Sistema de cobro por la recogida de residuos basado en el volumen (VBMF, por sus siglas en inglés) para Residuos Sólidos Municipales

Background

How to Implement the Pay as you throw system

To discharge food waste, you should buy and use the standard waste bags or use the chip or RFID based system. In the case of large sized waste, you have to buy stickers from the relevant autonomous districts and attached them to the waste before discarding them, or you can hand such wastes over to specialized waste collection agents. (Ministry of Environment, Nov. 2012; Resource Recirculation Bureau, Ministry of Environment, Nov. 2012) The items that can be recycled to create resources or have value of resources like paper, scrap metal, large home appliances, small home appliances, fluorescent lamps, batteries, cooking oil, etc. should be separated and discarded according to the methods regulated by the government. (Minister of Environment, 2011)

In the case of the general waste and food waste, the discarders bear the whole or a part of expenses for waste collection and treatment and the cost depends on the amount of the discarded waste. That is why the waste fee in Seoul is called pay as you throw system. The measuring method for general waste and food waste is different. The measuring method for general waste is the standard bags which are made according to the quality standards<2> set by the government. The waste discarders can buy the bags in desired sizes at designated stores (such as convenience stores, laundries, etc.).

The expenses for waste collection, treatment and production of bags and the commission for the stores are included in the price of the bags, granting the nature of marketable securities to the bags.

The measuring method for food waste are either an RFID based waste weighing system, chips (or stickers) or standard waste bags, more various than the method for general waste. RFID based waste weighting system is used to measure the weight of waste and impose consequential fees. An advantageous trait of this system is accurate weighing of the discarded waste. But the devices have disadvantages at the same time, because the system has a complicated configuration consisting of weighing devices, discarder recognition system and storing devices to save the discarders and results of weight measurement. Chips or stickers are used with the standard containers. Daily volume measuring and monthly volume measuring are all available with this solution.

Except for recycling products, large sized waste and used coal briquettes that are allowed to be discarded using other routes, all wastes discarded in Seoul must be made according to the volume-rate disposal system without exception and the corresponding fees must be paid. If you do not pay the fees when you discard your waste, it is a violation of the waste management law or ordinances of the local government, and is subject to the penalties of those laws or ordinances.

<Table 1> Measuring Methods of Pay as you throw system in Seoul

| Classification | General Waste | Food Waste |

| Measuring Methods | Standard Bags |

RFID based Weighing System Chips or Stickers Standard Bags |

| Kinds of Standard Bags | General: 3ℓ, 5ℓ, 10ℓ, 20ℓ, 30ℓ, 50ℓ, 75ℓ, 100ℓ Reuse: 10ℓ, 20ℓ Public: 30ℓ, 50ℓ, 100ℓ |

General: 1ℓ, 2ℓ, 3ℓ, 5ℓ, 10ℓ * Over 20ℓ can be used when large amount of wastes is discharged in holidays, Kimchi-making season, etc. |

| Colors of Standard Bags | General and Reuse: White Public: Blue |

General: Yellow |

| Materials of Standard Bags | PE Bag Biodegradable Bag |

PE Bag Biodegradable Bag |

| Examples |  Standard Bags for General Waste |

RFID Based Waste Weighing System |

Background of Introduction of Pay as you throw system

Lots of products led to increased amounts of waste. Meanwhile, Seoul, the capital city of Korea, could not secure the space for landfills to treat wastes any more while the space of Seoul was being expanded to the outskirts of the city.

As the capacity of Nanji Landfill (operated from 1978 to 1993) was reaching its limit, the central government led a project to establish new waste treatment facilities in the metropolitan area to treat the waste from Seoul, Incheon and Gyeonggi-do (province) in 1989. But it was very difficult to move forward because of the strong opposition from the residents living the areas near the expected sites for facilities.

The Seoul Metropolitan Government also planned to build 11 incineration facilities to treat all daily waste from Seoul, but encountered opposition from neighboring citizens and strong voices of the civil societies concerned about excessive facility construction. In 1996, Seoul managed to complete the construction of incineration facilities in Yangcheon (400 tons per day) and Nowon (800 tons per day), and just 4 more facilities (2,850 tons per day) could be built after that. In order to address the issues of waste which had increased in quantity and had deteriorated in quality, the government started to have interest in waste recycling as an alternative mean.

Recycling boxes had appeared in the apartment complexes of Seoul in 1990, and began to be provided to detached house areas the next year. However, the citizens were not familiar with the separate discarding for recyclables. In the case of the detached house areas, half of the collected recyclables was general garbage. On the other hand, the changes in the waste management system costed a lot of money, using landfills a long distance away, constructing incineration facilities, separating the waste into general garbage and recyclables to be collected in different ways, etc. As shown in the data from 1991, the financial expense spent in the waste management was KRW 280 billion and the fee revenue was only KRW 25.4 billion, covering just 9% of the total costs. Most of the expenses for waste treatment were taken by the general account budget, and the part paid by the citizens, the waste generators, was very small. (The Seoul Metropolitan Government, 1992)

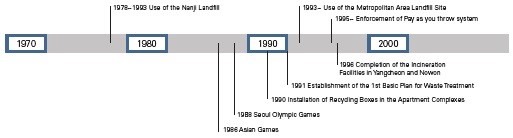

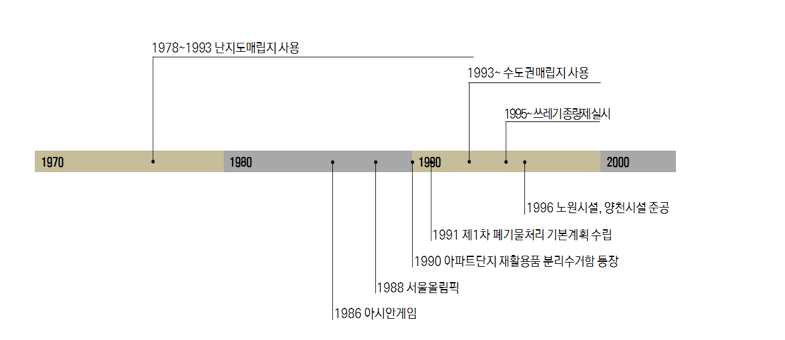

<Figure 1> Main Waste Management Projects before and after the Introduction of Pay as you throw system

However, the fees for waste disposal in Seoul had been collected in a kind of tax form based on the building areas or property taxes which had nothing to do with the amount of waste produced before the pay as you throw system was introduced in 1995 (Ki-young Yu and Jae-cheon Jeong, 1995). The pay as you throw system taken as the waste disposal fee system through establishment of social atmosphere, creation of implementation conditions, pilot projects, etc. has gone through changes and development until it reached its current form.

<Table 2> Waste Disposal Fee Systems of Seoul When Introducing the Pay as you throw system

| Period | Kinds of Waste | Fee Rates | Basis of Charging Fees |

| In the 1980s | General Waste (Small Amount) | 7 | Total Ground Area of Buildings |

| General Waste (Large Amount) | - | Weight | |

| Business Site Waste | 6 | Total Ground Area of Buildings | |

| In the Early 1990s | Household Waste | 9 | Total Ground Area of Buildings /Amount of Property Tax |

| Business Site Waste (Large Amount) | 2 | Weight | |

| Business Site Waste (Small Amount) | 6 | Total Ground Area of Buildings | |

| 1994 (Just before the Introduction of Pay as you throw system) |

Household Waste | 9 | Total Ground Area of Buildings |

| Business Site Waste (Small Amount) | 6 | Total Ground Area of Buildings | |

| Business Site Waste (Normal Amount) | 1 | Volume | |

| Business Site Waste (Large Amount) | 2 | Volume | |

| Construction Waste | - | Volume | |

| Home Appliance | 7 | Kind, Volume | |

| Furniture | 7 | Kind, Volume | |

| 1995 (Enforcement of Pay as you throw system) |

General Waste/Food | - | Size/Number of Standard Bags |

| Large Waste | - | Kind/Size/Number | |

| Recyclable Items | - | Free |

History

- Preparation Stage (1992~1994)

Public hearings and meetings with private organizations consisting of relevant experts, cleaning companies, etc. (Feb. ~ Jul. 1993), meetings with the consumer groups, groups of housewives and waste bag manufactures (Jul. 1993), meetings with the managers of the urban and provincial cleaning departments and opinion collection of the waste subcommittees (Jul. ~ Aug. 1993) were held during the process. Inquiry about the opinions of related organizations and institutes on the legal status of standard waste bags was also conducted (Sep. 1993). The result was that the waste bags could be regarded as official documents as long as the positions of mayor or district heads as well as the marks of the city hall or the autonomous district offices were on the bags, and that it would be considered forgery of official documents if anyone forges and sell the bags.

One year before the pay as you throw system was introduced in country-wide, pilot projects were conducted in 33 cities, counties and districts (Apr. ~ Dec. 1994). In Seoul, Jung-gu as a commercial area, Seongbuk-gu as a detached housing area and Songpa-gu as an apartment area participated in the pilot projects (The Seoul Metropolitan Government, 1994). Before that, the central government announced the implementation measures of the pay as you throw system, including the amounts of the waste fees, how to distribute the standard bags, how to treat the expected increase of recyclables, etc. (Nov. 1993).

During the pilot projects, the government concentrated on finding the waste discarding status, standard waste bags, degree of citizens’ participation, flow of the community opinions, etc. The government assembled a civil assessment team consisting of 7 civic groups including YWCA, YMCA, Green Korea United, the Korean Federation of Environmental Movement, etc. and 165 monitoring agents to provide the ability to assess and report the status of the projects. There were big concerns about negative factors, such as illegal waste dumping, however the positive assessment was dominant due to the 40% reduction of waste amount, 100% increase of recyclables collection, reduced cleaning cost, social expansion of awareness about waste reduction, inspiration of self-confidence of the officials, etc.

Based on the problems that appeared during the implementation of pilot projects, the government made “Guidelines of Pay as you throw system” (Sep. 8th, 1994) to enforce the system on a national scale. On November 7th, 1994, the government held a meeting with the related urban and provincial officials to conduct an interim evaluation on the project implementation of the local governments. On December 7th of the same year, the government issued guidelines of how to fix the problems that were discovered during the interim inspection such as the basic plans to handle the expected rapid increase of regional processing of recyclables, emergency transportation period setting against the emission of large amount of waste just before the enforcement of pay as you throw system at the end of the year, the reinforcement of manpower to facilitate the pay as you throw system, etc.

In addition, the government processed the revision and amendment of related ordinances, management of waste bag manufacturing, designation of the stores to sell the bags, public relation activities, etc. in preparation for the introduction of pay as you throw system on January 1st, 1995. In particular, the government carried out a public relation campaign to ease the citizens’ complaints of “why we should pay for waste disposal?” via media outlets such as TV commercial programs, advertisements in the daily press, TV talk shows, etc. and made and distributed promotion materials like VTR tapes, PR books, posters, etc. (Ministry of Environment and Korea Environment Institute, 2012)

<Figure 2> Main Projects in the Process of Introducing the Pay as you throw system

| 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

| ∎ Sep. 1992~Jan. 1993 Feasibility Study for the Introduction of Pay as you throw system |

∎ Feb. ~ Aug. 1993 Opinion Collection from all walks of life ∎ Sep. 1993 Confirmation of the Official Status of Standard Bags ∎ Nov. 1993 Preparation of Guidelines for the pilot projects |

∎ Apr. ~ Dec. 1994 Pilot Implementation: Jung-gu, Seongbuk-gu and Songpa-gu in Seoul ∎ Monitoring of the pilot projects by the civic assessment team ∎ Preparation for nationwide enforcement ∎ PR for the nation |

∎ Jan. 1st, 1995. ~ Enforcement of the Pay as you throw system on a national scale |

- Introduction Stage (1995)

In the beginning stage of the system, the citizens seemed to not adapt to the implementation of the volume-rate waste disposal methods. There were many cases where the citizens could not distinguish recyclables from general household waste. Out of selfishness, citizens dumped household trash prior to the enforcement of pay as you throw system. They especially discarded large waste like cabinets, refrigerators, etc. at the same time to intensify the confusion. However, these things happened often only in the early stages, and became stabilized as time went by.

In April 1995, the government had an evaluation meeting 100 days after the implementation of pay as you throw system. During the period, a survey of 1,000 households was conducted and the results showed that the citizens appeared to almost fully adapt to the system in a month after the implementation. 98.6% of the respondents had evaluated that they practiced the system well, and the capacity of the most widely used standard bags was 10ℓ, 5ℓ and 20ℓ in order.

The improvement and complement points proposed in the evaluation meeting were strength and convenience of the standard waste bags, application of the system to the wastes in public places, enhancement of convenience for separate collection of recyclables by showing the recycling mark, timely collection of recyclables, prohibition of collection of recyclables that were mixed with the waste, prohibition of excessive packaging of disposable products and preparation of its basis, initiative practice of the system in government organizations, preparation of the criteria for penalty enforcement, establishment and expansion of recycling networks, securing the appropriate price of standard bags, linkage of allotment/deposit for the pay as you throw system, supply and promotion of system related information, etc.

- Development Stage (After 1996)

First, the most troublesome problem in the beginning stage was how to handle the collected recyclables. It was resolved by enacting the producer responsibility regulation in 2003. The recyclables are divided into paper, plastic containers, scrap metal (including cans) and glass bottles. Under the pay as you throw system, the amount of collected recyclables increased but the demand for recyclables was the same. The producer responsibility regulation had been executed using the deposit system for a limited number of items including paper packs, PET bottles, iron cans, glass bottles, etc. However, the system did not work well enough to be of help to increase the demand for manufacturing, because many manufacturers gave up the deposit.

Thus, the government decided to convert the deposit system to an expanded producer responsibility scheme, which required the producers to treat the recyclables. Additionally, the relevant items were greatly expanded to include paper packs, plastic containers, scrap metal (including cans), glass bottles, large sized home appliances, small sized home appliances, fluorescent lamps and batteries. As a result, the supply and demand of recyclables were dramatically improved.

In 1997, the government started to make and provide waste bags exclusively for waste that was difficult for both discarders and collectors to handle. The special waste bags were used to hold broken glasses, small amounts of construction waste, etc. that are sharp and heavy enough to cause physical damage, especially in the process of collection. The special bags were made of tough and easy-to-handle materials (poly propylene) different from those used for the general waste bags.

The standard waste bag, as the core method for implementing the pay as you throw system, was a very convenient tool for measuring the amount of waste in a large city like Seoul, Korea where it is difficult to identify the discarders. But many people pointed out repeatedly that the waste bags were disposable products and became waste after a single use. In order to address the problem, the government recommended selling standard bags for goods transport at large supermarkets (E-mart, Homeplus, Lotte mart, National Agricultural Cooperative Federation or Nonghyup Hanaro Club and Mega Mart). The large supermarkets located in Seoul began to sell the standard bags in 2010. The bag was called the reusable bag, consumers could use it as a standard waste bag, and the price of the reusable bag was same as the standard bag selling at other stores.

The most innovative development was the introduction of the weight-rate waste disposal system to weigh food waste. Many autonomous districts could not apply the principle of pay per disposal system properly in the case of food waste. Most of the districts used the standard boxes for the food waste, and imposed the same fees to all households regardless of the amount of waste. Some districts collected food waste free of charge. There were reasons for their methods. The material of standard bag was polyethylene, which would become foreign material in the process of food waste treatment, lowered the quality of feed or compost made from the food waste, and made the feed or compost consumers reluctant to buy. The districts were confused because they were not sure of the validity of imposing fees for the collection of food waste that could be treated only using the garbage recycling methods, while they were collecting the recyclables free of charge.

However, too much food waste was generated, and it was difficult to turn the food waste into recycled resources and to apply the expanded producer responsibility scheme while taking care of the food waste. Thus, the government decided to introduce the weight-rate waste disposal system in order to reduce the amount of food waste. The Seoul Metropolitan Government also enacted the system in 2003 (The Seoul Metropolitan Government, https://seoulsolution.kr).

The government recommended that the system should operate not on the basis of volume, but on the basis of weight when treating food waste because food waste is heavier than general waste. As a result of this change, it was reported that food waste was reduced by 10~30% (Korea Institute of Industrial Relations and Korea Environment Corporation, Dec. 2013). By using this system, the amount of food waste is recorded by each individual when the food waste is discarded. Based on the recorded information of each individual, the monthly fees are imposed. However, this system is currently only operated in a portion of apartment complexes, because the installation and operation of the weighing system costs a lot and requires space for the installation. For detached houses and restaurants, the standard bags or standard tanks with chip attached are generally used. (Resource Recirculation Bureau of the Ministry of Environment, Nov. 2012)

<Table 3> Methods and Features of Food Waste Disposal Systems

| Item | RFID Weight Method | Chip Method | Standard Bag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition of Discarder |

Electronic Tag/Electronic Card | NA | NA |

| Measuring Unit | Weight | Volume | Volume |

| Storing Container | Individual Container | Individual Container | Bag + Base Container |

| Imposition of Fees | By Household/Restaurant | By Household | By Household |

| Payment of Fees | Deferred Payment | Advance Payment | Advance Payment |

| Waste Reduction Effect | 9~31% | 14% | 13% |

| Remarks |  RFID based Weighting System |

Chip Attached to the Standard Tank |

Standard Bag |

<Figure 3> Sourcebook Regarding the Achievement Monitoring of Waste Disposal System and Improvement of the Implementation Methods

Achievements

Acceleration of Waste Reduction

Of course, there were different arguments for the reduced wastes. According to an opinion, other factors besides the pay as you throw system such as the rapidly reduced use of coal briquettes and the regulatory policy on disposable items and product packaging affected waste reduction (Yong-seon Oh, 2006). On the contrary, another study showed that even when the other factors are considered, it was the waste disposal system that clearly brought about the reduction in waste (Kwang-ho Jeong et al, 2007). The controversial evaluations above were not on the waste reduction itself, but on the size of the system’s effect. The citizens became more sensitive to exaggerated packaging when choosing products, took only the products, leaving the packing materials, and requested to return the packing materials of delivered products. These reactions of the consumers influenced manufactures and were reflected in product design. After the introduction of pay as you throw system, it was obvious that there were changes in the consumption pattern and those changes were admitted by all.

<Table 4> Change of Waste Amount before and after the Enforcement of Pay as you throw system

| Classification | 1994 (Preparation) |

1995 (Enforcement) |

1996 (2nd Year) |

| Generation Amount (tons/day) | 15,397 | 14,102 | 13,685 |

| Generation Amount (kg/day) | 1.43 | 1.33 | 1.31 |

Facilitated Separation of Recyclables and Early Adaptation of Waste Separation

<Table 5> Change of Recycled Waste Amount before and after the Enforcement of Pay as you throw system

| Classification | 1993 (Fixed Ratio) |

1994 (Preparation) |

1995 (Enforcement) |

1996 (2nd Year) |

| Waste Amount (tons/day) | 16,021 | 15,397 | 14,102 | 13,685 |

| Recycled Amount (tons/day) |

2,940 | 3,156 | 4,131 | 4,037 |

| Recycling Rate (%) | 18.4 | 20.5 | 29.3 | 29.5 |

Securing the Waste Management Expenses with Fees

<Table 6> Change of Waste Fees according to the Enforcement of Pay as you throw system

| Classification | 1993 (Fixed Ratio) |

1995 (Enforcement) |

1995/1993 |

| Fee Income (KRW Mil.) | 119,912 | 153,638 | 1.28 |

Creation of Economic Benefit

<Table 7> Change of Fees According to the Enforcement of Pay as you throw system

| Classification | Increase/Decrease Amount (1996-1994, ton/year) |

Benefit per Unit (KRW/ton) |

Scale of Benefit (KRW Bil./year) |

| Reduction | -624,880 | 144,071 | 90 |

| Recycling Amount | +321,565 | 18,901 | 6.1 |

| Total Benefits | - | - | 96.1 |

Meaningful Experiences

- Thorough Preparations

To cope with this negative atmosphere, it was necessary to remove the institutional obstacles in advance, to create an amicable social atmosphere for the system, to find the effects and the problems through implementing pilot projects and to persuade the people of the benefits. In particular, it was imperative to find the system implementation methods suitable to each city in during preparation stage. In the case of Seoul, it was not easy to identify the waste discarders because there were many high-rise buildings such as apartments and shopping centers and the city space was small and narrow. That was the reason why Seoul took the standard waste bag as the method to measure the amount of waste.

However, it was desirable to use baskets only for the waste in regions with many detached houses and developed roads because it was possible to prevent the waste of disposable standard bags and illegal dumping by making an agreement with all dischargers on the size of waste baskets and to reduce the waste collection cost by introducing the automated basket loading vehicle system.

Cooperation with the Civil Society

The civil society has taken part in the evaluations for the pilot project and the first, second and tenth years of the system implementation persistently. Even now it is involved in the process of assessment for the implementation of the food waste disposal system. The positive evaluation from the civil society has contributed greatly to the change of the attitude of the mass media and the national consciousness.

Securing the Disposal Paths for the Increased Amount of Recyclables

The issue was solved in 2003 when theE government gave financial support to help the plastic recycling operators install and operate the relevant facilities, made the public sectors purchase recycled plastic products preferentially, and to impose the obligation to collect and process recyclables which had weak treatment basis in the market (including the plastic containers) to the manufacturers (Extended Producer Responsibilities Scheme).

With the introduction of pay as you throw system, an unplanned recycling item was added. Because of the serious bad smell from the landfills, lots of complaints were raised one year after the system’s introduction. The same complaints were made about the roads to the waste treatment facilities. The cause of the problems was food waste. The large amounts of papers acted as buffers in standard bags, absorbing the leachate and blocking the smell of the food waste to some degree, but the papers were classified as one of the recyclable items.

The main cause of the bad smell was the fact that papers were no longer discarded with general waste. The problem was resolved by collecting the food waste separately and changing the treatment system on a large scale. Landfill of all food waste was prohibited from 2005. The government started the construction of food waste treatment facilities in 1998. Seoul has 5 public facilities to treat food waste in five places now. The remaining food waste is processed using private facilities.

Prevention of Illegal Acts

The illegal dumping was reduced a lot, but not eliminated though. In the meantime, the systems to impose penalties for committing illegal acts and to supply standard bags to the low-income class free of charge were prepared.

<Figure 4> Cases of Illegal Dumping and Corresponding Measures

Illegal Waste Dumping in Suburbs (http://waste21.or.kr) |

Disposal Using Non-standard Bags (http://waste21.or.kr) |

Creation of Flower Beds (http://dong.jungnang.seoul.kr) |

.png) Installation of Reflectors (http://www.cpdc.re.kr) |

- Revision of Legislation

Each district covers the specific regulations on how to enforce the system in its own ordinance. It regulates the kinds of waste under the application of the pay as you throw system, discharging methods, fees, kinds/colors/materials of the standard bags, supervision of standard bag manufacturing and safe management, designation of the stores to sell standard bags, guidelines for standard bag sellers, criteria on the cancellation appointment of standard bag sellers, etc.

The size, material, strength and kind are determined based on the Korean Standard on Plastic Products. All specifications of standard bags are subject to the standard and standard bags made against the standard cannot pass the inspection. To prevent the counterfeiting of bags, the seals for printing on the surface of standard bags were kept by the autonomous districts and handed over to the manufacturers only when they produced standard bags. In the case that a person makes and distributes counterfeit bags, the person would be punished according to the regulation on the fabrication of official documents under criminal law.

<Table 8> Legal Systems Related to the Enforcement of Pay as you throw system of Seoul

| Classification | Description |

| Waste Management Act |

|

| Ordinance on the Waste Management of the Autonomous Districts |

|

| Korea Standard on Plastic Products |

|

| Reports on the Performance |

|

| Criminal Law |

|

References

- Future Environment, Rampant Food Waste Dumping in the Food Waste Bag System Enforced Areas: Status Survey of Resource Circulation Society United, Max 1.42 Case by Dong, http://www.ecofuturenetwork.co.kr

- Graduate School of Environment of the Seoul National University, 1983. Study on the Efficient Management of Solid Waste in the Cities

- The Seoul Metropolitan Government, 1992, 1992 Administration of Seoul

- The Seoul Metropolitan Government, 1994, Detailed Guidelines for the Pay as you throw system

- The Seoul Metropolitan Government, RFID Food Waste Disposal System, Seoul Policy Archive (https://seoulsolution.kr)

- Yong-Seon Oh, 2006, Critical Evaluation on the Environment Improvement by the Pay as you throw system, Korean Policy Studies Review, 15(2):245-270

- Ki-yeong Yu and Jae-cheon Jeong, 1995, Problems of Fixed Ratio Fee System and Effects of Pay as you throw system: with Seoul as the Center, Journal of Korean Environmental Engineering, 17(9): 907~915

- Beon-song Lee, Ji-wuk Kim, Ki-young Yu and Sang-hu Park, 1996, Evaluation of the Pay as you throw system and Improvement Methods

- Jeong-jeon Lee, 1991, Study on Policy Improvement to Facilitate Environmental Improvement, Seminar Materials of International Trade Management Research Institute

- Our Dong News, Junghwa 1-dong, Jungnang-gu, http://dong.jungnang.seoul.kr

- Chungnam Public Design Center, Public Design Creation Projects of the Local Governments, http://www.cpdc.re.kr

- Waste 21, Illegal Dumping in the City Outskirts, http://waste21.or.kr

- Korea Institute of Industrial Relations and Korean Environment Corporation, Dec. 2013, Study on Performance Evaluation of Food Waste Disposal System and Development Plan

- Resource Recirculation Bureau of the Ministry of Environment, 2012.11, Guidelines for Pay as you throw system including Food Waste Discharge and Fees

- Ministry of Environment, 1997.5, Guidelines for Enforcement of Pay as you throw system

- Ministry of Environment, 2012.11, Guidelines for the Volume-rage Waste Disposal System

- Ministry of Environment· Korea Environment Institute, 2012, 2011 Modula Modularization Program of Economic Development Experiences: Volume-rate Waste Disposal Policy

- Minister of Environment, 2011, Guidelines for the Separate Collection of the Recyclables, etc., (Order No. 859 of Ministry of Environment, 18 Aug. 2009)

Policy Implementation Period

- 1994 Piloted Volume-based waste disposal system (Commercial arcades - Jung -gu, detached housing area –Seongbuk-gu, apartments- Songpa gu)

- 1995 Volume-based waste fee system launched (The first implementation at the national level)

- 2010 Reusable VBWF bags in place

- 2013 Volume-based food waste fee system launched

Figure1. Seoul’s Waste Treatment before and after the Launching of the Volume Based Waste Fee System

Source: The Seoul Institute (2015)

Background Information

In the meanwhile, due to the shift in the tendency of huge population, who used to flock to Seoul for living and work, started moving out to the suburb area, Seoul’s neighbouring cities were turning into new towns accommodating Seoul’s excess population. As a result, it got more difficult to secure landfill sites in the suburb and even impossible to do so in Seoul, which had been major waste treatment facility. Gyeonggy Province and City of Incheon were not exception in having difficulties in securing landfill sites. Government took the lead in promoting the establishment of the landfill sites (Sudokwon Landfill Site) where Seoul, Gyeonggi province and Incheon could share. However, it was not smooth at all to establish the Sudokwon Landfill Site as the sense of repulsion towards non-preferred facilities like landfills was already widespread.

While going through difficulties in securing landfill sites, Seoul established a waste treatment plan with the focus on reducing dependence on landfills in 1991. The plan mainly covered constructing 11 incineration facilities. However, even that plan was severely opposed by residents of designated facility area. Civic groups pointed out problems in the plan arguing the size and the number of planned incinerator facilities construction was excessive. So far, as a result, 4 incinerator facilities have been built in Seoul.

As an alternative to reducing waste volume to be buried, recycling policy had been promoted. In 1990, the recycling bin started to be installed in apartment complexes. Due to a level of success so the bins were installed in detached houses area as well. However, residents were not accustomed to separating recyclables from garbages so it was not unusual to find the trash from the recycling bins.

It required a huge amount of costs to construct incinerator facilities and promote recycling in order to overcome the situation where landfill sites got farther away from the downtown. In 1991, Seoul and autonomous gu (administrative district, borough) spent a whopping 280 billion KRW in waste management while residents spent only 25.4 billion KRW. Residents, who discharged the garbage, shared only 9 percent of the costs in waste management.

Due to such situations in 1980s and 1990s, government was desperate in finding ways to invite active public participation in recycling and charge the public more for the growing costs of waste treatment.

Volume-based waste charge system is a sort of solution based on ‘The Polluters Pay Principle.’ The theory supporting the need for the volume based waste charge system had already been raised in 1980s. However, before the volume based system was in place, waste treatment fees were levied based on the gross area of the building or on the property tax. Back then, waste treatment fees were collected as a type of tax. Table 1 below summarizes the changes of the waste charge systems up until the implementation of volume based waste charge system in 1995.

Table 1. Seoul’s Waste Fee System until 1995

| Year | Waste Type | Fee Grade | Basis for Fee Imposition |

| 1980s | General Waste (Small quantity) |

7 | Building’s Total Floor Area |

| General Waste (Large quantity) |

- | Weight | |

| Business Waste | 6 | Building’s Total Floor Area | |

| Early 1990s | Residential Waste | 9 | Building’s Total Floor Area/Property Tax Amount |

| Business Waste (Large quantity) |

2 | Weight | |

| Business Waste (Small quantity) |

6 | Building’s Total Floor Area | |

| 1994 (Preparation Period ) |

Residential Waste | 9 | Building’s Total Floor Area |

| Business Waste (Small quantity) |

6 | Building’s Total Floor Area | |

| Business Waste (Medium) |

1 | Volume | |

| Business Waste (Large quantity) |

2 | Volume | |

| Construction Waste | - | Volume | |

| Discarded Home Appliances | 7 | Type․Volume | |

| Discarded Furnitures | 7 | Type․Volume | |

| 1995 (Implemented Year) |

Genearl/Food Waste | - | Size/Number of standard Trash Bag |

| Bulky Waste | - | Type/Size/Number | |

| Recyclables | - | Free of Charge |

The Importance of the Policy

VBWF system has been designed to charge in proportion to the amount of discharged waste and to the costs required in the waste treatment. People are induced to reduce the waste amount on voluntary basis. Wastes discharged as reclyable goods are exempted from collection fees, thus inducing recycling from separate waste collection, which is good both for the residents and authorities. Reduced amount of discharged waste means reduced fees for the residents and also means less dependency on the incinerating facilities and landfill facilities. VBWF system is meaningful as a policy as it changes residents’ patterns of waste disposal.

The efforts to change citizens’ pattern of waste disposal by awareness campaign or education may be more convenient but may not gain desired results or may gain, yet, very slowly. As a way to control behaviors against environmental protection, government rules and regulations have long been resorted to but enforcement requires human resources, giving rise to high cost for the policy implementation or due to insufficient number of personnel, enforcement had not been conducted. Regulation-oriented approach may not encourage consumers to make voluntary efforts to reduce pollution lower than permissible level. On the contrary, when residents are encouraged to change their behavioral patterns by gaining economic incentives (via VBWF system) proportional to the amount of the reduced amount of discharged waste, residents are motivated to reduce the waste more. After all, VBWF is a very environmentally desirable and effective way to bring about changes in behavioral patterns of residents.

Relevance with Other Policies

Therefore, it is very important to make a reasonable estimation and strike a balance between the amounts of waste to be generated, waste to be recovered as resources, and waste to be processed by burning or burying. Particularly, VBWF system has direct impact on other relevant waste management policies including policies on waste management facilities as VBWF system makes a huge contribution to suppressing waste in the first phase, waste generation, of the waste management policy.

Until 1980s, private sector took the lead in the recycling market whose focus had been collecting discarded papers, scrap metals and glass bottles. Recyclable wastes were collected by junk men. To the low income people, scavenging for recyclable items had been a crucial means of livelihood at the Nanjido landfill. Recycling bin installed by civic groups and Korea Resources Recovery and Reutilization Corporation (KORECO) started to appear by the time when it was hard to secure landfill site and incineration facilities had become controversial in 1990.

The recycling bin started to spread across detached house area since 1992. As social conflicts got intensified over incineration facilities and waste landfill, high expectation were pinned on turning the wastes into recyclable items as alternatives to incineration and reclamation. Obviously, the separate disposal and collection of wastes and recyclables had not been settled as it was not unusual to find wastes mixed in the recycling bins or recyclables items in the waste bags. The VBWF system implemented since 1995 had solved such problems. The VBWF system implemented in Korea has been remarkably effective in settling the separate collection and disposal of voluminous papers, plastic containers and cans, which requires purchasing standard waste bags to throw away their garbage, thus waste collection fee is charged in proportion to the amount thrown away.

The government revised the Waste Management Act in 1998 saying starting in 2005 so the direct land-filling of food waste generated in urban areas would be completely banned. With the implementation of the VBWF system, residents living around waste treatment facilities including incineration and landfill site expressed opposition to the facilities, as food waste was discharged using the VBWF bags, which gave rise to the various environmental problems including creating serious foul order and harmful insects.

Meanwhile, autonomies, responsible for the MSW, faced more difficulties when supply of recyclables increased. It was not unusual to see recyclable items piled up in the regional authorities’ recycling depository as there was no available market for the recycled goods. Also, due to free-fall of trade prices, private sector refused to purchase the recyclable items. Selecting and securing food waste treatment facilities were also serious headaches as residents around the would-be facility sites were deadly opposed to them and the other option of using private facilities were simply too expensive.

In the end, VBWF system had met the policy goals of waste reduction and separate disposal and collection of recyclable wastes but it generated the demand for policies such as securing markets for supply and demand of recyclable markets and establishing food waste management facilities, which led to the introduction of Expanded Producer Responsibility (EPR) in 2003 and ban on the direct land-filling of food waste in 2005.

Policy Objectives

- Reduced waste generation at source

- Settlement of separate disposal and collection of recyclable items.

- Reduced dependence on the waste processing facilities (incinerating facilities and landfill facilities)

Main Policy Contents

General waste refers to waste to be incinerated or to be buried. Waste volume is measured through standard garbage bags, which were taken by the district, or gu, offices to be divided into household, commercial, and business use. Bags are in 2, 3, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, 75, and 100 liter sizes, with people able to purchase the size and quantity of bags they wish at designated stores. General waste therefore is treated based on volume based charge system.

Food waste could be discharged in various ways. People may use standard waste bags sold by local authorities, standard plastic container equipped with electronic chip or sticker, and weight-based payment using electronic card with RFID. In the case of RFID based food waste treatment, discharger should swipe a card before gaining access to residential waste bins. The chip containing user’s name and address allows the authorities monitor the weight of individual’s waste. The system accumulates the fee on a monthly basis, and each household receives a monthly food waste disposal bill.

Other items such as papers, plastic packaging materials, glass bottles, scrap metals, discarded home appliances, discarded florescent lamps, used batteries and used cooking oil are classified as recyclables and should be discharged in the way prescribed by the Ministry of Environment.

Table 2. Seoul’s Way to Measure and Charge IAW VBWF system

| Category | General Waste | Food Waste |

| How to Measure |

|

|

| Types of VBWF bags |

|

|

| Colors of VBWF bags |

|

|

| Materials of VBWF bags |

|

|

However, ordinary VBWF bags are little better than disposable trash bags which could be used only once. The Korean Government, for its part, as an effort to solve, albeit partly, such issue, allowed shopping giants such as E-mart, Home plus, Lotte mart, Nonghyup Hanaro mart, Mega mart to offer the reusable VBWF bags and customers could use them as standard trash bags.

Since 2013, food waste has been subject to volume-based waste fee system in Seoul. The chip or sticker system requires a discharger to buy a payment chip or sticker and attach it to a standard collection container to be picked up. The container serves as a disposable volume measuring device or monthly volume measuring devices. The merit of RFID system is that it accurately scales waste volume and fees are charged according to the total volume. However, RFID system could be quite complicated as it has to be equipped with weight measuring device, discharger recognition system, and volume tracking & storage devices.

When disposing large items, discharger should buy sticker from the regional authorities and place it on the item before they are picked up, or let them be picked up by garbage haulers.

Discharge Fees

Policy Effects

1) Reduction of Household Solid Waste Generation

According to Seoul’s statistics, the volume of waste generated in Seoul had been reduced by 8 % in 1995 and 11% in 1996 compared with that in 1994, which was tantamount to reduction of 1,1712 ton/day. Since the VBWF system has been instituted, consumers have shown changed pattern of waste generation, improved awareness of waste disposal, which well explains the cause of the reduction in statistics. For example, consumers got sensitive to over-packaging of products, brought only product part, while leaving the package materials at the sales shop, requested the collection/return of packaging material when delivered, which, in turn, affected product design. Some quarters, of course, argued the waste reduction was hardly due to the VBWF system, but due to reduced consumption of coal briquette, changes of charging basis from volume to weight, dwindled production and consumption in the wake of economic crisis that hit Korea hard in 1998 and the Government’s separate implementation of relevant policy. However, reduced waste generation was a very natural consequence of the policy considering the principle of environmental policy, VBWF system. Therefore, the level of the policy effect could be controversial but it does not make sense to argue against the effect per se.

Table 3. Changes in the Waste Generation

| Change | 1994 (Preparation Period) |

1995 (Implemented Year) |

1996 (Institutionalization Period) |

| Generated Volume (ton/day) | 15,397 | 14,102 | 13,685 |

| Generated Volume (kg/day) | 1.43 | 1.33 | 1.31 |

2) Contribution to the Settlement of Separated Disposal and Collection of Waste and Recyclable Goods

Recycling performance (the recycled amount) in 1996 had increased by 881 ton/day compared with that in 1994. Out of overall waste treatments, the recycled volume had shown significant rise from 20.5% in 1994, to 29.3% in 1995 (the year VBWF system was introduced), to 29.5% (2 years into the introduction of VBWF system). The separate disposal and collection of wastes and recyclables had led to reduced demand for waste treatment facilities.

Table 4. Changes in the Recyclables Generation

| Category | 1993 (Flat Rate) |

1994 (Preparation Period) |

1995 (Implemented Year) |

1996 (Institutionalization Period) |

| Waste Generation (ton/day) | 16,021 | 15,397 | 14,102 | 13,685 |

| Recyclables Generation (ton/day) | 2,940 | 3,156 | 4,131 | 4,037 |

| Recycling rate (%) |

18.4 | 20.5 | 29.3 | 29.5 |

3) Securing Waste Treatment Costs from Profits of VBWF System

Table 5. Changes in Profits from the VBWF System

| Category | 1993(Flat Rate) | 1995 (Implemented Year) | 1995/1993 |

| VBWF Revenues (million won) |

119,912 | 153,638 | 1.28 |

4) Creation of Economic Benefits

Table 6. Changes in Discharger Fees

| Category | Changes (1996-1994, ton/year) |

Benefits (KRW/ton) |

Scale of Benefits (billion KRW/year) |

| Reduced Amount | -624,880 | 144,071 | 900 |

| Recycled Amount | +321,565 | 18,901 | 61 |

| Total Benefits | - | - | 961 |

Challenges and Solutions

1) Supply of Collected Recyclable Waste

Recyclable wastes are categorized into papers, plastic containers, scrap metals (including can) and glass bottles. The VBWF system, which stipulates collection of recyclable goods for free, helped settlement of the separated discharge and collection of recyclables in a short period. In the meanwhile, recyclables had not been well utilized, which became the burden of the government. In particular, main headache was how to make use of plastic containers (made of PE, PP, PS or PVC) except PET. Even though they are designated as recyclables but those recycling infrastructure for plastic materials was inadequate. Moreover, as VBWF system virtually focused on charging plastic containers, producers were not responsible for the recyclable waste. The deposit-refund system was in place, which levied a refundable container deposit on consumers. However, that system applied to only a few limited items including paper pack, PET bottles, iron can and glass bottles. Unfortunately, many producers gave up on the deposit, so the deposit-refund system did not really help supply and utilize the recyclable wastes.

Solutions

In addition, products manufactured using recycled plastics were preferentially purchased by the public sector. Also, in 2003 expanded producer responsibility (EPR), replacing the deposit-refund system, was imposed on the manufacturer to resolve insufficient recycling infrastructure for recyclable wastes (including plastic containers), which held the manufacturer responsible for the costs of managing their products at the end of life. Also, the items subject to the EPR have been expanded to include paper pack, plastic containers, scrap metals (including iron can), glass bottles, big and small home appliances, discarded florescent lamps, and used batteries. As a result, the issue of supply and demand of collected recyclable waste had improved dramatically.

2) Food Waste

Difficulties in Implementing VBWF System

Also, autonomous districts had hard time in arguing whether it’s proper to impose charge on food waste which would turn into resources, while recycable items were collected free of charge.

Solutions

Considering relatively heavier weight of food waste, the government has recommended authorities to adopt weight-based waste fee (WBF) system instead of volume-based system and the WBF system has reportedly reduced the food waste by ten to thirty percent. Under the WBF system, the discharged weight of food waste is recorded for each resident and the fees are levied based on the weight tracking record. The devices for WBF system has been installed only in some apartment complexes as it is costly to install and operate weight measuring devices and enough space is necessary for the installation of device. Detached houses and restaurants have widely used VBWF bags for food waste or standard waste bin tagged with chip.

Foul Odor from Food Waste

Solutions

3) Waste Bags

Material

Solution

Environmental Issues

Solution

4) Negative Public Sentiment against the Implementation of VBWF System

Solution

- Thorough Preparation

It is imperative to figure out what type of VBWF system is proper for the city during the preparation stage. Seoul selected VBWF bags as a means to measure the waste volume because it’s hard to identify dischargers in this overpopulated but cramped city with lots of high-rise buildings such as apartment complexes and shopping malls.

However, it could be desirable to use waste bins for area with lots of detached houses and with roads stretching in all directions. Also, the use of waste bins could prevent the waste of throw-away VBWF bags, ward off illegal dumping by concluding contracts with the dischargers on the size of trash bins, and save waste collection fees by using automatic loading system.

- Cooperation with Civic Groups

In the settlement of VBWF system, civic groups in the environmental field had played a crucial role. While the introduction of the VBWF system had been discussed, civic groups were not by and large positive to the idea. They were also worried about fly-tipping not to pay charges for the wastes and were doubtful of government, arguing the government tried to shoulder the entire burden of waste reduction and turning the waste into resources to the general public. However, the civic groups started changing their attitude after they participated in the pilot projects and site monitoring in the year when the VBWF system was introduced, and ascertained publics’ passion for the system. The civic groups had steadily partaken in pilot project evaluation, year one evaluation, year two evaluation, and ten year evaluation. Even nowadays, they have taken part in the progress evaluation of volume-based food waste fee system. Positive attitudes and evaluation of civic groups have made a huge contribution to changing the tone of media coverage and the public awareness of the issue.

5) Illegal Dumping

Solution

In order to prevent littering, some local authorities installed reflectors in vulnerable places, made flower garden, got rid of public waste bins in the down town. Due to such a series of efforts, the number of violations had been dramatically decreased, even though not perfectly eradicated. In addition, penalties were imposed on the violations or VBWF bags were offered to low income family free of charge.

Figure 4. Illegal Activities and Countermeasures

6) Legal Framework for the Institutionalization of Volume-based Waste Fee System

Legal grounds for volume-based waste fee (VBWF) system is ‘Waste Management Act’ and specific implementation of the act is determined by regional authorities’ ordinances. The Waste Management Act includes penalties against the violators.

Each regional authority’s ordinance defines specifics of the implementation which are types of waste subject to the VBWF system, ways of discharge, charge, color and materials of standard plastic bags (VBWF bags), safety management of manufacturing and inspection of VBWF bags, how to designate shops in charge of supply, purchase and sales of the VBWF bags, rules the seller have to follow, the standard of cancelling the designated VBWF bag sales shops.

The size, material, strength and type of the standard litter bags are determined by Korea Federation of Plastic Industry Cooperation (KFPIC). The standard VBWF bags should be manufactured in accordance with the standard of KFPIC and if they fail to meet the standard, they will not pass the inspection.

To prevent the manufacturing and use of fake litter bag, seals stamped on the surface of the VBWF bags are kept by local authorities (or collection and transport agency authorized by the local authorities) and are handed over to the manufacturers only when the VBWF bags are manufactured. If fake bags are manufactured or distributed, violators will be subject to criminal penalties equivalent of fabrication of the official documents.

Table 7. Legal Framework for Implementing Seoul’s VBWF System

| Category | Details |

| Waste Management Act | ‣Recommend the implementation of the VBWF system ‣Establish ordinances relevant to the implementation of the VBWF system. ‣Ban illegal dumping and implement regulations to impose fines to those doing illegal dumping ‣ Revise relevant rules and regulations of the local autonomous governments: rules and regulations of the ordinance, VBWF system implementation guide, VBWF system implementation guide of food waste |

| Regional Autonomies’ Waste Management Ordinance | ‣Contents: Designate wastes subject to VBWF system, ways of discharge, collection fees, color and material of VBWF bags, manufacturing ․inspection․safety management of VBWF bags, shops for the supply, purchase, sales of VBWF bags |

| Korea Federation of Plastic Industry Cooperation (KFPIC) | ‣Type : VBWF bags made of PE, VBWF bags made of LLDPE , VBWF bags containing LDPE (CaCO3+HDPE) ‣9 types of biodegradable VBWF bags |

| Progress Report | ‣Contents: Implementation, manufacturing and sales of the VBWF bags, ways and frequency of waste collection, financial independence of waste management and financial dependence allotment rate, discharge of bulky waste and collection of disposable vinyl bags, enforcement performance of illegal activities and etc. |

| Criminal Law | ‣If fake bags are manufactured or distributed, violators will be subject to criminal penalties equivalent of fabrication of the official documents. |

Promotion of Phased Price Rise of VBWF Bags

Table 8. Basic Price of VBWF bags for General Waste and Food Waste

| Category | Collection & Transport Fee | Treatment Cost | Manufacturing Cost | Sales Profit | Total | Deviation | |

| General Waste | 20L (Basic Price) |

402 | 190 | 51 | 22 | 665 | 1.00 |

| 20L (Currently) | 308 | 12 | 21 | 22 | 363 | 0.55 | |

| Food Waste |

2L (Basic Price) |

142 | 149 | 10 | 4 | 305 | 1.00 |

| 2L (Currently) |

101 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 120 | 0.39 | |

Seoul had good reasons to raise the price of VBWF bags. Above all, Seoul residents’ share of charge included in the price of VBWF bags had been lowest among local autonomies. It cost 665 KRW to dispose of 20 liters of MSW while the price of 20 liter VBWF bag was 363 KRW, which meant Seoul residents paid only 55% of the waste treatment costs. In regards to food waste, situation was even more worrisome. The price of 2 liter VBWF bags for food waste was 120 KRW while the food waste treatment costs for that volume was 305 KRW, residents took only 39% of the cost burden.

Table 9. Nation-wide Average VBWF Bag Prices

| Category | National Average | Average of Metropolitan Cities | Seoul | Busan | Dae-gu | In-cheon | Gwang-ju | Dae-jeon | Ulsan |

| Price (KRW) | 457 | 650 | 363 | 850 | 430 | 620 | 740 | 660 | 600 |

While national average price of VBWF bags was 457 KRW, the price in Seoul was 363 KRW, 80% of national average or the lowest in the nation. Even if we factor into different processing methods and costs for local autonomies, VBWF bags in Seoul were apparently cheaper than in other regions.

As the residents’ share of waste treatment cost was low, district’s financial strain got severer. While the price of VBWF bags had not changed a lot since 1995 (the year the system was introduced), prices kept rising, causing bigger treatment costs. In addition, profits from the sales of the VBWF bags have had a direct impact on the district’s financial condition as starting in 2015 sales profits of the VBWF bags have been directly managed by the districts.

Table 10. Guidelines in the Price Raise of VBWF Bags

| Category | Current Fee | Autonomies’ Average | ’15 | ’17 |

| General waste (20ℓ) | 340KRW~400KRW | 363 KRW | 437 KRW | 492 KRW |

| Food waste (2ℓ) |

40KRW~160KRW | 120 KRW | 133 KRW | 187 KRW |

To resolve such problems, Seoul announced guidelines in the price rise to make different prices of VBWF bags from districts to districts to similar level and in raising the lowest rise of VBWF bags in Seoul in phases until 2017.

In other words, the price of VBWF bags will have been raised gradually and by 2018 the prices of VBWF bags in all the autonomous districts in Seoul would be similar level. Final prices for 20 litter VBWF bags will be 492 KRW and 2 liter volume-based food waste fee bags will be 187 KRW.

To sum up, price rise of the VBWF bags mainly aims to reduce the financial burden of local districts. More fundamentally, it aims to curb waste generation at source.

People would be more discrete in discharging if the VBWF bags are more expensive, or they would go so far as not to generate unnecessary waste in the first place. To curb the waste generation, VBWF system has been instituted and for the same purpose the prices of VBWF have been raised.

Model Cases of Volume-Based Waste Fee SystemThe model cases in Dobong-gu, SeoulSeparate Disposal and Collection of Recyclable Waste Dobong-gu (gu, administrative district) came up with 6 different guidelines depending on the housing types. Basically, the waste collection from apartment complexes made independently by residents while those living in ordinary residential area required district office to be actively involved in the collection and disposal of wastes and recyclables. a) Professional Collection System Garbage collection team was organized in respective sub-districts, dong, and one cleaning personnel and one driver took a recycling waste collection vehicle together to collect the recyclable waste on the road, joined by an official in charge of waste management from the sub-districts office. In addition, they entered into a business relationship with recycling shops. Professional team members brought necessary equipment and collected recyclable materials and sold the recovered materials to the shops. The profitability was maximized and residents’ involvement increased. b) Compensation for Recyclable Materials The Volume-based Waste Fee System represents a right way of waste separation and collection but to the perspective of residents it could be a very inconvenient system. It does not make any sense if the recyclable materials-- which residents separated from trash with much effort -- are to be collected free of charge while residents are asked to bear considerable inconveniences following the system. As compensation (toilet paper) was made for the recyclable materials, residents were motivated to participate and the compensation had a level of promotional effect in a short space of time. c) Separation of 5 types of Recyclable Waste Recyclable waste is separated into 5 types (newspapers, scrap paper, milk cartons, bottles, metals) and there are certain ways of discharging the recyclable waste. Collected waste, already separated into 5 types, could be sold at the recycling shops immediately upon collection. d) Daily Collection Drive in One Single Zone The one-size-fits-all approach was not pursued to the waste collection based on sub-districts, dong, but flexibility was added to the collection process to ensure adjustment of collection methods and schedules, etc. In other words, they divided the entire sub-district into five zones and focused on the promotional drive and thorough waste collection in one zone a day, not covering the entire five zones in a day. The sanitary workers were ordered not to collect improperly discharged garbage at the door and induced the residents to load the garbage bags onto the waste collecting truck when they hear the signature song. e) Collection and Selling on the Same Day As the recyclable materials were collected in the morning and sold in the afternoon, the recyclable waste selection yard were no longer necessary. The recovered recyclable materials, depending on the items, were sold directly to the private recycling shops not only to the public recycling companies. In that way, the profits from the recyclables management were maximized and returned to the residents. f) Implication The key drivers for the success were 1)the active involvement of residents who were encouraged to do what they had to, 2) high proceeds from the sale of recovered recyclable materials by relevant administrative authorities, 3) return of the proceeds to the residents, and 4) efforts by the authorities to motivate residents’ participation. To ensure success, intensive educational session was conducted, hosted by the head of district office. On top of that, instead of perfunctory committee gathering, public officials had face-to-face encounter with residents for promotion of the program. |

References

- Yoo, Ki-young (2015), Seoul Solution Waste, The Seoul Institute , ‘Waste’ section, The Seoul Institute

- Seoul Metropolitan Government, 1992, 92 Seoul City Administration

- Minister of Environment, 2011, Guide in separate discharge of recyclable resources and etc. (Ministry of Environment, Directive, No.859, 2009. 8. 18)

- Ministry of Environment, 2012. 11, Volume based Waste Fee system implementation guide

- Ministry of Environment, Resources Recirculation Bureau, (2012) Implementation guide on volume-based waste fee system for the discharge of food waste

- Sohn, Youngbae(2001), Volume-based waste fee system, Who established it and how did it go? ‘Monthly magazine waste 21’, 2(7) : 1-5

- Oh, yong-sun, 2006, A Critical Evaluation on the Effect of Environmental Improvement by Volume-based Waste Fee System, 「Korean Association for Policy Studies Newsletter」, 15(2) : 245-270

- Korea Institute for Industrial Research·Korea Environment Corporation, (2013). A study on the performance evaluation and development of volume-based food waste fee system

- Ministry of Environment·Korea Environment Institute, 2012, Modularization of Korea's economic development experience : Volume-based wastee fee system

- SBS, 2015. 8. 6, The price of volume-based waste fee bags, should it be raised?