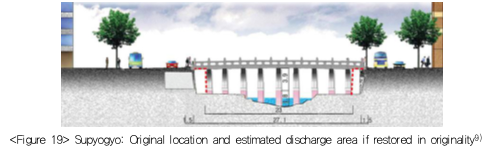

Restoration of Supyogyo in its originality might incur similar problems. The Cultural Heritage Committee of Seoul concluded to leave Supyogyo where it was, in the Jangchungdan Park, in order to avoid deterioration of the original stones. At 27.5m, the original Supyogyo was longer than the width of the restored stream (22m) at the point. To restore it in the original shape, the city had to expropriate private properties in the vicinity, which would inevitably prolong the construction and cause more inconvenience for the neighboring businesses. Therefore, the municipality decided to restore Supyogyo in the future, once favorable conditions are made available.

■ Flood prevention and safety measures

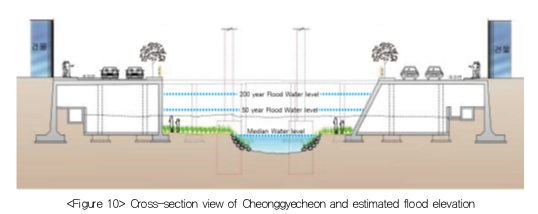

Although the restoration of Cheonggyecheon was initiated in a bid to restore historical and environmental values, the safety issues including flood prevention came to the fore in the course materialization. The city set the target flood recurrence interval of 200 years. Given that other 2nd-grade local streams were managed based on 50-year interval assumption, it was a decision to better ensure the citizens' safety by securing sufficient stream capacity to deal with local torrential rainfalls. The city also strived to secure discharge area by excavating the underneath of both banks.

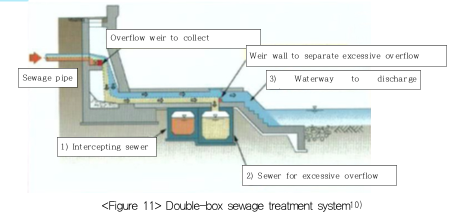

■ Sewerage treatment

Substantial number of sewerage pipes were buried near Cheonggyecheon, since sewage water of the downtown Seoul was traditionally gathered along it. Finding ways to treat such sewage was a precondition to the restoration. Since the existing sewerage system was often combined with rainwater collection system before it reached the stream, it was practically impossible to segregate sewage from rainwater. Separation between them was also inappropriate because the downtown rainwater flowing into Cheonggyecheon was highly polluted. Therefore, the municipality adopted a double-box system. The sewage would be treated in a combined system, but highly-polluted initial rainfall would be segregated into a separate pipeline to be treated at the treatment facilities, not flowing into the stream.

■ Water supply and its quality

Cheonggyecheon was historically a ephemeral stream. It was difficult to draw water from the vicinity, because underground water level became lower due to urbanization. Given that there was no valley water from the upstream, artificial supply of water was inevitable to maintain the stream. The Hangang (Han River) and the groundwater discharged from nearby subway stations were selected as water sources. The Korea Water Resources Corporation attempted to tax the Seoul municipality for drawing water from Hangang, but it was eventually discounted by 100% on the ground that the water would be used for the public interest. As for the water quality, the water treatment was decided as secondary treatment considering relevant conditions and costs.

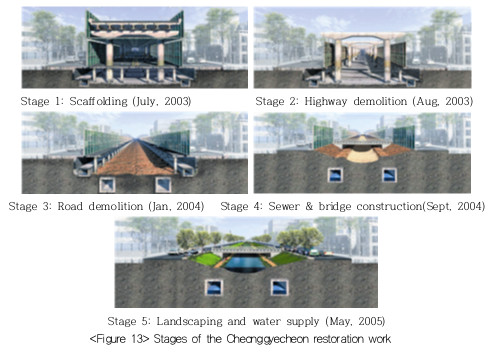

Overcoming technical difficulties - Short construction period, limited budget, and waste recycling

As announced in 2001, Cheonggyecheon was planned to be demolished and renovated in three years from 2002, during which inconvenience of neighboring merchants was inevitable. Since the main complaint of neighboring merchants was to minimize construction period, it became a priority to complete the work as soon as possible. In order to shorten the construction period and accommodate a diversity of creative ideas from the private sector, the contract for the project was processed in the "fast-track design-build" system. Among the companies participated in the bidding process, based on the basic design guidelines developed by the city government of Seoul, contractors were selected. Since three different entities designed each zone separately, the city government intervened to ensure consistency and solve the problems such as concept differences or errors in sewage pipeline's connectivity between each zone. The construction started in July 2003, and major structures were demolished by October. During demolition, the detailed design for construction works in the stream was developed simultaneously, and the construction was completed in the early 2005. After a series of test-run during the rainy season, the project was completed by September 2005, taking 27 months in total. 96% of waste generated during the construction was recycled.

Revitalization of the downtown area

In order to revitalize the downtown area, utilizing the development potential which increased through the Cheonggyecheon restoration, the existing urban plans needed some modification. In this context, the "Downtown Management Plan" devised in 2000 was revised and renamed into a "Downtown Development Plan," adopting more active nuance by changing the word.

Downtown revitalization plan

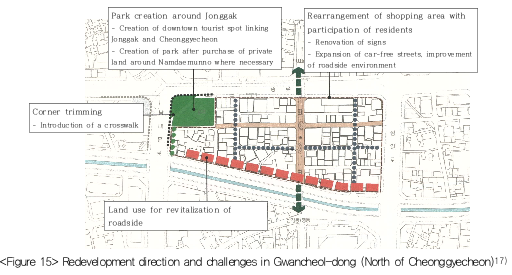

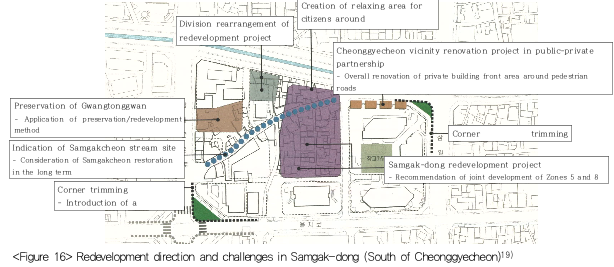

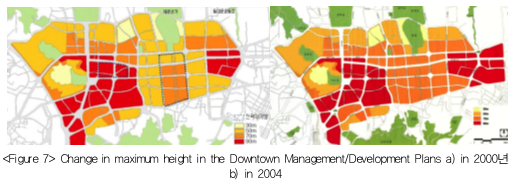

Along with the restoration efforts, the Seoul municipality set it a goal to refrain from excessive development and create places for cultural experience, businesses, shopping and tourist activities around Cheonggyecheon, with an aim to maintain economic vitality of the area. It created tourist programs to allow participants to look around historical and cultural heritage around Cheonggyecheon and developed an urban management plan to regulate building height, building coverage ratio, development density and parking standards. The Downtown Development Plan in 2004 divided the area around Cheonggyecheon into 22 blocks and categorized them into special feature preservation zone, redevelopment zone, voluntary renewal zone and comprehensive reorganization zone in accordance with their characteristics, land use pattern and historical features. Among them, the redevelopment zones and comprehensive improvement zones were intended to be developed actively to strengthen their characteristics. On the other hand, preservation and voluntary renewal zones were to preserve their identities, while adapting to the circumstantial changes.

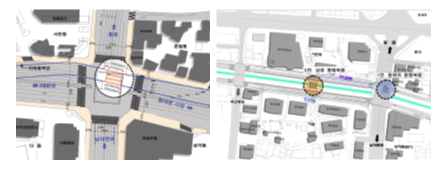

For example, in Gwancheol-dong, designated as a preservation zone, large-scale development was limited by imposing maximum plot area for co-development to protect its spatial identity, while commercial usage for street revitalization in the lower stories of buildings was encouraged to create a pedestrian-oriented environment. (See figure 12)

In Samgak-dong, designated as a redevelopment zone, a group of small buildings were merged and redeveloped into a large building to provide public space for the citizens along the stream. However, historical buildings and the traces of Cheonggyecheon tributary were preserved.

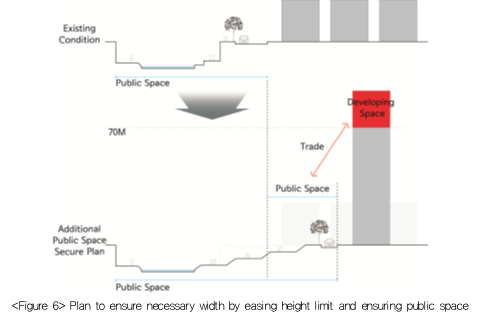

Ensuring public goods in the vicinity

In the aspect of revitalization, the biggest problem of land use pattern around Cheonggyecheon was an absolute lack of green space and public space for the citizens to walk around and rest, other than Cheonggyecheon road. The elevation difference between the ground level and the stream were considerable because of the flood control. Also, the stream was too narrow to create a gradual slope to connect it to the ground level. Moreover, bigger width needed to be secured to make Cheonggyecheon a more naturally-looking curved stream in the longer term. To ensure sufficient width, the city had to buy the land from the owners of private properties in the vicinity, but purchasing neighboring properties would be an extremely time- and money-consuming process. Another way to prevent losses in the private sector and ensure public space was to secure public land through negotiation. When the private owners hand over a part of the land for public usage, the public gave them incentives to allow the building developed higher. Physically speaking, the municipality horizontally secured public space while allowing more developments vertically.

Easing the height regulations might undermine the effort to control the downtown skyline, but it was a practical way for the city to secure public space by compensating the private sector's losses. Purchase was practically almost impossible due to enormous financial burden, prolonged administrative processes and complicated interests of many small plot owners. In such a context, the height regulation in the vicinity of Cheonggyecheon was eased. Looking at height regulation of the downtown plan, many 50 meter limit zones in the 2000 plan became the 70 meter zones in the 2004 plan.

Achievements

Improvement of environment: Creation of wind corridor, reduction of heat island effect, better air quality, and restoration of natural environment

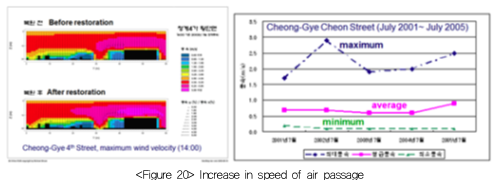

Physical change and reduced traffic volume in the Cheonggyecheon area reportedly reduced the concentration of fine dust (PM-10), NO2, volatile organic compound (VOC) and other air pollutant in a significant level, shorty after the restoration. The heat island effect in the downtown also declined. The temperature of the Cheonggyecheon area before the restoration was 2.2℃ higher than the average of Seoul, but it declined to 1.3℃ after the restoration, dropping by 8 to 18%. The temperature of green point within the stream was 0.9℃ lower than neighboring area, As air-blocking elevated highway disappeared, wind corridor was established and the creation of stream affected neighboring environment. Ecosystem was also restored as wildlife fish species, birds, insects and plants increased.

|

|

2003 |

2004 |

2005-2006 |

2010 |

2011-2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Plant |

121 |

136 |

160 |

510 |

365 |

|

Wildlife animals |

9 |

18 |

19 |

37 |

48 |

|

Insects |

70 |

94 |

113 |

248 |

112 |

|

Fish |

7 |

7 |

21 |

25 |

23 |

|

Benthic invertebrate |

28 |

28 |

27 |

29 |

44 |

|

Source |

Ministry of Science and Technology (2007) |

Seoul Metropolitan Facilities Management Corporation (2010) |

Seoul Metropolitan Government (2012) |

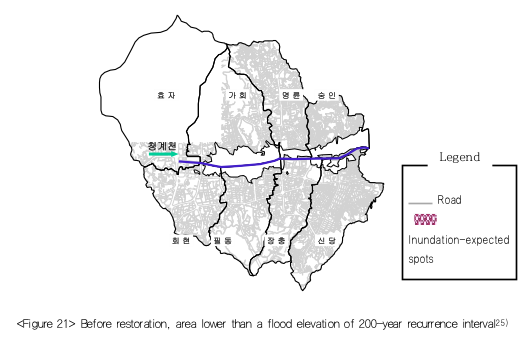

Flood control

Cheonggyecheon is the lowest-lying area in the old downtown with an extensive basin to collect rainwater and gently sloped banks, which make it a highly flooding-prone stream. Overflow occurred for two consecutive years before the restoration began, causing damage in the downtown area. Given that local torrential rainfall is frequent in Seoul, discharge area of the restored stream was designed on the basis of 200-year recurrence interval. While the estimation at 200-year recurrence interval had revealed that most of the low-lying area around Cheonggyecheon had been subject to inundation before the restoration, there was no report of flooding due to lack of discharge area after the restoration, which means that the vicinity was made free from flooding damage.

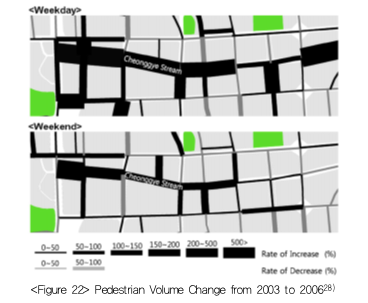

Increased public space, pedestrian-friendly environment, more floating population and tourists

The floating population in the Cheonggyecheon area of weekdays and weekend recorded a significant increase. The increase was larger in weekdays than in weekends, meaning that citizens visit the stream often in their daily lives. In the 2013 survey, 89% of respondents were on the fence or satisfied with the walking trail along the stream. They were particularly satisfied with the uniqueness of the place itself. However, they showed lower level of satisfaction in accessibility, because the access from the ground level to the stream was limited due to the stream's narrow width. From the perspective of citizens, the biggest contribution of the restoration was the creation of a place to relax. In the 2013 survey, 59.6% of respondents indicated so. Cheonggyecheon also became a venue for diverse cultural events: 259 events were hosted in 2005-07, firmly positioning the stream as a place for culture and recreation.

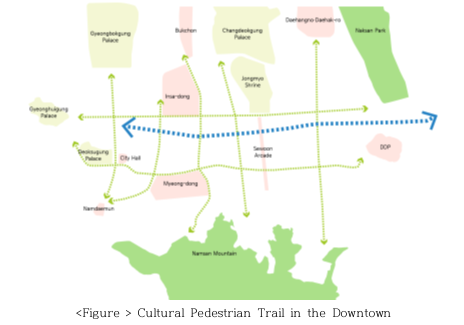

With the restoration of Cheonggyecheon, other attractions in the downtown―Gyeongbokgung, Changdeokgung and Myeongdong―were linked through pedestrian roads, enhancing the overall value of the public spaces in the downtown. The downtown of Seoul thus became a more attractive tourist spot. Almost all tour guide books on Seoul include Cheonggyecheon in the recommended itinerary.

Downtown revitalization, increasing economic activities, and rise of real estate prices

The restored stream enhanced the development potential of the vicinity and accelerated the downtown redevelopment. In the upstream near CBD, the changes in the land use stagnated during the restoration period, but skyrocketed since 2006 after the restoration was finished. 74.4% of land use changes were for commerce or office purposes, which shows that development for such purposes increased in the CBD area. In particular, many large-scale building were developed after the restoration.

Changes in citizens' consciousness

One of the big achievement of the Cheonggyecheon restoration was the citizens' awareness on the value of natural environment. Even before the restoration project, people already had interests in natural environment and aspiration for a better Cheonggyecheon. After witnessing the restored stream and its environment, people's recognition on the value further increased. According to a survey on citizens' willingness to pay for a natural stream before and after the restoration project, the annual economic value of a natural stream appreciated by the citizens jumped from KRW 20,226 to 37,724 per household. The survey confirmed that the citizens of Seoul placed a higher value on the natural environment after experiencing the restored Cheonggyecheon.

Implementation system and finance

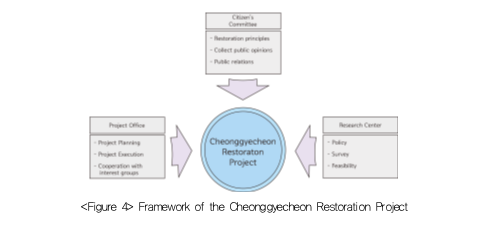

Triangular implementation system

The Cheonggyecheon restoration project differs from the past practices in that it created a triangular implementation system, composed of the citizens' committee, the headquarter and the research group. Such a framework was advantageous in efficient project implementation, collection of public opinion, and building public relations.

An official channel to collect various opinions of citizens was necessary to push forward the project efficiently. The Cheonggyecheon Citizens' Committee was established for that purposes. Experts of the Cheonggyecheon Revival Research Group joined the committee, along with other experts and citizen representatives of various backgrounds. The committee's primary role was to set the directions of the restoration project. It was given rights to audit and monitor as well as to simply advise on the project. The committee also had legally-binding rights by enacting ordinances. In addition to deliberation and assessment, the committee conducted a series of hearings and briefings to garner various public opinions, build a public consensus and encourage citizens to participate in the project.

The headquarter office that actually implement the project was also necessary. It launched in July 2nd, 2002, and initially consisted of three departments: each on to manage, plan and implement the project. The organization was modified continually to adapt to the evolving stage of the work. Focusing strictly on the actual works on the site, the headquarter was established in the City Hall to ensure efficient communication and project implementation. It conducted a weekly meeting hosted by the mayor every Saturday to maximize the efficiency. All the highest-responsible persons attended the meeting to discuss the major issues of the project and made decisions in a speedy and determined manner. The Saturday meeting thus contributed to resolving potential conflicts within the municipality and ensuring consistency of the work.

Cheonggyecheon Research Group was established temporarily under the Seoul Development Institute (renamed afterwards as Seoul Institute) to support the restoration project. Its assignment was to conduct research projects on the basic data and blueprint for the Cheonggyecheon restoration. It contributed to the project by researching on most of issues related to the restoration, such as transportation, land use, urban planning, environment and culture. It also organized a variety of seminars and meetings with outside experts for advices, and conducted a variety of activities to promote the restoration through academic events, public relations, and addressing media outlets.

Financing

Budget estimation and its financing were important issues in the project. As the city aimed to have the project recognized as a public one and secure the government budget, it was important to get the approval from the Seoul Metropolitan Council. To secure the budget of KRW 384 billion for the restoration, the municipality utilized KRW 100 billion that was initially assigned for the overall renovation of Cheonggye elevated highway. It also saved some KRW 100.4 billion by downsizing less urgent projects and introducing creative work procedures to enhance efficiency of the city administration. The rest of the budget was secured from the city's general accounting. Further, donations were made on some bridge. The project fund for Samilgyo, Mojeongyo, Gwangtonggyo and Jangtonggyo was donated, allowing the municipality to save KRW 8.2 from the budget. In total, KRW 384.4 was invested in the project. The amount was merely about 1% of the total budget of the Seoul municipality, which was not burdensome at all. Compared to other waterway restoration projects in Korea and abroad, the Cheonggyecheon restoration project was highly economical.

|

Project Dimension |

Project |

Time |

Scale |

Cost |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Project DimensionProjectTimeScaleTotal |

Cost/length |

||||

|

Cheonggyecheon |

2003-2005 |

5.84km |

$ 376.9 mil (384.4 bil) |

$ 64.5 mil/km |

|

|

Linear Urban Infrastructure |

The High Line (Section 1,2) |

2003- |

1.6km |

$ 152 mil |

$ 95.0 mil/km |

|

Linear Urban InfrastructureThe Big Dig |

1982-2007 |

12km |

$ 22 bil |

$ 1,833.3 mil/km |

|

|

Linear Urban InfrastructurePromenade Plantéee |

1987-2000 |

4.5km |

$ 25 mil |

$ 5.6 mil/km |

|

|

Urban Waterways |

Isar Plan |

2000- |

8km |

$ 34 mil (Euro 28 mil) |

$ 4.3 mil/km |

|

Urban WaterwaysSan Antonio Riverwalk Downtown Reach |

1999-2002 |

app. 1km |

$ 13.3 mil |

$ 13.3 mil/km |

|

|

Urban WaterwaysSanjicheon |

1997-2002 |

474m |

$ 35.8 mil (W 36.5 bil) |

$ 75.5 mil/km |

Challenges to overcome

Opposition from neighboring merchants and street vendors

The strongest opponents to the restoration of Cheonggyecheon were the merchants in the vicinity of the elevated highway. They worried about traffic congestion and negative effects such as noise, dust and other inconvenience during the demolition and construction. The solidarity among over 200,000 merchants was strong as most of them had been there for more than 20 years. They were mostly in a wait-and-see attitude at the initial stage of the project. As the project launched in earnest, however, they started to organize protest groups and held demonstrations. From February to September in 2003, the conflict intensified between the municipality and the merchants, which was sometimes led to violence.

Some 4,200 meetings in various forms were held for negotiations between the city officials and the merchants. The city's strategy was to keep the principle of no direct compensation. The municipality promised to complete the construction work as soon as possible, establish parking lots at the Dongdaemun Stadium and provide free shuttles during the work to minimize the merchants' inconvenience. It also provided financial and administrative support for businesses that wanted to move away and gave them favorable rights to move into a new commercial complex to be created in Munjeongdong area if they wanted. The city also had the street vendors move to the folk market in the Dongdaemun Stadium, and then to a folk market in Sinseol-dong after the stadium was demolished for redevelopment.

Concerns over the traffic chaos

Traffic congestion was one of the primary concerns since the very first stage of the project. Many concerned that eliminating 18 lanes by demolishing the elevated highway and the coverage would generate serious traffic inconveniences. The city government created circular-route buses, increased parking fee to discourage traffic, cracked down on illegal parking, and introduced reversible and one-way lanes to address such concerns. However, these could not be the fundamental solutions to the downtown transportation. The city accelerated its efforts on the transportation reform to change Seoul's transportation to mass-transit-oriented system by increasing capacity of buses and subways. The restoration of Cheonggyecheon triggered the transition to public transit oriented transportation system. The share of private cars in the total downtown traffic volume decreased from 21% before the restoration to 15% in 2007, while the share of public transport, walking and bike-riding increased.

Flooding and technical issues

Technical issues were also important. In order to shorten the construction period to minimize the inconvenience of the merchants, cutting-edge technologies were adopted to speed up the work. To prevent damage in businesses and maintain traffic on the roads along the stream, the construction had to be conducted inside the stream. Therefore, cutting-edge technologies such as diamond wheel saw were adopted to accelerate the work. Severed materials were loaded on trucks and moved to the outskirt of the city where they were shredded and recycled. An important mission in the construction process was to complete important foundation works between rainy seasons. As Cheonggyecheon had a large basin area, construction tools and materials in the stream were vulnerable to flooding damages. Such an accident actually happened in 2004 and the project was on the verge of serious damage. The construction works had to be completed as shortly as possible, in preparation of floods that came every summer.

Discordance spatial patterns of urban revitalization

When it comes to the redevelopment of the stream's vicinity, controversy have persisted over whether the small plots and lower buildings have to be prioritzed for preservation of the small alleys and the historical values of the downtown, or the larger plots and higher buildings have to be prioritized to provide a public space. As seen in the changing height regulations, the directions to define the identity and usage of the downtown has continued to change. It was therefore important to balance between preservation of the memories of the past and the accommodation of people's new aspiration in the land use. To this end, a detailed redevelopment strategy was necessary to adapt to distinctive land use patterns and identities of each block.

Lessons Learned

Creative destruction of public space

public space is an important asset in the city. Securing and utilizing it determines the quality and competitiveness of the city. The primary function of Cheonggyecheon in the downtown Seoul has changed over time. During the Joseon dynasty, the main role of Cheonggyecheon in the city of 100,000 population was "drainage" and flood prevention, while the function of "sewage" became important as population grew since the 20th century. After the Korean War, the population of Seoul skyrocketed and an open sewer like Cheonggyecheon became inappropriate due to diseases and odor, while roads became necessary in the process of industrialization. Accordingly, Cheonggyecheon was covered with roads since 1958 and an elevated highway was constructed. Since then until the 2000s, the main function of Cheonggyecheon was 'road,' Today, it is important to create a natural ecological park where people can breathe and relax in the downtown and walk around. As such, the main role of Cheonggyecheon has evolved. However, such a creative destruction of public space to create it anew requires thinking out of the box. Also, new technologies and dedication are essential to make the new ideas into a reality. A public space is not a fixed one. it can evolve.

■ Creative envisioning

"Envisioning" is the most important keyword in the restoration of Cheonggyecheon. Eliminating 18 busiest lanes at the heart of Seoul was certainly something beyond imagination, given that cars were continually increasing and traffic jams were intensifying. Many people concerned the traffic chaos and strongly opposed the plan. However, the elimination of roads and the creation of a waterfront made the downtown more environmentally pleasant and vibrant. The quality of lives of the people improved, and their awareness on public space also changed. Contrary to the prediction of many experts, the transportation system moved quickly to public transit-oriented, which improved the downtown traffic condition.

■ Leadership

Leadership is crucial in such a ground-breaking transition. A leader should be able to present a clear vision, run the organization and its human resources in an efficient way, resolve the internal skepticism and external conflicts, and communicate and persuade people. Such a leadership actually facilitated the renewal of urban space. In particular, the role of a leader was crucial in leading the organization of public officials effectively, preventing potential cacophonies through constant discussions, altering the organization to focus on the work at the site to ensure efficiency, and persuading different stakeholders to build the consensus.

■ Appropriate implementation system and efficient project management

At the initial stage of the project, the citizens' committee composed of the general public and experts contributed a lot to setting the project's direction by gathering different opinions and building consensus. The restoration could not be achieved with partial approaches. Coordination between different sectors of work―water, road, sewerage, civil engineering, gardening, architecture, urban planning, economics, social affairs and welfare―was crucial to move forward. It was thus appropriate that the municipality appointed a vice-mayor level official to take a responsibility for organizing and coordinating the project effectively. Also, the weekly meeting held at 8am every Saturday played a key role in speedy decision-making and resolution of conflicts between different city departments. As a result, the project could be successfully completed within the target deadline, without exceeding the budget by a large margin.

■ Public-Private partnership, and the triangular implementation system

It is also noteworthy that a close public-private partnership contributed to the downtown transformation. To this end, the triangular implementation system consisting of the administrative agency to implement the project, a research body to provide expertise and a citizens' committee to gather citizens' opinions worked effectively. Such a practice paved the way for the emergence of collaborative planning in the urban planning of Seoul.

■ Pros and cons of politicalization

Politicalization of the Cheonggyecheon restoration was a double-edged sword. While the political momentum certainly drove the restoration project more powerfully, the project became a subject of political controversy, rather than a factor of urban revitalization. It also became a matter of political strife in the mayoral election every four years. Despite the necessity of long-term management, the public sector could not fully ensure the consistency in managing the Cheonggyecheon restoration and urban revitalization efforts. It is unfortunate that the task of urban revitalization exclusively fell to private sector, due to the absence of public intervention.

Rebirth of Cheonggyecheon: A new step forward to the future of Seoul

The first chapter of the Cheonggyecheon restoration finished in 2005. Although some people argue that the project was conducted in an extreme haste, it is remarkable that the project identified practical scope of work in the complicated downtown area and completed it in a short span of time and in an efficient manner that minimized inconvenience. Before the restoration, Cheonggyecheon was a place of deterioration and pollution. There were vague aspirations for change, without specific action plans. Since it had been used as a motorway for 50 years, people perceived Cheonggyecheon as a place for cars. Envisioning a place of nature and waterway in such a condition and realizing it required literally 'thinking-out-of-box' approach. By replacing cars and artificial structures with the nature, creating a human-oriented landscape in the city and equipping the area with historical values and identity, the Cheonggyecheon restoration project became a turning point in shaping the city of Seoul. It also triggered a remarkable shift in citizens' consciousness. When it comes to the controversial issue of the extent to which historical remains be restored, it was appropriate that the municipality took the phased approach rather than restoring everything at once, since that requires excessive social costs in the complicated situation of downtown. However, it is regrettable that the city failed to build enough social consensus on that front. The new Cheonggyecheon was not simply a restoration, but a re-creation. It was basically about demolishing the coverage and elevated highway and creating a pedestrian-oriented and eco-friendly stream. The project also included building infrastructure for sewage treatment and flood prevention. If the Seoul of the past, with some hundreds of thousand people, relied on the self-purification capacity of the stream, the restoration project changed Cheonggyecheon to an eco-friendly, human-friendly public space in the downtown with the historical values and potentials for future growth. Triggered by the re-creation of such a public space, the revitalization of the urban area is still going on today.