ازالة جسور المشاة في سيول للحفاظ على جمال المدينة وتحسين البيئة.

Background to Removal of Overpasses

Into the 1970s, South Korea achieved dramatic economic growth. With it, the automobile industry also grew. One of the most important transportation policies of the time was to facilitate traffic flow, and overpasses were built in support of this policy. These structures were built mostly in the old downtown area because, at the time, traffic flowed into the city center, within the boundaries of the four old city gates. The urban expressways (e.g., Gangbyeon Riverside Expressway, Olympic Expressway, Oegwak Outer Beltway, Naebu Inner Beltway) did not exist, and all arterial roads headed toward the city center. In the 1970s and 1980s, most overpasses were built in the old town center in Gangbuk where traffic bottlenecks occurred. Eighty-six overpasses were built in Seoul during this time of constant construction.

Three to four decades later, in the 2000s, overpasses began to lose their originally intended function due to more balanced urban development as well as changes in road networks and the overall traffic system. As highly functional roads such as urban expressways were built one after another, traffic dispersed and urban concentration also eased. More than anything, the old town within the four old city gates declined and the new Gangnam areas prospered. This shift in urban concentration and “relocation” of the bottlenecks from old to new areas brought the excessive investment on overpasses to light. For instance, Ahyeon Overpass was empty except during commuting hours and its numerous sharp bends resulted in speed-related accidents. Overpasses such as this, where users were hit with a “congestion charge” to discourage them from bringing their cars into the city center, were no longer the symbol of smooth flowing traffic. The transportation policy paradigm was also changing, and more emphasis was placed on pedestrians and public transit than on vehicles.

Residents argued that overpasses blighted the cityscape, caused regional isolation, and undermined regional development. Accordingly, the argument for removing overpasses became more and more logical, which the City of Seoul began to review. Subsequently, the city decided to remove some of them, starting with the Cheonggye Overpass connecting east and west in 2003. The removal of this first overpass resulted in a better cityscape and traffic congestion was not as severe as had been expected. Since then, the city decided to consider removal of other old, ugly overpasses that undermined the cityscape.

<Figure 1> Removal of Cheonggye Overpass: Before & After.jpg)

Source: Internal data, Seoul Metropolitan Government

Another reason for this was that overpasses interfered with another program in Seoul – introduction of the center bus lane system. To install center bus lanes, a minimum of 2 additional lanes were necessary; most overpasses began at the center of roads that were 4 lanes (both ways) or narrower. Center bus lanes could not be built on roads over which overpasses occupied. On the stretch of roads where overpasses begin, congestion is frequent as cars and buses change lanes to get on their desired path. The local environment was also an element. Most areas with overpasses saw their commercial districts fade away due to the support columns, some areas even becoming slums. Many of these supports have been removed for a myriad of other reasons (deterioration, disruption of traffic flow, interference with subway construction, blighting the cityscape, etc.). More will follow suit.

Summary & Process

Studies by experts show that there were approximately 40 deteriorating overpasses of 30 years of age or older, and that were not as functional as they were intended to be. Although removal of the overpasses would potentially nearly double the traffic volume, this would be compensated by better public transit service, leaving the road’s capacity for cars unchanged. In 2002, Seoul started with Tteokjeon Overpass in Jeonnong-dong and phased out overpasses that were not safe or lacked economic or environmental value, seeking to change public awareness of the changing city, improve the cityscape and urban environment, revitalize affected regions and their commerce, and enhance traffic flow and safety.

One of the best examples of an overpass that outlived its effectiveness in terms of traffic flow is the previously-mentioned Cheonggye Overpass. Built to absorb the explosive traffic inflow in the 1960s, Cheonggye Overpass was removed as part of the Cheonggye Stream Restoration project in 2003. The 5 km stretch was replaced with a one-way 2-lane road with a center bus lane. Before demolition, some worried about severe congestion due to the reduced road capacity, but the current condition near the stream is not severe. According to expert evaluation, changes to the city center traffic pattern, new city center development, and especially the increasing number of cars no longer entering the city center assisted policies to make the city more oriented towards public transit. Due to the success of the removal of Cheonggye Overpass and transportation improvement plans, Seoul moved onto other overpasses. The city government paid extra attention to residents who consistently demanded removal because of the blighted cityscape and hindered regional development. Comprehensive plans were established, with the overpasses removed in phases. Table 1 provides a summary of this overpass removal in Seoul.

<Table 1> Overpass Removal (by Year)

|

Name

|

Built in

|

Removed in

|

Reason for Demolition

|

|

Samgakji Rotary Overpass

|

1967

|

Nov. 1994

|

Interference with subway (line 6) construction

|

|

Tteokjeon Overpass

|

1977

|

Feb. 2002

|

Deterioration, improvement of urban environment

|

|

Noryangjin Reserve Overpass

|

1969

|

Feb. 2003

|

Interference with subway (line 6) construction

|

|

Wonnam Overpass

|

1969

|

May 2003

|

Rearrangement of traffic system for the Cheonggye Stream Restoration project

|

|

Cheonggye Overpass

|

1969

|

Sep. 2003

|

Cheonggye Stream Restoration project

|

|

Samil Overpass

|

1970

|

Oct. 2003

|

Removal of the connecting Cheonggye Overpass

|

|

Miah Overpass

|

1978

|

Feb. 2004

|

Improvement of traffic flow, installation of center bus lane

|

|

Seoul Station Overpass

|

1970

|

Feb. 2004

|

Safety, beautification of the city

|

|

Hyehwa Overpass

|

1971

|

Aug. 2008

|

Isolated and cut-off center bus lane

|

|

Gwanghee Overpass

|

1967

|

Nov. 2008

|

Deterioration, improvement of traffic flow

|

|

Hoehyeon Overpass

|

1977

|

Sep. 2009

|

Interference with view of Nam Mountain, improvement of traffic flow

|

|

Hangang Bridge Overpass (North)

|

1968

|

Sep. 2009

|

Improvement of Han River view, disrupted traffic flow

|

|

Mullae Overpass

|

1979

|

Aug. 2010

|

Isolated and cut-off center bus lane, disrupted traffic flow

|

|

Hwayang Overpass

|

1979

|

Feb. 2011

|

Deterioration, disrupted traffic flow

|

|

Noryangjin Overpass

|

1981

|

Mar. 2011

|

Improvement of cityscape

|

|

Hongje Overpass

|

1977

|

Feb. 2012

|

Isolated and cut-off center bus lane, disrupted traffic flow

|

|

Ahyeon Overpass

|

1968

|

Mar. 2014

|

Isolated and cut-off center bus lane, disrupted traffic flow

|

|

Yaksu Overpass

|

1984

|

Jul. 2014

|

Beautification of the city

|

Removal Process

First, the City of Seoul identifies problems with traffic control and management that may arise from removal and comes up with solutions. Items to be reviewed are then determined (location and function of the intersection, traffic flow, maintenance costs, suitability with plans for surroundings, etc.) and evaluated to consider feasibility and priorities.

<Figure 2> The Removal Process.jpg)

| Identify target overpass | ||||

| Analyze conditions & surrounding environment | ||||

| Identify problems and their causes | ||||

| Come up with alternatives & conduct simulations | ||||

| Review transportation environment & alternatives | Review cityscape & regional development issues | Review plans for the surroundings | Review the level of deterioration & maintenance costs | Review issues in environmental and civil complaints |

| Finalize plans for improvement & make decisions on priorities | ||||

<Table 2> Items for Review Prior to Removal

|

Items

|

Review

|

|

|

Category

|

Subcategory

|

|

|

Transportation Environment & Alternatives

|

Location & Functional Characteristics

|

Review feasibility; consider connection with major roads and functional characteristics (gaps, traverse, street traffic).

|

|

Mobility & Accessibility

|

Consider effects of change in optimal plans before and after removal, such as congestion, speed, waiting line, etc.

|

|

|

Cityscape & Regional Development

|

Cityscape

|

Consider improvements to the cityscape and slum areas.

|

|

Regional Development

|

Consider the possibilities of development and revitalization of nearby areas.

|

|

|

Plans for Surroundings

|

Development Plans for Adjacent Land

|

Ensure balance with existing land use plans, and facilities and land development programs.

|

|

Adjacent Road Plans

|

Ensure balance with roads and railroads.

|

|

|

Deterioration & Maintenance Costs

|

Deterioration

|

Consider deterioration over time.

|

|

Maintenance Costs

|

Consider annual maintenance costs.

|

|

|

Environmental & Civil Complaints

|

Environment

|

Consider noise, air quality, etc.

|

|

Civil Complaints

|

Consider potential complaints related to overpass removal.

|

|

Examples of Removal & Consequent Measures

Removals in 2010 & 2011

In 2010 and 2011, the City of Seoul removed 6 overpasses deemed to have minor traffic impact. In 2010, the Hwayang, Noryangjin, and Mullae were removed; in 2011, the Ahyeon, Seodaemun, and Hongje – linked to the installation of center bus lanes – were demolished. Of these, the Hwayang, Noryangjin, and Mullae had been frequent subjects of complaints as their entry/exit points created bottlenecks and undermined regional development. Removal of these overpasses did not have any significant effect on adjacent roads but did improve the cityscape. In particular, the removal of the Mullae Overpass enhanced connection to the isolated center bus lane, making it easier for people to use public transit. The Ahyeon, Seodaemun, and Hongje Overpasses were removed in 2011 when the center bus lane was opened on the Shinchon-ro and Toingil-Euiju-ro road, materially improving the cityscape and regional development.

Major Preventive Measures

To mitigate congestion from the removal of the overpasses, the City of Seoul came up with various preventive measures, such as improving signal operation at adjacent intersections, securing additional lanes, enhancing connection of the center bus lane, and modifying bus routes. Details can be seen in Table 3 below.

<Table 3> Overpass Removal: Major Congestion-Prevention Measures

|

Demolished Overpass

|

Preventive Measures

|

|

Hwayang Overpass

|

Modified signal operations at adjacent intersections to facilitate linear traffic flow.

(From simultaneous straight/left signals to differently timed left signals) |

|

Noryangjin Overpass

|

Added extra straight/left-turn lanes.

|

|

Mullae Overpass

|

Improved connection to center bus lane; enhanced side lanes for cars making a U-turn where the overpass used to be; secured detour routes.

|

|

Ahyeon Overpass

|

Extended center bus lane after overpass removal; added extra left-turn lanes, and adjusted community bus routes.

|

|

Seodaemun Overpass

|

Removed double intersection, U-turns used.

|

|

Hongje Overpass

|

Removed left-turn lane, added detour bridge, improved side lanes, and secured detour routes to augment intersection capacity.

|

Major Achievements

Improved Traffic Flow

On many occasions, overpass removal improved traffic flow in the vicinity. Analysis of morning traffic flow before and after removal of Wonnam, Miah, and Hyehwa Overpasses shows that average speed increased in these areas except for the Hongje Overpass area. There was a tendency for a reduction in travel speed on roads immediately after the removal, but speed returned to normal levels or increased within a year or two. This improvement was due not only to overpass removal, but also i) physical changes (e.g., increased capacity of intersections due to expanded access; geometric improvement of intersections previously limited by overpass support columns; channelization of turn lanes); and ii) systemic changes (e.g., improvement of signal operations and route management; control of turns at intersections).

<Figure 3> Changes in Average Travel Speed after Overpass Removal.jpg)

Financial Effect: Greater Revenues for Adjacent Businesses & Increased Housing Prices

In many cases, housing prices go up when an overpass is removed. The City of Seoul compared officially-assessed land prices in the vicinity of the overpasses and found that the land prices increased faster near the removed overpass than in nearby regions. Figure 4 shows the official real estate prices in adjacent areas after removing 4 overpasses in Seoul; growth rate is high immediately before and after demolition. When the Tteokjeon Overpass was removed in 2002, prices of real estate in the surrounding area rose by 18% in 2003 and 2004 whereas the average growth rate in all of Dongdaemun-gu (where the overpass had been) was only 5.09% during the same period. Prices of land near the Miah Overpass, removed in 2004, rose by 16% in 2005 and 2006 – about 10% higher than the 6% growth rate of Seongbuk-gu and Gangbuk-gu.

<Figure 4> Changes in Real Estate Prices in Immediate Vicinities after Overpass Removal.jpg)

Note: Red circle denotes year overpass was removed.

Source: Internal data, Seoul Metropolitan Government.

Greater Value to the Surrounding Landscape

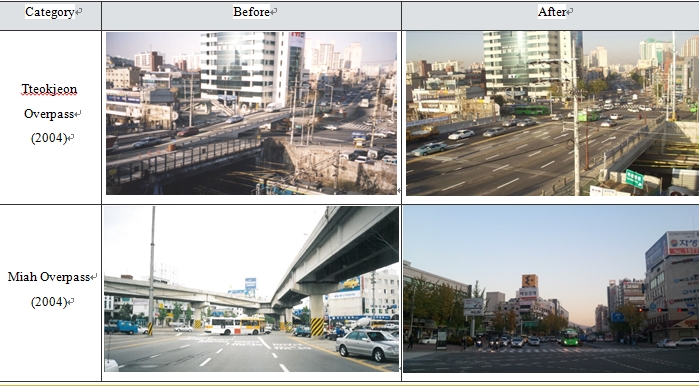

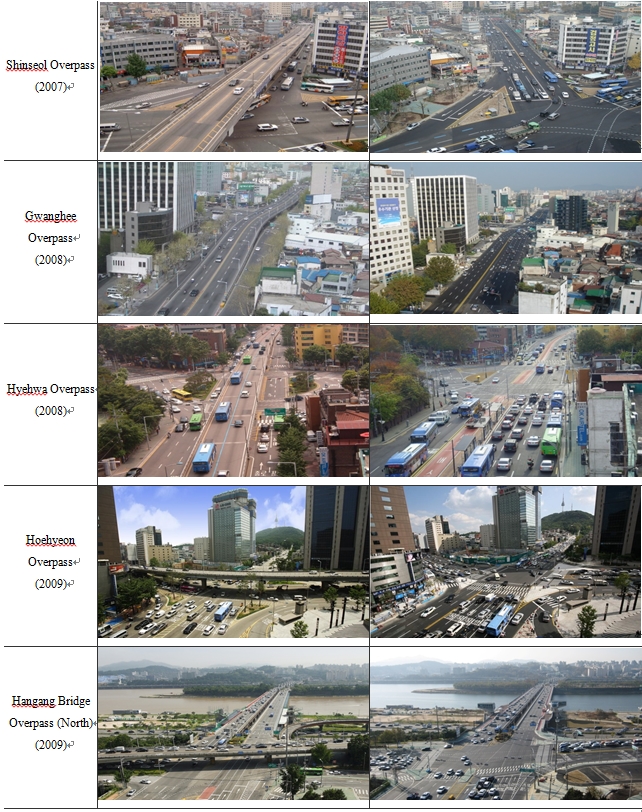

In terms of landscape, the view of the intersections is more open and sweeping after an overpass is removed, as seen in Figure 5. It is expected that people who enter the region are more satisfied with the view.

<Figure 5> Before and After Overpass Removal

Source: Internal data, Seoul Metropolitan Government.

Kim Jong-hyeok et al (2013) estimated that the removal of overpasses would lead to cityscape improvements and consequential benefits, which were calculated based on the contingent valuation method on the 11 overpasses that have been removed since 2002. The result showed that removing an overpass is worth KRW 6.3 – 13.3 billion annually; all told, the benefits from removing the 11 overpasses has been worth KRW 107.1 billion so far.

Limitations & Needed Improvements

Removing old overpasses that undermine the cityscape and regional development brings positive results to local residents and others passing through, but there are still experts and residents who believe that the removal is less ideal in terms of traffic flow, partly due to a lack of studies that clarify the socioeconomic effects of the removal. It is therefore necessary to continue monitoring and analyzing the effects, the results of which can be used later to set the course for future direction.

Indeed, removal is positive in many ways, such as traffic flow and cityscape, but resultant losses should not be ignored. As the paradigm of transportation policy continues to change to accommodate pedestrians and public transit, the removal of overpasses is a reasonable change that suits this paradigm shift, but cannot be an excuse for a “one-size-fits-all” approach: that demolition can resolve anything. Economic loss due to slower traffic may be as great as the benefits from boosted commerce and improved landscape. On the other hand, the High Line in Manhattan, New York shows an old overpass that has been transformed into an urban park, significantly increasing the value of nearby businesses and real estate, and has become one of the most visited tourist attractions in the city. At times, rehabilitation should be considered before demolition, as can be seen in this case from New York.

Experts who are concerned over demolition-oriented policies insist that the negative aspects of demolition should not be ignored. According to data from the City of Seoul, business arcades near the 5 removed overpasses had a 10% increase in revenue but underground arcades experienced a severe drop in their revenues. Previously, pedestrians had to go underground to cross the road, but after removal of the overpass, they could use the new crosswalk and rarely went underground. It is imperative that a balance should be struck between demolition and preservation (utilization), with keen consideration for the improvement of environments, businesses, and regional development.

References

Kim Jong-hyeok, Kim Jin-tae, Kim Hong-gil, Shin Bok-min, 2013, “Analytical Study on the Removal of Overpasses in Seoul & Consequent Benefits from the Improved Cityscape”, Seoul Studies, Volume 14, Issue 4.

Kim Jong-hyeok, Kim Hong-gil, 2011, “Before & After Overpass Removal in Seoul”, Road Transport #125.Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2012, “Comprehensive Report on Detailed Design for Demolition of Seodaemun & Ahyeon Overpasses”.